Required Reading

Mits. Leavis's book was required reading in my student days, along with the scrutineering of `F.R.L.' (its dedicatee), the works of I. A. Richards, Seven Types of Ambiguity, Culture and Environment, and How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth? Devouring Fiction and the Reading Public once more—it is definitely a work to devour—I am shamefully aware of a falling- off in my literary standards since the days when Cambridge astringently, not to say puritanically, set them for me. I enjoy Dickens and Kipling and Samuel Butler, and I'm fed up with George Sturt. Mea culpa. Mrs. Leavis is still right about most things, even though the general public has outgrown best-sellers like Sorrell and Son (. . 'There were still things he did and did not do, He was a gentleman'). Nor, I think, would a contemporary popular novelist be proud of not being 'a long-haired literary cove' and laud Murray's as being run by 'sportsmen and gentle- men and jolly good businessmen as well.' Other things have changed since 1932 (there's been the paperback revolution; public taste prefers violence to slop), but serious novelists still sell only 3,000 in hardbacks and journalists continue to debase English prose.

Mrs. Leavis's account of the decay of taste since the death of two traditions—the agrarian and the Puritan—is as fresh and disturbing as when it was first written, though few of us now would talk of the glories of the folk-life, all natural rhythms and Bible and salty proverbs. But the fact remains that Nashe and Deloney wrote better than Marjorie Proops, that popular

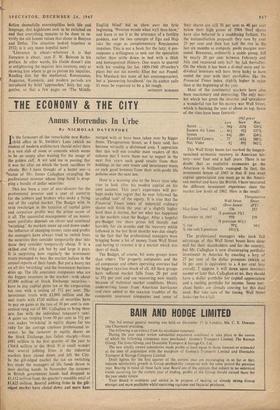

fiction shamefully oversimplifies both life and language, that highbrows seek to be switched on and that everything remains to be done to re- vivify the old honest values that shone in Bunyan and Defoe. The situation looked hopeless in 1932; is it any more hopeful now?

'Literature is about—whatever it is that literature is about,' says F. W. Bateson in his preface. In other words, his Guide doesn't aim at enlightening the inquirer into essences, only at showing him where to go to pursue his inquiries. Reading lists for the mediaeval, Renaissance, Augustan, Romantic, and modern periods are introduced by brief 'approaches,' bitty but sug- gestive, so that a few pages on 'The Middle English Mind' bid us chew over the lyric beginning, 'Westron wynde when wyll thou blow,' and learn to see it as the utterance of a fertility goddess, and the two concepts of. Ego and Hap take the stage as complementary Renaissance impulses. This is not a book for the lazy; it pre- supposes a willingness to seek out the specialists rather than settle down in bed with a thick and homogenised History. One wants to quarrel with his reading list for 1800-1960 (Priestley's plays but not his novels; Eliot but not Pound; Iris Murdoch but none of her contemporaries), but a 'pioneering handbook' (so its author calls it) must be expected to be a bit rough.

ANTHONY BURGESS

Previous page

Previous page