Gobble and chirp of an odd couple

Frances Partridge

LYDIA AND MAYNARD: LETTERS BETWEEN LYDIA LOPOKOVA AND MAYNARD KEYNES edited by Polly Hill and Richard Keynes Deutsch, £17.95, pp.367 Just as handwriting always expresses something of the writer's character, so a two-way correspondence of love-letters — something that was common in the happy days before the telephone displaced the post — can give a good idea of the relationship and portraits of the partici- pants. Of course, skill in self-expression is variable, but something is certain to emerge. Here we have two famous people: one a brilliant thinker, economist, writer and patron of the arts, who has been the subject of biographies and discussion, the other a ballerina of the Imperial Russian Ballet and later of Diaghilev's, whose talents by their very nature could only have been fully conveyed on television. Rather an unlikely couple, one might think, yet fall in love they did. In spite of a few of the usual ups and downs they became pas- sionately devoted, mutually appreciative and amused, and finally contracted a mar- riage that was conventionally happy and lasted until Maynard's death.

Everything about Keynes is interesting, for he was undoubtedly one of the cleverest and most influential men of this century. One thing that is well known is that during his early career at King's College, Cambridge he was a homosexual, along with many of the other outstanding men at King's at that time. Not exclusively, however: there is evidence of several fleet- ing affairs with young women (I can think of two), but none I believe which displayed anything like the constancy and warmth he lavished on Lydia. He saw her dancing in Diaghilev's company and was captivated like many others. He met her in person in October 1918 at a party at the Sitwells. During the busy years of his public life following the war, the feelings between the two seem to have grown and prospered, and by January 1922 he was writing to Vanessa Bell, 'The affair is very serious, and I don't in the least know what to do about it', to which Vanessa's somewhat characteristic reply was 'Don't marry her.'

The correspondence begins in the spring of 1922, but Maynard's first letters have not survived, and only by September 1923 do we have them in quantities to match hers. What sort of personality does Lydia reveal? One that was enchantingly spon- taneous, high-spirited, original, warmly good-natured — and as resilient as a rubber ball. She paints her own self- portrait in the idiosyncracy of her English, above all in the way she signs off her letters. Here are a few examples: 'I gobble you from head to foot'; 'Very tender and at the same time exotic kisses'; 'My spirits are alive and good-humoured and fountains of feeling for you'; 'I coo you with my cheeks'; send a chirp from under the left breast', and many more just as inventive.

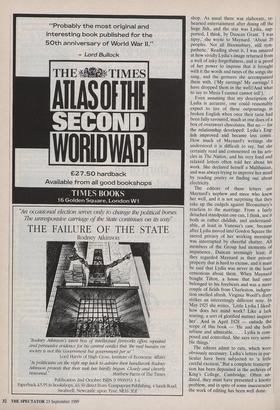

I was delighted to find in two of her letters references to an occasion when (aged 22) I met her for the first time and which was also my first experience of a Bloomsbury party. It took place in a Soho restaurant in January 1923, the excuse for it being that someone had spotted from the top of a bus a sturgeon in a fishmonger's shop. As usual there was elaborate, re- hearsed entertainment after dining off the huge fish, and the star was Lydia, sup- ported, I think, by Duncan Grant. 'I was tipsy,' she wrote to Maynard. 'About 20 peoples. Not all Bloomsbury, still sym- pathetic.' Reading about it, I was amazed at how vividly Lydia's image returned from a well of inky forgetfulness, and it is proof of her power to impress that it brought with it the words and tunes of the songs she sang, and the gestures she accompanied them with. (`My earrings! My earrings! have dropped them in the well!/And what to say to Mirza I cannot cannot tell').

Even assuming that my description of Lydia is accurate, one could reasonably expect to tire of these outpourings in broken English when once their taste had been fully savoured, much as one does of a box of oversweet chocolates. But no — for the relationship developed: Lydia's Eng- lish improved and became less comic. How much of Maynard's writings she understood it is difficult to say, but she certainly read and commented on his arti- cles in The Nation, and his very fond and relaxed letters often told her about his work. She declared herself a Malthusian, and was always trying to improve her mind by reading poetry or finding out about electricity.

The editors of these letters are Maynard's nephew and niece who knew her well, and it is not surprising that they take up the cudgels against Bloomsbury's reaction to the marriage. From a fairly detached standpoint one can, I think, see it both as rather childish, and understand- able, at least in Vanessa's case, because after Lydia moved into Gordon Square the sacred privacy of her working mornings was interrupted by cheerful chatter. All members of the Group had moments of impatience, Duncan seemingly least; if they regarded Maynard as their private property that is hard to excuse, and it must be said that Lydia was never in the least censorious about them. When Maynard bought Tilton, a house that had once belonged to his forebears and was a mere couple of fields from Charleston, indigna- tion swelled afresh. Virginia Woolf's diary strikes an interestingly different note. In May 1925 she writes, 'Little Lydia I liked: how does her mind work? Like a lark soaring; a sort of glorified instinct inspires her'. And in April 1928 — outside the scope of this book — `He and she both urbane and admirable. . . . Lydia is com- posed and controlled. She says very sensi- ble things.'

The editors admit to cuts, which were obviously necessary. Lydia's letters in par- ticular have been subjected to `a little careful excision.' But a complete transcrip- tion has been deposited in the archives of King's College, Cambridge. Often un- dated, they must have presented a knotty problem, and in spite of some inaccuracies the work of editing has been well done.

Previous page

Previous page