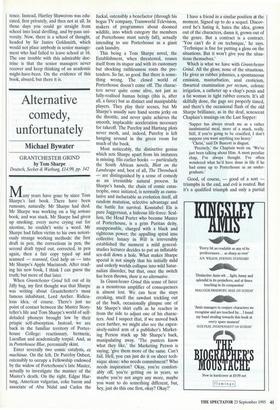

Alternative comedy, unfortunately

Michael Bywater

GRANTCHESTER GRIND

by Tom Sharpe

Deutsch, Secker & Warburg, £14.99, pp. 342 Many years have gone by since Tom Sharpe's last book. There have been rumours, naturally. Mr Sharpe had died. Mr Sharpe was working on a big serious book, and was stuck. Mr Sharpe had given up smoking; every nerve crying out for nicotine, he couldn't write a word. Mr Sharpe had fallen victim to his own notori- ously strange working methods: the first draft in pen, the corrections in pen, the second draft typed out, corrected, in pen again, then a fair copy typed up and scanned — scanned, God help us — into Mr Sharpe's Apple Macintosh. After read- ing his new book, I think I can guess the truth; but more of that later.

When Grantchester Grind fell out of its Jiffy bag, my first thought was that Sharpe was writing about Grantchester's most famous inhabitant, Lord Archer. Ridicu- lous idea, of course. There's just no point of contact between the Master Story- teller's life and Tom Sharpe's world of self- deluded phoneys brought low by their priapic self-absorption. Instead, we are back in the familiar territory of Porter- house College: reactionary, hermetic, Lucullan and academically torpid. And, as in Porterhouse Blue, perennially skint.

Enter severally two comic catalysts, ex machinae. On the left, Dr Purefoy Osbert, ostensibly to occupy a Fellowship endowed by the widow of Porterhouse's late Master, actually to investigate the manner of the Master's death. On the right, Edgar Har- tang, American vulgarian, coke baron and associate of Abu Nidal and Carlos the Jackal, ostensibly a benefactor (through his bogus TV company, Transworld Television, makers of programmes about doomed wildlife, into which category the members of Porterhouse must surely fall), actually intending to use Porterhouse as a giant cash laundry.

This being a Tom Sharpe novel, the Establishment, when threatened, rouses itself from its stupor and with its customary but shocking ruthlessness routs the pre- tenders. So far, so good. But there is some- thing wrong. The closed world of Porterhouse doesn't come off. The charac- ters never quite come alive, not just as fully-realised human beings (this is, after all, a farce) but as distinct and manipulable players. They play their scenes, but Mr Sharpe's usually sure hand seems jerky on the throttle, and never quite achieves the smooth, implacable acceleration necessary for takeoff. The Purefoy and Hartang plots never mesh, and, indeed, Purefoy is left hanging around in the green room for much of the book.

Most noticeably, the distinctive genius which sets Sharpe apart from his imitators is missing. His earlier books — particularly the South African novels, Blott on the Landscape and, best of all, The Throwback are distinguished by a sense of comedy as an irresistible natural process. In Sharpe's hands, the chain of comic catas- trophe, once initiated, is normally as cumu- lative and ineluctable as evolution itself, all random mutation, selective advantage and the battle for survival. Konstabel Els is pure Juggernaut, a hideous life-force: Scul- lion, the Head Porter who became Master of Porterhouse, is a grim Puritan deity, unappeasable, charged with a black and righteous power; the appalling spiral into collective lunacy in Wilt is irreversibly established the moment a mild general- studies lecturer decides to put an inflatable sex-doll down a hole. What makes Sharpe special is not simply that his initially mild and orderly worlds collapse into wild Satur- nalian disorder, but that, once the switch has been thrown, there is no alternative.

In Grantchester Grind this sense of farce as a monstrous amplifier of consequences is almost lost. We can hear the stays creaking, smell the sawdust trickling out of the back, occasionally glimpse one of Mr Sharpe's shirt cuffs as he reaches in from the side to adjust one of his charac- ters. And I suspect that, if we moved back even further, we might also see the expen- sively-suited arm of a publisher's Market- ing Person stuck up Mr Sharpe's back, manipulating away. 'The punters know what they like,' the Marketing Person is saying; 'give them more of the same. Can't fail. Hell, you can just do it on sheer tech- nique alone: who needs commitment? Who needs inspiration? Okay, you're comfort- ably off, you're getting on in years, so maybe you're not angry any more, maybe you want to do something different, but, hey, just do this one first, okay? Okay?' I have a friend in a similar position ai the moment. Signed up to do a sequel. Discov- ered he's hating it, hates the idea, grown out of the characters, damn it, grown out of the genre. But a contract is a contract. `You can't do it on technique,' he says. 'Technique is fine for putting a gloss on the situations. But it won't give you the situa- tions themselves.'

Which is what we have with Grantchester Grind. All the gloss; none of the situations. He gives us rubber johnnies, a spontaneous emission, masturbation, anal eroticism, thwarted examination per rectum, colonic irrigation, a catheter up a chap's penis and a fat woman in tight rubber corsets. It's all skilfully done, the gags are properly timed, and there's the occasional flash of the old Sharpe brilliance, as in the deaf, senescent Chaplain's musings on the Last Supper:

'Supper has always struck me as a rather insubstantial meal, more of a snack, really. Still, if you're going to be crucified, I don't suppose you want anything too heavy.' 'Christ,' said Dr Buscott in disgust. 'Precisely,' the Chaplain went on. 'We've just been talking about Him. A most peculiar chap, I've always thought. I've often wondered what he'd have done in life if he had come up to Porterhouse as an under- graduate.'

Good, of course, — good of a sort triumphs in the end, and evil is routed. But it's a qualified triumph and only a partial rout, to wrap up a virtuoso parading of inconsequentialities: P. G. Wodehouse meets Gilbert and George. Perhaps there's a Ph.D. here for some postgraduate at one of our exciting new 'universities': The Tool of Dionysus: The Role of the Penis as Agent of Catastrophe in the Novels of Tom Sharpe. But there comes a time when even the mightiest swordsman has to retire his trusty Holofernes to honourable quiescence. Mr Sharpe has done his bit. He has fulfilled his contract. We have much to thank him for. I suggest the Marketing People now let the man write what he wants to write.

Previous page

Previous page