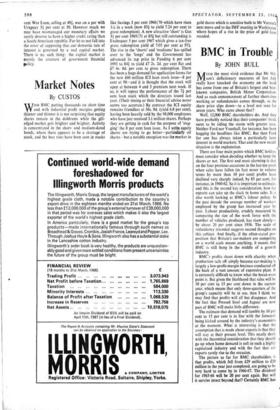

BMC in Trouble

By JOHN BULL

MUCH the most vivid evidence that Mr Wil- son's deflationary measures of last July really have knocked the economy on the head has come from one of Britain's largest and best- known companies, British Motor Corporation. And as each announcement of further short-time working or redundancies comes through, so the share price slips down—to a level not seen for seven years. Who cares about that?

Well, 12,000 BMC shareholders do. And they have probably noticed that their companies' rivals seem to be riding the storm with greater ease. Neither Ford nor Vauxhall, for instance, has been hogging the headlines like BMC. But then Ford for one has always taken a particularly keen interest in world markets. That and the new model situation is the explanation.

There are four main points which BMC holders must consider when deciding whether to keep the shares or not. The first and most alarming is that on the four previous occasions in the last ten years when sales have fallen (in fact never in volume terms by more than 10 per cent) profits have declined very sharply indeed, by 85 per cent, for instance, in 1960-62. So it is important to estimate, and this is the second key consideration, how far exports can take up the slack in home sales. It is also worth looking at BMC's labour policy. In the past decade the average number of workers employed by the group has increased year by year. Labour productivity, crudely measured by comparing the size of the work force with the number of vehicles produced, has risen slowly— by about 20 per cent since 1956. The scale of redundancy intended suggests second thoughts on this subject. And finally, if the often-stated pro- position that Britain's car-makers are competing on a world scale means anything, it means that BMC is still bang in the middle of a growth industry.

BMC's profits shoot down with alacrity when production tails off simply because car-making is largely a low-profit-margin business conducted off the back of a vast amount of expensive plant. It is extremely difficult to know what the break-even point is. But given the likelihood that sales will be 10 per cent to 15 per cent down in the current year, which means that only three-quarters of the group's capacity will be in use, then I think we may find that profits will all but disappear. And the fact that Pressed Steel and Jaguar are now part of BMC will make little difference.

The estimate that demand will tumble by 10 per cent to 15 per cent is in line-with the forecasts being kicked around by the industry's economists at the moment. What is interesting is that the assumption that is made about exports is that they will stay at their present level. This neatly deals with the theoretical consideration that they should go up when home demand is soft in such a highly capitalised industry and with the fact that car exports rarely rise to the occasion.

The picture so far for BMC shareholders is that profits, which fell from £29 million to £20 million in the year just completed, are going to be very hard to come by in 1966-67. The dividend for 1965-66 will be 20 per cent again. But will it survive intact beyond that? Certainly BMC has

a fine record for maintaining the payment to shareholders through thick and thin. There is a f4 million dividend reserve set aside for the hard years. On the other hand, dividends cost much more than they did in the last motor industry recession, thanks to the new tax laws. And the group has quite a load of capital expenditure to carry in the final years of the 1960s. So the divi- dend is not to be taken for granted, as the 9 per cent yield on the shares at Ils. shows. But I would not sell now. It is too late. Furthermore, there is the point about motor-car manufacture being a growth industry to consider.

But first, two subsidiary thoughts: it looks as if the opportunity is being taken to effect a once- and-for-all reduction in BMC's labour costs. Rough international comparisons demonstrate

that it is possible to produce as many cars as BMC does with significantly fewer men. And secondly, in the past twelve months or so, BMC has made two outstandingly cheap acquisitions, Pressed Steel and Jaguar. Eventually the benefits are going to come through into the profit and loss account.

Finally, although demand in the major Euro- pean economies may be sluggish at the moment and is in any case never likely to recover the buoyancy of the 1950s, potential in, say, Greece and Spain as far as Europe goes and in Africa, Asia and South America is enormous and well ahead of the present capacities of the European producers (exports from North America are tiny). This is why BMC will, in spite of every- thing, continue to enlarge its plant and facilities.

Previous page

Previous page