ANATOMIST OF SNOBS

Paul Webb enjoys

the early journalism of Thackeray

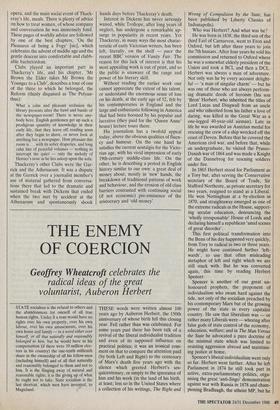

DOMINATING the Strangers' Room in the Reform Club is a painting of William Makepeace Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair and other novels, journalist, satirist, and travel writer, who died on Christmas Eve 125 years ago.

Guests who are taken to dine there are invariably struck by the great man's pugna- cious expression, which belies the promise of his middle name. Thackeray's broken nose (the result of a schoolboy brawl at Charterhouse) lends him an aggressive air, enhanced by his smart clothes and confi- dent posture, both of which proclaim that here is a gentleman as good as anyone in the room.

Thackeray's class and background ex- plain many of his tastes, accounting for his love of clubs, good wine, food and fel- lowship. The circumstances of his life, which forced an otherwise indolent man into a career as a prolific writer, explain the detached observation of society which produced both his engaging humour and an almost savage cynicism about the motives for human behaviour.

Born in Calcutta to a wealthy official of the East India Company who died when his son was only three, Thackeray was an only child who was nevertheless packed off to school in England at the age of five. He loathed the brutality and philistinism of the schools of that period, and subsequently insisted on his daughters being privately educated at home.

He had hoped to make a career as an artist, studying in Paris after cutting short his time at Cambridge and undertaking a tour of Germany. Thackeray's first contact with Dickens, whom he was later to rival as the most popular novelist of the day (Mrs Carlyle thought that 'he beats Dickens out of this world'), was when he unsuccessfully applied for the position of illustrator of the Pickwick Papers.

Although he continued to draw, and illustrated many of his articles and books, it was as a writer that he finally made his living. He was forced to do so when the collapse of his bank entailed the loss of his inheritance, much of which he had already squandered on the level of expenditure considered necessary for a young gentle- man. The young man made suddenly desti- tute was to be a recurrent theme in his novels.

As well as covering his own needs, he also had a wife and two daughters to provide for; a situation complicated by the mental illness that his wife developed after the birth of their later child, and which required her to be cared for professionally away from the family. Journalism was not a gentleman's profession, and though he would wine and dine with fellow contribu- tors to Punch at set-piece dinners, there was always a social distance between them.

Novels, however, were both profitable and respectable, which is why Thackeray turned towards them. After the enormous success of Vanity Fair, which demonstrated the vitality, characterisation and sharp social observation that make his journalism so enjoyable, he deliberately toned down his later works, setting them in innocuously antique periods, such as the reign of Queen Anne. As well as with his novels, he popularised the period with the building of a house at 2 Palace Gate, overlooking Kensington Palace. This, 'the reddest house in all the town', helped create the Queen Anne revival in architecture.

Given the restraint and lack of topicality of his later novels, it is to his journalism that one must turn to see Thackeray at his best. Commenting on the earlier writings that are currently unavailable to the gener- al public, Orwell wrote that if one wanted to choose something representative of Thackeray 'it would have to be The Book of Snobs or the burlesques, or a collection of his contributions to Punch'. This is what The Book of Snobs is, a collection of the satirical articles that were published in Punch as The Snobs of England, by one of Themselves. In it Thackeray looks not just at social climbers, but at all people with social affectations and pretentions, from Royalty down. Among the chapters are: 'The Snob playfully dealt with'; 'Dining- out Snobs'; 'Party-Giving Snobs'; 'On Clerical Snobs and Snobbishness'; and, largest of all, 'Club Snobs'.

As narrator, Thackeray swung on both sides of the issue. To illustrate that one can be snobbish on particular subjects with people with whom one otherwise gets on, he tells of how he had to 'drop' a friend whom he observed eating peas with a knife: 'After having seen him thus publicly comport himself, but one course was open to me — to cut his aquaintance.' A few pages later he concludes the chapter on the influence of the aristocracy with fatalism, 'how should it be otherwise in a country where Lordolotry is part of our creed, and where our children are brought up to respect the Peerage as the Englishman's second bible?'

A further example of his earlier work is the Sketches and Travels in London. The domestic nature of this book contrasts with the other, travel, books that recorded his experiences in Paris, Ireland, and the Middle East. The Sketches looks at Lon- don Society and describes trips to balls, the opera, and the main social event of Thack- eray's life, meals. There is plenty of advice on how to treat women, of whose company and conversation he was immensely fond. These pages of worldly advice are followed by one of the best chapters, 'On the Pleasures of being a Fogy' [sic], which celebrates the advent of middle age and the gentle descent into comfortable and clubb- able bachelordom.

Clubs played an important part in Thackeray's life, and his chapter, 'Mr Brown the Elder takes Mr Brown the Younger to a Club', describes a tour of one of the three to which he belonged, the Reform (thinly disguised as The Polyan- thus):

What a calm and pleasant seclusion the library presents after the bawl and bustle of the newspaper-room! There is never any- body here. English gentlemen get up such a prodigious quantity of knowledge in their early life, that they leave off reading soon after they begin to shave, or never look at anything but a newspaper. How pleasant this room is ... with its sober draperies, and long calm line of peaceful volumes — nothing to interrupt the quiet — only the melody of Homer's nose as he lies asleep upon the sofa.

Thackeray's other Clubs were the Gar- rick and the Athenaeum. It was a dispute at the Garrick over a journalist member's use of material gathered from conversa- tions there that led to the dramatic and sustained break with Dickens that ended when the two met by accident at the Athenaeum and spontaneously shook hands days before Thackeray's death.

Interest in Dickens has never seriously waned, while Trollope, after long years of neglect, has undergone a remarkable up- surge in popularity in recent years. Yet Thackeray, in many ways the most charac- teristic of early Victorian writers, has been left, literally, on the shelf — pace the recent BBC version of Vanity Fair. The reason for this lack of interest is that his most appealing work is out of print, and so the public is unaware of the range and power of his literary skill.

Without reading the earlier work one cannot appreciate the extent of his talent, or understand the enormous sense of loss on his death, at the early age of 52, felt by his contemporaries in England and the large and enthusiastic following in America that had been boosted by his popular and lucrative (they paid for the 'Queen Anne' house) lecture tours there.

His journalism has a twofold appeal today, above the obvious qualities of fluen- cy and humour. On the one hand he satisfies the current nostalgia for the Victo- rian age, with his vivid impression of early 19th-century middle-class life. On the other, he is describing a period in English history similar to our own: a great deal of money about, mostly in 'new' hands, the breakdown of traditional patterns of work and behaviour, and the erosion of old class barriers contrasted with continuing social (if not economic) pre-eminence of the aristocracy and 'old money'.

Previous page

Previous page