UNHOLY CITY: NEW JERUSALEM

Gavin Stamp surveys

the sad state of the most sacred city

THE DEVIL may not always have the best tunes but in Jerusalem the Muslims cer- tainly have the best architecture. The famous view of the ancient walled city from the east, from the top of the Mount of Olives, is dominated by the Dome of the Rock, the third most holy site for Islam, built by the Caliph 'Abd al-Malik at the end of the seventh century. Its pure octa- gonal form is clothed in gorgeous faience tiling while the present dome of gilded aluminium — a rather vulgar product of King Hussein's restoration of the 1950s — glows in the sun. The Dome stands proudly and in isolation on the Haram al-Sharif, the 'Noble Sanctuary', a raised plateau where once stood the Temple of Solomon and it is, along with the nearby al-Aqsa Mosque, a supreme expression of the clear, precise, rigid nature of Islam.

For C. R. Ashbee, the Arts & Crafts architect who was civic adviser to the British military and civilian administration in Jerusalem from 1918 to 1922, the Dome 'represents and draws into its heart the three religious traditions, Moslem, Christ- ian, Jew. Yet in a way it transmutes and transcends them all. Perhaps that was overdoing it, but it is still true that the Dome is the great symbol of Jerusalem, as is shown by the covers of guides and picture books, whether Israeli or Gentile. And compared with the spacious order of the present state of the Temple Mount, the places of worship of the two other great historical religions are not immediately impressive.

Below the Haram and contained by the city walls — Roman, Mameluke, Turkish — Jerusalem is a dense, tight network of narrow streets based on a Roman plan. The architecture is introverted, tucked away. It had to be: the domestic tradition here was an intelligent response to com- munal conflict: Jew, Christian and Mohammedan could withdraw into their own distinct quarters. By day, the main streets leading from the Damascus Gate are almost impassable, thronged with the crowds, bustle and noise of the Orient. But today, because of the inttfada, the shutters go up after noon and at night the Old City is like a ghost town or an Expressionist film set: dimly lit soukhs echo with the sound of The new colonnade before the Western Wall one's footsteps but all that move in the shadows are some of Jerusalem's many cats. Yet, behind closed doors, thousands of Palestinians live, and wait ....

Towers and campaniles on the skyline mark the presence of Christian churches, yet they are hard to find. The Holy Sepulchre itself is almost hidden until you emerge into a small square with the Gothic arcade of the Crusaders on one side. This place should be the holiest spot in Christ- endom yet many visitors are disappointed, perhaps because Christianity here is so dark, grimy and Oriental, with every space festooned with hanging lamps outdoing any Turkish mosque; perhaps because of the touting guides. 'I've never felt so pagan and repelled in my life,' wrote Ashbee. 'To come back to this mediaevalism after the quiet reverence and sanity of Islam ... is something like a shock.'

My own disappointment was that the church was full of scaffolding and the tiny Holy Sepulchre itself — that is, the Greek reconstruction of 1810 after a fire — is strapped together with girders. The restor- ers and the archaeologists have been at work, picking things clean and somehow sanitising what must have been wonderful- ly chaotic and neglected. Yet the old spirit survives. Fifteen lamps burn at the Holy Sepulchre — with dozens and dozens more hanging outside — five for the Orthodox, five for the Latins, four for the Armenians and one for the Copts. These precise numbers are important, and two other communities have rights in different parts of the church under the status quo estab- lished by the Turks: the Syrians and the Ethiopians.

Jerusalem is not a good advertisement for ecumenism. The city rather exemplifies the oldest of Christian traditions: sectar- ianism. A poignant illustration of this is the elevated position of the Ethiopians who, because at one stage they could not pay up, were exiled to the roof. Little houses sit up there with the dome of St Helena's Chapel rising through the courtyard. But there have been some changes. My Murray of 1903 notes how on entering the church, 'the first object that strikes our eye is a Turkish divan to the left on which recline Moslem officers and soldiers, sipping cof- fee and smoking narghiles. They are sta- tioned here to prevent the priests and votaries of the different Christian sects from open strife and bloodshed — a precaution which experience has proved to be only too necessary.'

At least those soldiers have gone — but there is still a strong military presence in Jerusalem today: teenage soldiers, boys and girls, all armed, lounging about out- side the City gates, or sitting high on the walls, guns at the ready. But they are there not to stop Christians fighting each other but to keep the Arabs from the Jews. For Jerusalem is a divided city and, for most of its inhabitants, the old city is a city under military occupation.

In 1948 the cease-fire line cut Jerusalem in half. To the west, in Israeli territory, were the suburbs which had sprung up beyond the city walls after the beginning of large-scale Jewish immigration in the late 19th century. Here are the shops along the Jaffa Road, the garden suburbs planned in the 1920s by German architects, the museums and institutional buildings and most of the luxury hotels. But the old city, and the area immediately to the north, remained in Jordanian hands. Following the war of 1967, Jerusalem was, in theory, unified but the division remains. The chanting of three shabby Armenians celeb- rating mass on their little patch in the north transept and with organ music wafting in Green Line is still evident both visually and socially: visually because of the clearance of property and partial dereliction, socially because there has been little movement across the line. East Jerusalem remains Arab — whether Christian or Muslim.

I was staying at St George's Cathedral Hostel which, being Anglican, is of course Gothic collegiate in style. This agreeable and admirable institution is north of the old city near the American Colony Hotel and where, until 1967, was sited the Mandelbaum Gate; that is, it is in East Jerusalem. For many Israelis it might as well have been on the moon for all they knew of it. A Jewish taxi driver told me it was 'not good' to be there; the wife of an Israeli architect in her house only a mile away asked me in all seriousness if it was not dangerous to stay in such a place. Of course there are good reasons for such fears, and it is true that many North Londoners do not know South London and vice versa, while suburban Americans sel- dom venture down town. But there is a strong feeling of paranoia in Jerusalem and the fact that many of its Jewish inhabitants do not dare go to its ancient heart shows that the would-be capital of Israel is not a happy place and that its unity is an admi- nistrative fiction.

It is difficult to see how unity is to be achieved in the present political climate. Both Jews and Arabs have every legitimate historical reason for being in Jerusalem; neither is going to leave. In defiance of international non-recognition of Jerusalem as the capital, the Israelis have built the ICnesset in West Jerusalem and have now embarked on the construction of a new Supreme Court nearby — replacing a converted building in the old Russian Compound. And the determination of the Arabs to stay is shown by the self- sacrificing intensity of the inufada. So the Israeli answer would seem to be encircle- ment. Beyond Arab East Jerusalem, new buildings are springing up.

These do not improve the city. The celebrated western prospect from the Mount of Olives has long been spoiled by the assertive towers of such as the Hilton and the King Solomon Hotel which do infinitely more damage than the pre-war accents of the campanile of the YMCA and the bulk of the King David. Now the view eastwards is diminished by new structures crawling up the slopes of Mount Scopus and the Mount of Olives. Not that these are towers; the two chief culprits, the Hyatt Hotel and the Mormon University — both by the same architect — attempt to be vaguely discreet by being low and broken up in bulk, but the impression is nevertheless one of intrusive vulgarity. But — as with everything in this divided city — the justice, or injustice, is not all on one side. The first great crime in the east was committed by the Jordanians when the Intercontinental was allowed to rise on the top of the Mount of Olives immediately above the Tombs of the Prophets and the Old Jewish Cemetery. This is a most special place for Jews as it is so convenient- ly sited for the Last Judgment, when the Messiah will enter the Temple Mount through the Golden Gate below. And, to add injury to insult, the stone graves which cover the hillside were desecrated, and many used as building material.

Stones, stones, stones. Everything in Jerusalem is built of stone — still, thanks to a regulation dating from the British Mandate. In the centre of the Dome of the Rock is the living rock itself on which Abraham almost slaughtered Isaac and from which Mohammed rose to Heaven. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is in part carved out of rock and the original Holy Sepulchre itself in the centre of the Rotunda was believed by Constantine to be the tomb of Joseph of Arimathaea and subsequently made into a little building by levelling the rock all around. And up stairs to the north of the nave is Calvary, a chapel in which the holes in the rock on which the three crucifixes stood are visible (only my good old Murray points out the anomaly that this summit of rock now hangs in space, for immediately below are more chapels — the answer may be that St Helena quarried out the rock below and took it back to Rome). As for the Jews, they worship at the Wailing Wall, properly the Western Wall of the Temple Mount, whose lowest courses of huge limestone blocks were laid by Herod the Great.

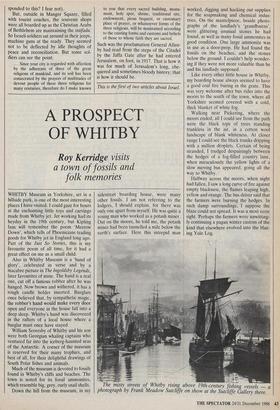

The Wailing Wall, the holiest site in Jewry, symbol of exile and diaspora, was once in a small open space surrounded by houses built right up to the great retaining wall. That must have been rather pictures- que. But after the Six-Day War, when the Wall was recaptured for Israel, the houses of the old Moroccan quarter were cleared away and a huge square created. This space, it must be said, is amorphous and ugly. In the last year an intelligent attempt has been made to give it some architectural coherence by building a long entrance colonnade on the south side through which visitors coming from the southern, Dung Gate pass. It is one of the few successful pieces of modern architecture in Old Jeru- salem.

Here, of course, is one part of the old city which Jews are happy to enter, for there is not only the Wailing Wall but also the Old Jewish Quarter within the walls. This south-eastern quadrant of the city was the scene of heavy fighting in 1948. The Jewish inhabitants were then driven out but it has been repopulated since 1967. But when it was recovered, the area was found to be badly damaged and partially des- troyed. It has been rebuilt, but not in the manner of, say, Warsaw. New blocks of housing have been erected, stone-faced but in a picturesque, Brutalist manner, which attempt to recreate the character of the old quarter without being reconstructions. As the lines of old narrow alleys are retained and as the levels drop dramatically down to the Western Wall, the result is not unsuc- cessful. But this area does not feel like the rest of Old Jerusalem. The shops are modern and expensive; the open spaces filled with those ubiquitous globe lamp- posts that characterise new shopping pre- cincts from Chester to Munich.

Elsewhere, the old city has been careful- ly treated and restored under the inspira- tion of Jerusalem's celebrated mayor, Ted- dy Kollek, who believes that, 'Jerusalem is no museum.' The streets have been re- paved, the tops of the walls opened to the public and open spaces preserved beyond. To a remarkable extent this continues the work begun by Ashbee and the Pro- Jerusalem Society in 1918. Ashbee, who planned a Ramparts Walk and parks out- side the walls, was an ideal person to interpret that reverence for Jerusalem which was the dominant architectural atti- tude of the British Mandate. But he became increasingly worried by the inter- nal contradictions within British policies towards Arab and Jew which were already encouraging communal strife. Although partly Jewish himself, he was alarmed by the arrogant and exclusive claims of Zion- ism. He left, disillusioned, in 1922.

It was Ashbee who, in 1918, helped overcome sectarian jealousy between Latins and Greeks and took down the wall that the Greeks had erected between the nave and chancel of the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem. This great church, the most convincing of all the sacred Christian sites in Palestine, lies some five miles south of Jerusalem, past the makeshift military fort that marks the crossing into the occupied West Bank. The not so little town of Bethlehem is unpre- possessing, as is the exterior of the church. Just one tiny door leads into the glorious nave: a simple, grand basilica built by Justinian on the site of the church raised under Constantine above yet another rock cave: the Chapel of the Nativity. Four great rows of Corinthian columns march towards the iconostasis and the garlands of hanging lamps in the Greek choir. It is good to know that the fourth column on the right was later painted with an image of our own King Canute and that lead for the restoration of 1480 came from Edward IV.

When I arrived, I had the church almost to myself and so was selfishly annoyed when it was invaded by coachloads of German tourists. I should not have been: even tourists may be pilgrims. As some of them stood in the Cave of the Nativity, in front of the silver star on the ground given by the Sultan to mark the birthplace of Our Lord, they spontaneously began to sing Salle Nacht. The effect, combined with the from the Catholic church of St Catherine beyond, was ineffably beautiful and poig- nant. (Would British tourists have re-

sponded to this? I fear not).

But, outside in Manger Square, filled with tourist coaches, the souvenir shops were all boarded up as the Christian Arabs of Bethlehem are maintaining the intifada. So Israeli soldiers sat around in their jeeps, machine guns at the ready. They seemed not to be deflected by idle thoughts of peace and reconciliation. But some sol- diers can see the point.

... Since your city is regarded with affection by the adherents of three of the great religions of mankind, and its soil has been consecrated by the prayers of multitudes of devout people of these three religions for many centuries, therefore do I make known

to you that every sacred building, monu- ment, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer, or whatsoever forms of the three religions, will be maintained according to the existing forms and customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred.

Such was the proclamation General Allen- by had read from the steps of the Citadel by the Jaffa Gate after he had entered Jerusalem, on foot, in 1917. That is how it was for much of Jerusalem's long, che- quered and sometimes bloody history; that is how it should be.

This is the first of two articles about Israel.

Previous page

Previous page