A STUPID WAR'

Boris Johnson talks to the Colombian

Ambassador about the US defoliant that destroys coca — and all other crops

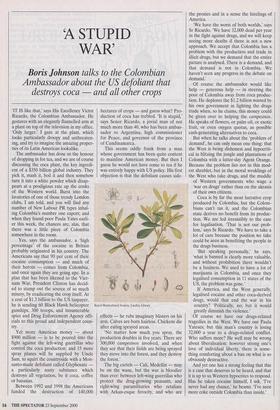

`IT IS like that,' says His Excellency Victor Ricardo, the Colombian Ambassador. He gestures with an elegantly flannelled arm at a plant on top of the television in my office. `Only larger.' I gaze at the plant, which looks particularly droopy and unthreaten- ing, and try to imagine the amazing proper- ties of its Latin American lookalike.

The ambassador has done us the honour of dropping in for tea, and we are of course discussing the coca plant, the key ingredi- ent of a $350 billion global industry. They pick it, mash it, boil it and then somehow turn it into a white powder which disap- pears at a prodigious rate up the conks of the Western world. Burst into the lavatories of one of those trendy London clubs, I am told, and you will find any number of New Labour PR types inhal- ing Colombia's number one export; and when they found poor Paula Yates earli- er this week, the chances are, alas, that there was a little piece of Colombia somewhere in the room.

Yes, says the ambassador, a 'high percentage' of the cocaine in Britain probably originated in his country. The Americans say that 90 per cent of their cocaine consumption — and much of their heroin — comes from Colombia, and once again they are going ape. In a plan that has been likened to the Viet- nam War, President Clinton has decid- ed to stamp out the source of so much misery, by eradicating the crop itself. At a cost of $1.3 billion to the US taxpayer, he is sending 60 Black Hawk helicopter gunships, 300 troops, and innumerable spies and Drug Enforcement Agency offi- cials to this proud and independent coun- try.

Yet more American money — about $900 million — is to be poured into the fight against the left-wing guerrillas who control the coca production; and 15 more spray planes will be supplied by Uncle Sam, to squirt the countryside with a Mon- santo-made defoliant called Glyphosate a particularly nasty substance which destroys all vegetation, be it coca, coffee or bananas.

Between 1992 and 1998 the Americans funded the destruction of 140,000 hectares of crops — and guess what? Pro- duction of coca has trebled. 'It is stupid,' says Senor Ricardo, a jovial man of not much more than 40, who has been ambas- sador to Argentina, high commissioner for Peace, and governor of the province of Cundinamarca.

This seems oddly frank from a man whose government has been quite content to mainline American money. But then I guess he would not have come to tea if he was entirely happy with US policy. His first objection is that the defoliant causes side-

Royal Horticultural Society, Lindley Library

effects — he rubs imaginary blisters on his arm. Calves are born hairless. Chickens die after eating sprayed areas.

`No matter how much you spray, the production doubles in five years. There are 300,000 campesinos involved, and when they see that their fields are being sprayed they move into the forest, and they destroy the forest.'

The big cartels — Cali, Medellin — may be on the wane, but the war is bloodier than ever: between left-wing guerrillas who protect the drug-growing peasants, and right-wing paramilitaries who retaliate with Arkan-esque ferocity, and who are the proxies and in a sense the hirelings of America.

`We have the worst of both worlds,' says Sr Ricardo. 'We have 32,000 dead per year in the fight against drugs, and we will keep seeing more deaths if there is not a new approach. We accept that Colombia has a problem with the production and trade in illicit drugs, but we demand that the entire picture is analysed. There is a demand, and that demand is not in Colombia. We haven't seen any progress in the debate on demand.'

Of course the ambassador would like help — generous help — in steering the poor of Colombia away from coca produc- tion. He deplores the $1.2 billion wasted by his own government in fighting the drugs trade when, so he claims, this money could be given over to helping the campesinos. He speaks of flowers, or palm oil, or exotic fruit, or even oxygen quotas, as possible cash-generating alternatives to coca.

But when he talks about the 'problem of demand', he can only mean one thing: that the West is being dishonest and hypocriti- cal in blitzing the jungle and plantations of Colombia with a latter-day Agent Orange. Because the problem lies not in this mod- est shrublet, but in the moral weaklings of the West who take drugs, and the muddle of Western governments who wage a `war on drugs' rather than on the akrasia of their own citizens.

Coca is by far the most lucrative crop produced by Colombia, but the Colom- bians can't tax it, and the Colombian state derives no benefit from its produc- tion. We are led irresistibly to the case for legalisation. 'That is not our prob- lem,' says Sr Ricardo. 'We have to take a lot of care because the position we take could be seen as benefiting the people in the drugs business.

`But speaking personally,' he says, `what is banned is clearly more valuable, and without prohibition there wouldn't be a business. We used to have a lot of marijuana in Colombia, and once they legalised consumption in. 11 states of the US, the problem was gone.'

If America, and the West generally, legalised cocaine and other coca-derived drugs, would that end the war in his country? 'Politically, no; but it would greatly diminish the violence.'

Of course we have our drugs-related tragedies in the West. We have our Paula Yateses; but this man's country is losing 32,000 a year to a drugs-related conflict. Who suffers more? He well may be wrong about liberalisation: however strong one's love of individual liberty, there is some- thing comforting about a ban on what is so obviously destructive.

And yet one has a strong feeling that this is a case that deserves to be heard, and that it is up to us Western hypocrites to respond. Has he taken cocaine himself, I ask. Tye never had any chance,' he beams. 'I've seen more coke outside Colombia than inside.'

Previous page

Previous page