A history of the Spectator

Robert Blake

The Spectator was founded in 1828. It was not of course the first journal to bear the name, and no doubt there was a deliberate allusion to the famous organ of Addison and Steele in its baptism. The precise circumstances of its origin are somewhat obscure. The first editor was Robert Stephen Rintoul born in 1787 who had edited the Dundee Advertiser from 1811 to 1825. He made a success of it, converting the paper from being a mere summary of the news from the London dailies into one with a definite outlook and opinion, his political standpoint being that of a Liberal reformer. He attracted the notice and friendship of Douglas Kinnaird, banker and friend of Byron, and Joseph Hume, the radical Member for Aberdeen. For reasons unknown Rintoul moved to Edinburgh in 1825 and started a short-lived paper.

In 1826 he went to London where, thanks to the influence of Kinnaird, he became editor of a new weekly called the Atlas. For reasons almost as obscure as those which prompted him to leave Dundee, he soon gave up too after some sort of quarrel with its proprietors, claiming that he did so 'in consequence of attempts to vulgarize and betwaddle the Atlas — contrary of our compact'. Exactly what he meant is far from clear, but he evidently had the sympathy of his patron, for Kinnaird, Joseph Hume and others, subscribed enough capital to launch yet another weekly. It was christened the Spectator and it has had a continuous history from that day to this. Rintoul also had the sympathy of the Atlas's contributors. The Spectator was advertised in The Times of 11th July, 1828 as 'The New London Weekly Paper, by the original Editor and contributors of the Atlas'. Rintoul, who was a powerful character, evidently stipulated complete editorial control. At some stage he acquired proprietorship too. When he decided to retire thirty years later, he was in a position to sell the paper.

Rintoul's outlook, and therefore the Spectator's, was liberal-radical. On the great political issue dominating the first four years of his editorship, he was a strong supporter of Parliamentary reform and did all in his power to back the famous Act of 1832. The Bill was introduced on 1 March 1831 by Lord John Russell, and eleven days later the Spectator coined the celebrated slogan – 'The Bill, the whole Bill, and nothing but the Bill', When the House of Lords seemed likely to throw it out, Rintoul's wrath knew no bounds. 'Some of the worst men who have ever lived have been Peers. Look at the numbers that are known as patrons and professors of the animal and degrading pursuits'. But when the Bill went through Rintoul was quick to disclaim revolutionary tendencies. 'The Spectator is of the Conservative order. One leading feature will be bound to mark our proceedings – respect for the sanctity of property'.

As one would expect, the Spectator was thrown into a state of splenetic fury when William IV dismissed Melbourne in 1834 and sent for the Duke of Wellington pending Peel's return from Italy.

In the meantime we are to be under the Dictatorship of a Field Marshall whose political career proves him to be utterly destitute of political principle – whose military career affords ample evidence of this stern and remorseless temperament . . There cannot be an hour's confidence in these selfish soldiers and backstair earwiggers of the King.

Fortunately Melbourne was soon back but Rintoul, though delighted that the Tories were out, had little use for that easy-going figure and on one occasion he facetiously suggested various Yuletide games for Ministers, among them 'Hide and Seek' which 'might be rendered interesting in the Palace by the discovery of the noble Favourite cunningly concealed in the folds of the Royal petticoat'. But there was no pleasing Rintoul. Peel was the alternative to Melbourne and he got short shrift too. In an open letter to him by 'Nestor' his private life was admitted to be respectable but, 'it will require the rarest domestic felicity to console you for public contempt, and the greatest personal purity to balance the political prostitution to which you are abandoned. I pity you, Sir, from the bottom of my heart'.

This was in March 1835. Six years later the Spectator gave a qualified welcome to Peel's second premiership – no wonder some readers wanted to know where it stood politically – and in 1846 Rintoul cordially supported the repeal of the Corn Laws. Disraeli, its principal opponent, was described as 'that spoiled child of Parliamentary fashion', and a week later his speeches as 'the ideal of pert presumption'. When Peel died the Spectator pronounced a generous encomium. But at times one is inclined to think that retirement or death were the only ways to secure Rintoul's testy approval. The Russell Cabinet of 1846-52 'died of inanition'. The ensuing DerbyDisraeli government was 'a practical reductio ad absurdum of all we have been doing as a nation'. The Aberdeen Coalition, however, met with some approbation, and Gladstone's budget of 1853 was actually praised – the work of 'an exact reasoner, an honest politician, a warmhearted patriot'. Palmerston, who followed Aberdeen was, predictably, regarded as an adventurer profiting from a wartime crisis; as Beach Thomas points out in his centenary history the Spectator took the same view of Lloyd George sixty years later.

Rintoul wrote little himself, but impressed his personality so forcibly upon his staff and contributors that the whole paper seemed to bear his imprint. At first it ran at a loss of between £7,000 and £8,000 p.a., but he put up the price from ninepence to a shilling, and raised the circulation from under 1000 to 3500 by 1840– which made the paper pay and put it second only to John Bull among the weeklies. The Spectator was not in those days solely a journal of opinion ana comment. It also summarised the news of the week, so that subscribers could regard it as in some measure a substitute for a daily.

Apart from general support of the moderate radical side in politics, there was one specific issue on which Rintoul felt very strongly. There were plenty of people who favoured 'emigration' as a palliative for the problems summed up as the Condition of England Question. Rintoul and Gibon Wakefield, who became his intimate friend, were passionate supporters of 'colonisation' which was a different matter, involving sale of land by the Government at a fixed, uniform and sufficient price, use of the money to finance emigration, and the development of the colonies as selfgoverning communities. Rintoul gave Wakefield ample space to propagate these unorthodox views. The foundation of South Australia and New Zealand and the settlement of Canada after the Durham Report were at least in part due to the paper's continual advocacy.

The Spectator, then as now, did not confine itself to politics. It reviewed books, music, pictures and the theatre. In Rintoul's day it cannot be said to have displayed any striking percipience. The Spectator tended to look at all the arts as branches of morality. For example of La Traviata, 'We emphatically deny that opera representations of interesting prostitutes . . . are the properest or likely means of exciting the right kind of sympathy and practical encouragement towards fallen women'. The paper found that Jane Eyre had 'a low tone of behaviour', that in Wuthering Heights the incidents and persons are too coarse and disagreeable to be attractive' and that in Bleak House 'truth of nature and sobriety of thought are largely sacrificed to mannerism and point' (the Spectator con sistently ran down Dickens). On the other hand the 'admirable little fictions' by which Harriet Martineau parabolically conveyed lessons in political economy received high praise. However the Spectator was not the only organ to make contemporary judgements that read strangely today.

In 1858 Rintoul, who was seventy-one, decided to retire. He sold the paper to a Mr Scott for a lump sum plus an annuity. We do not know the figures, but it must have been a good bargain in one respect for the purchaser, since Rintoul died only four months later. Nothing is known of Scott, who remained proprietor for only three years, except that he did not make a success of his property. The Spectator was very much in the doldrums when he in his turn sold it in 1861 — fortunately to a person of energy and enterprise.

The new owner and editor was Meredith Townsend born in 1831. He had begun his journalistic career in India where he became at the early age of twenty-two proprietor, editor and principal contributor of The Friend of India. In 1859 ill health took him back to England. He bought the Spectator in 1861. Soon afterwards Walter Bagehot introduced him to his friend Richard Holt Hutton, a Unitarian minister manqué, and on a sudden impulse after one or two meetings Townsend suggested partnership, calling out when Hutton was half downstairs from the office, 'I say, have you got any money?' A singularly cordial relationship thus began, and, though Townsend retained ultimate control, the two joint editors and co-proprietors scarely ever differed.

Hutton, who was five years older, was a theologian and philosopher. He had met Bagehot when they were both at University College London, and he recalls that 'in the vehemence of our argument as to whether the so-called logical principle of identity (A is A) was entitled to rank as a "law of thought" or only a postulate of language', they walked up and down Regent Street for nearly two hours 'in the vain attempts to find Oxford Street'. It would be nice to think that similar arguments similarly engross the attention of the alumni of that great institution today. Hutton wrote in what now seems an opaque diffuse style, but his contemporaries knew what he was driving at, and Gladstone, with whom he was on close terms, went so far as to describe him as 'the first critic of the nineteenth century'. He also said of the Spectator that it was 'one of the few papers which are written in the fear and love of God'.

Townsend was more racy. His successor, St. Loe Strachey, considered that 'he was, in matter of style, the greatest leader-writer who has ever appeared in the English Press'. He was a romanticist and a dramatist. There was a touch of the theatrical in almost all his articles. He was a great believer in uncompromising generalisations, but he had the true art of readability by always supporting them with specific statements. He could even enliven demographic statistics by the observation (how, one wonders, did he know?), 'half the centenarians in the world are negroes'. Unlike Rintoul, the two co-editors per sonally wrote the greater part of their journal. If their styles were diverse, unity was preserved by their common ideology.

On at least three major political questions of their time the two editors took a very clear and definite stand. The first was for the North against the South in the American Civil War. This issue, on which even Gladstone was equivocal, divided British opinion more widely and bitterly than the Spanish Civil War in the Thirties or the Biafran War in the Sixties. Apart from the Daily News, the Spectator was the only organ of any importance to come out categorically from the start on the side of the Federalists. It caused fury and lost readers, but it backed a winner and in the end was more than recouped in terms of readership.

The second was the Eastern crisis of 1876-78. Large massacres by Turkish irregular troops of unarmed Bulgarian civilians created the sort of dilemma for British foreign policy, which in a far less lurid form faces the Western world in its dealings with South Africa today. Morality dictated the dismantling of a regime which, even more than that of the Neapolitan Bourbons, deserved Gladstone's famous description — 'the negation of God erected into a system of government'. Realpolitik, however, dictated the preservation of Turkey as a bulwark against Russian expansion — basically the issue which led to the Crimean War. Disraeli tried to solve the problem by pretending that the massacres had not occurred, and, when denial became impossible, that they were not as bad as they were made out to be. The Spectator would have none of this, and the leaders by Townsend and Hutton are among the most pungent that they ever wrote. The leading journal in this battle was the Daily News whose correspondent first secured reliable information about the atrocities, but the Spectator gave powerful support, and its onslaughts against Disraeli were devastating. 'The verdict of history' — if there really ever is such a thing — is on the side of those who denounced the Prime Minister for what was the least creditable episode in the whole of his public career.

The third was even more important and led to a fundamental realignment of the Spectator's political attitudes. This Was the question of Irish Home Rule which split the Liberal Party from top to bottom in 1886 and ushered in twenty years of almost unbroken Conservative or, rather, Unionist, ascendancy. In spite of Hutton's personal friendship with Gladstone, the two editors opposed the Bill from the start, and the Spectator became the leading weekly on the side of the Liberal Unionist party. As with the line that it took on the American Civil War, the paper soon picked up far more readers than it at first lost as the result of its new departure.

The Home Rule crisis coincided with the beginning of a change in the control of the paper. In 1886 one of the principal leader writers, H.H. Asquith (later Prime Minister), gave up as a result of his entry into active politics. John St. Loe Strachey, whose father Sir Edward, 3rd baronet and head of an old landed family, had frequently contributed to the Spectator, took Asquith's place. Later the same year Hutton retired, and Strachey, who now played an even more active part, was given to understand that he would be the ultimate proprietor. In 1887 Hutton died, and in the same year Townsend, though remaining a regular contributor, ceased to edit the paper. Strachey was now, like Rintoul, sole owner and editor, 'And he was more than that', to quote Beach Thomas. 'He was also general manager, chief leader-writer and an ardent reviewer'. He threw himself into these multifarious roles with immense energy and zest. During his reign the circulation more than doubled reaching its pre-war apogee with over 22,000 in 1903. Although he had valuable support from his secondin-command, Charles Graves, and although he enlisted a host of distinguished contributors, it is no exaggeration to say that Strachey was the Spectator. Under him it became the most influential of all the London weeklies before 1914.

Strachey's most important political decision occurred over the Tariff Reform controversy which broke out in 1903 with effects on the Unionists almost as disastrous as those of Home Rule on the Liberals. The Liberal Unionism which he in general supported did not in itself determine the line he was to take. The leadership of the party was deeply divided, Joseph Chamberlain being a passionate Tariff Reformer and the Duke of Devonshire a firm (he was not passionate about anything) Free Trader. Strachey, following the tradtion of Rintoul, vigorously opposed tariffs.

Both under the Townsend-Hutton dicumvirate and under Strachey, the Spectator's judgement in literary matters seems to have improved —or at any rate to accord more nearly with modern opinion. It reviewed Samuel Butler's Erewhon with enthusiasm in 1876, and in 1878 printed his famous Psalm of Montreal of which every verse ends with the words '0 God! 0 Montreal!' It was inspired by his discover)/ that the Discobolus had been concealed in the lumber room of the Montreal Museum in order that Canadian citizens should not be affronted by the sight of full frontal male nudity. It acclaimed Kipling when he was almost wholly unknown, and described — rightly — Doughty's Arabia Deserta as 'a great book'. It was generous to Pater, Moore, Stevenson and Hardy. Under both regimes the list of contributors is a roll call of the most famous figures in the intellectual and literary world of the day. The outbreak of war in 1914 had an unfavourable effect on the paper's fortunes. Strachey, by nature feverishly excitable, became more so than ever and plunged into his somewhat archaic military duties as High Sheriff of Surrey with a strenuous patriotism which was too much for him when added to his work as owner-editor. He was seriously ill and at one time his life was despaired of. He recovered, but the paper suffered both during and in the aftermath of war. It lost something of its identity and Strachey must have seemed a bit of a crank to many readers when he took up the cause of state control of the sale of liquor. Whatever the reason, circulation fell as low as 13,500 m 1922. That year Strachey asked Mr (later Sir) Evelyn Wrench to take over the business side. They had long had the common interest of improving Anglo-American relations — which greatly concerned Strachey during the war. By 1924 Wrench had brought the circulation up to 17,000. In 1925 Strachey retired and Wrench bought his controlling interest for £25,000 thus becoming like Rintoul, editor and proprietor. In 1926 the circulation rose to 21,500 — an improvement very similar to the change that had occurred when Strachey himself had taken over. The following year Strachey died at sixty-seven.

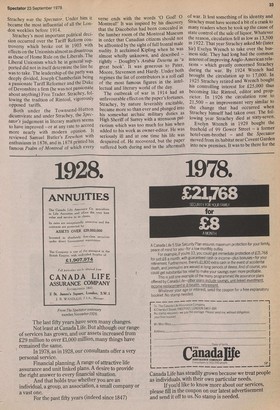

Evelyn Wrench in 1929 bought the freehold of 99 Gower Street — a former hotel-cum-brothel — and the Spectator moved from its habitat near Covent Garden into new premises. It was to be there for the next forty-six years. Wrench was not the only shareholder. Sir Angus Watson, .a business man from Newcastle, had a minority stake. He was a staunch teetotaler, and the Spectator carried no advertisements for drink while he had an interest in the paper. In October 1932 Wrench, who had many other irons in the fire, handed the editorship to J. Wilson Harris, a former leader writerin the Daily News and strong supporter of the League of Nations Union. He was to hold the post for just over twenty years and from 1945 to 1950 he was independent Member for Cambridge University. Under his regime the readership reached its peak figure, rising to 53,500 in 1946.

Harris was succeeded briefly by his assistant editor, Walter Taplin. In 1954 Sir Evelyn Wrench sold the paper to Mr (now Sir) Ian Gilmour who reverted to the old tradition and became editor-cum-proprietor. He enlivened the paper and injected a new element of irreverence, fun and controversy. Readers were shocked by the Spectator's opposition to 'Suez', it support of the rights of Palestinian Arabs and its campaign against capital punishment. People speculated on the identity of 'Taper' (Bernard Levin) who mercifully kept quiet about Wagner and-was extremely funny about politics. 'Sir Shortly Floorcross' and 'Sir Reginald Bullying Manner' were two of his most enjoyable inventions, but there were many others. In 1959 Ian Gilmour, who was considering entry into politics, gave up the editorship, though he remained proprietor for another eight years. Three years later in a by-election he became Conservative MP for Central Norfolk.

The new editor was Brian Inglis, who had previously been assistant editor, but after three years he went into the world of television, and was succeeded in 1962 by lain Hamilton whose tenure was even briefer; amidst a blaze of publicity and recrirnination Ian Gilmour replaced him at the end of 1963 by lain Macleod (the common Christian names of all three did not go unnoticed). This was certainly the most remarkable appointment in the history of the Spectator, indeed in the history of British journalism -the only example of a major figure moving from politics to an editorial chair. It has occurred the other way round though less abruptly Ian Gilmour himself and John Morley are examples but Macleod's transition remains unique. The tonservatives were still in office, though their prospects of surviving the next election looked very bad: the move was made possible because of Macleod's decision to resign from the Cabinet rather than serve under Lord Home who, as a result of an arcane process little understood by the general public, had succeeded Harold Macmillan in October. In retrospect one may wonder whether the Conservatives would have lost the close-fought election of 1964 if he had remained and given his support to the new Prime Minister.

Macleod remained editor for two years. He was in one sense an amateur, but he turned out to have a natural flair for journalism, and the paper, after a slightly dull period after the end of Ian Gilmour's editorship, became more lively. Macleod was himself responsible for what must be, with every credit to the contributions of Rintoul, Townsend, Hutton, Strachey, Wilson Harris and others, the most famous single piece that has yet appeared in the century and a half of the Spectator's existence. It came out in the number of January 17, 1964 under the heading of 'The Tory Leadership', and took the form of a lengthy review of a piece of instant history by Randolph Churchill entitled The Fight for the Tory Leadership. As a review it was a devastating broadside and the book was left by the end little better than a smoking hulk. 'Four -fifths of Churchill's book could have been compiled by anyone with a pair of scissors, a pot of paste and a built-in prejudice against Mr Butler and Sir William Haley'. etc. But the main interest of the article was its first hand account of the hitherto well-concealed details of a puzzling crisis of succession by one of the principal actors only three months after the event. There has been nothing quite like it in any journal before or since.

When Macleod returned in 1965 to active politics as a member of the Shadow Cabinet he was succeeded by Nigel Lawson who had previously been City Editor of the Sunday Telegraph and was Sir Alec Douglas-Home's personal assistant in the 1964 election. He is now Conservative MP for Blaby. Under him the Spectator became even more lively, and particularly strong on economics and finance. In that context no survey of the paper's modern history can omit a reference to its longest running columnist Nicholas Davenport, who has been writing his unorthodox and stimulating 'In the City' since 1953. One of the most entertaining features appearing during Nigel Lawson's editorship were the letters of 'Mercurius Oxoniensis', a pseudonym concealing not very sue cessfullythe identity of a famous Oxford historian. Written in the style of John Aubrey they satirized the follies of Oxford students and dons at a time when some of them (especially the former) were being Particularly foolish.

In 1967 Ian Gilmour at last parted with the paper. The purchaser was a youngish business man, Harry Creighton, who had no previous experience, but was keenly interested in journalism and politics. He was strongly opposed to the Common Market, and, when Lawson left in 1970 to fight (unsuccessfully as it happened) Eton and Slough in the general election, he appointed George Gale who had been a frequent contributor and shared the proprietor's opinions. It was perhaps natural that hostility towards the EEC should spill over into hostility towards its principal supporter, Edward Heath. Whether or not that was the reason, the Spectator became conspicuous among organs of opinion for its attacks on the Conservative leader; its rejoicing at his defeat early in 1975 by Margaret Thatcher was open and unabashed.

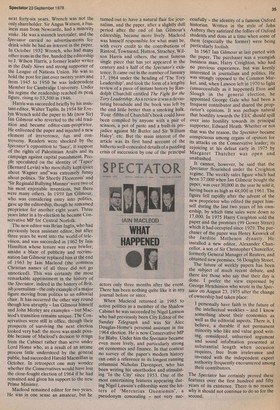

It cannot, however, be said that the Spectator flourished under the Creighton regime. The weekly sales figure which had been 37,000 when Ian Gilmour bought the paper, was over 30,000 in the year he sold it, having been as high as 48,000 in 1961. The figure fell rapidly after the advent of the new proprietor who edited the paper himself during the last two years of his ownership, by which time sales were down to 17,000. In 1975 Harry Creighton sold the paper and the premises (99 Gower Street) which it had occupied since 1929. The purchaser of the paper was Henry Keswick of the Jardine Matheson dynasty. He installed a new editor, Alexander Chancellor, a son of Sir Christopher Chancellor, formerly General Manager of Reuters, and obtained new premises, 56 Doughty Street.

The future of weekly papers has been the subject of much recent debate, and there are those who say that their day is done. I prefer the view expressed by George Hutchinson who wrote in the Spectator on August 23, 1975 after the change of ownership had taken place: I personally have faith in the future of the intellectual weeklies and I know something about their economics as well as the editorial aspects. There is, I believe, a durable if not permanent minority who like and value good writing, considered, unhurried argument and sound information presented at substantial length when occasion requires, free from irrelevance and invested with the independent expert authority frequently encountered among their contributors.

The Spectator has certainly proved these features over the first hundred and fifty years of its existence. There is no reason why it should not continue to do so for the second.

Previous page

Previous page