Stamping feat

Giannandrea Poesio

Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault Sadler's Wells Theatre

Eloot stamping is a common feature of

many forms of dance. This is not surprising because it provides immediate rhythmical accompaniment to the dance, while being integral to the dance action. Inspired by what many consider as the most natural and first man-made rhythmmaking in the world, illustrious choreographers have often drawn upon this primeval idea for their artistic creations. Footfalls, therefore, have often been extrapolated from their traditionally non-theatrical contexts and imported into ballets such as those by Maurice Bejart and Jiri Kylian, or into more radical theatre-dance works, such as Maguy Mann's memorable May B (1981).

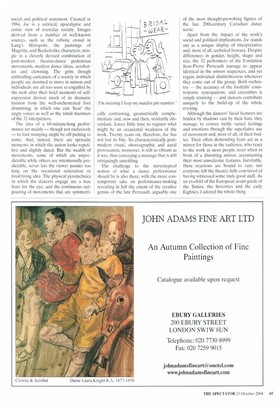

In Jean-Pierre Perreault's Joe, rhythmical patterns created by stamping, tapping, and shuffling feet underscore the 68minute-long action, thus compensating for the almost total lack of music. In this context, however, foot action is far more than mere accompaniment to the dance or one of its distinctive structural features. From the opening sequence, it is clear that foot drumming in Joe is intended to make a social and political statement. Created in 1984, foe is a satirical, apocalyptic and comic view of everyday society. Images derived from a number of well-known sources, such as the robotic crowd in Lang's Metropolis, the paintings of Magritte, and Beckett-like characters, mingle in a cleverly devised combination of post-modern theatre-dance pedestrian movements, modern dance ideas, acrobatics and clowning. The grim though enthralling caricature of a society in which people are doomed to move in unison and individuals are all too soon re-engulfed by the mob after their brief moments of selfexpression derives much of its dramatic tension from the well-orchestrated foot drumming, in which one can 'hear' the angry voices as well as the timid murmurs of the 32 interpreters.

The idea of a 68-minute-long performance set mainly — though not exclusively — to foot stamping might be off-putting to some. And, indeed, there are sporadic moments in which the action looks repetitive and slightly dated. But the wealth of movements, some of which are unpredictable while others are intentionally predictable, never lets the viewer ponder too long on the occasional reiteration or tired/tiring idea. The physical pyrotechnics in which the dancers engage are a true feast for the eye, and the continuous outpouring of movements that are symmetri

cally contrasting, geometrically complementary and, now and then, stridently discordant, leaves little time to register what might be an occasional weakness of the work. Twenty years on, therefore, Joe has not lost its bite. Its characteristically postmodern visual, choreographic and aural provocation, moreover, is still as vibrant as it was, thus conveying a message that is still intriguingly unsettling.

The challenge to the stereotypical notion of what a dance performance should be is also there, with the more contemporary take on performance-making revealing in full the extent of the creative genius of the late Perreault, arguably one of the most thought-provoking figures of the late 20th-century Canadian dance scene.

Apart from the impact of the work's social and political implications, Joe stands out as a unique display of interpretative and, most of all, technical bravura. Despite differences in gender, height, shape and sin, the 32 performers of the Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault manage to appear identical in the unison sequences, and yet regain individual distinctiveness whenever they come out of the group. Both orchestra — the accuracy of the footfalls' counterpoint, syncopations, and ensembles is simply stunning — and dancers contribute uniquely to the build-up of the whole evening.

Although the dancers' facial features are hidden by shadows cast by their hats, they manage to convey richly varied feelings and emotions through the superlative use of movement and, most of all, of their bodies. Their often demanding feats act as a mirror for those in the audience, who react to the work as most people react when in front of a distorting mirror, accentuating their most unwelcome features. Inevitably, these reactions are bound to vary; not everyone left the theatre fully convinced of having witnessed some truly good stuff, As an ex-child of the European avant-garde of the Sixties, the Seventies and the early Eighties, I adored the whole thing.

Previous page

Previous page