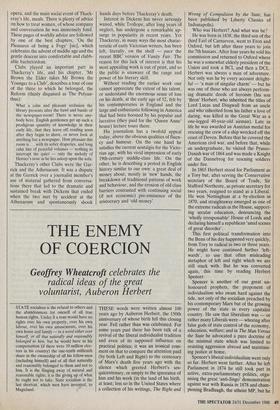

THE ENEMY OF COERCION

Geoffrey Wheatcroft celebrates the

radical ideas of the great voluntarist, Auberon Herbert

STATE socialism is the refusal to others and the abandonment for oneself of all true human rights. Under it a man would have no rights over his own property, over his own labour, over his own amusements, over his own home and family — in a word either over himself, or all that naturally and reasonably belonged to him, but he would have as his compensation (if there were 10 million elec- tors in his country) the one-tenth millionth share in the ownership of all his fellow-men (including himself) and of all that naturally and reasonably belonged to them and not to him. It is the flinging away of. natural and reasonable rights; it is the giving up of what he ought not to take. State socialism is the last shortcut, which men have invented, to Magicland. THESE words were written almost 100 years ago by Auberon Herbert, the 150th anniversary of whose birth fell this closing year. Fell rather than was celebrated. For some years past there has been talk of a revival of the liberal individualist tradition and even of its supposed influence on practical politics; it was an ironical com- ment on that to compare the attention paid (by both Left and Right) to the centenary of Marx's death five years ago with the silence which greeted Herbert's ses- quicentenary, or simply to the ignorance of him and his work (in the land of his birth, at least; less so in the United States where a collection of his writings, The Right and Wrong of Compulsion by the State, has been published by Liberty Classics of Indianapolis).

Who was Herbert? And what was he?

He was born in 1838, the third son of the third Earl of Carnarvon, went to Eton and Oxford, but left after three years to join the 7th hussars. After four years he sold his commission and returned to Oxford where he was a somewhat elderly president of the Union and took a BCL and then a DCL. Herbert was always a man of adventure. Not only was he by every account delight- ful — 'a man of singular charm' — but he was one of those who are always perform- ing dramatic deeds of heroism (his son 'Bron' Herbert, who inherited the titles of Lord Lucas and Dingwall from an uncle and who inherited from his father a love of daring, was killed in the Great War as a one-legged 40-year-old airman). Late in life he was awarded an Austrian medal for rescuing the crew of a ship wrecked off the coast of Devon. Before that he covered the American civil war, and before that, while an undergraduate, he visited the Prusso- Danish war of 1864 and was made a Knight of the Dannebrog for rescuing soldiers under fire.

In 1865 Herbert stood for Parliament as a Tory but, after serving the Conservative secretary of the Board of Trade, Sir Stafford Northcote, as private secretary for two years, resigned to stand as a Liberal. He won Nottingham at a by-election in 1870, and straightaway emerged as one of the extreme radicals in the House, support- ing secular education, denouncing the 'wholly irresponsible' House of Lords and declaring himself a republican 'amid scenes of great disorder'.

This first political transformation into the Benn of his day happened very quickly, from Tory to radical in two or three years. He might have continued further 'left- wards', to use that often misleading metaphor of left and right which we are still stuck with. But he was converted again, this time by reading Herbert Spencer.

Spencer is another of our great un- honoured prophets, the proponent of individualism who swam hard against the tide, not only of the socialism preached by his contemporary Marx but of the growing power of the state in every capitalist country. He saw that liberalism was — or rather many Liberals were — whoring after false gods of state control of the economy, education, welfare; and in The Man Versus the State he advocated a pure doctrine of the minimal state which was limited to resisting aggression abroad and maintain- ing justice at home.

Spencer's liberal individualism went only so far. Herbert went further. After he left Parliament in 1874 he still took part in active, extra-parliamentary politics, orga- nising the great 'anti-Jingo' demonstration against war with Russia in 1878 and cham- pioning Bradlaugh, the atheist MP, but he really discovered himself and his principles on paper. In 1884 he published a book with the engaging title A Politician in Trouble with his Soul which dissects the present system and the corrupting effects of party politics. In 1890 he began his own little weekly, Free Life. It later went monthly (an idea whose time had not come?) as the 'Organ of Voluntary Taxation and the Voluntary State'; more pamphlets and articles followed; another summary of his thoughts was published posthumously as The Voluntaryist Creed'.

All his life Herbert loved the country- side. He farmed near Lymington, then, after his wife's death, near Burley in the New Forest. He was addicted to outdoor exercise, a horseman, yachtsman, moun- taineer and early bicyclist; but although as a young man he was an enthusiastic field sportsman, he foresook killing animals, and then eating flesh, on a principled objection to taking life. He was a conserva- tionist, who worked hard to preserve the character of the New Forest, he collected prehistoric remains, he interested himelf in psychic research (alas, but it was the craze of the time), he annually entertained 'all corners, without distinction of class, to the ultimate number of several thousands, the gypsies clearing off all the remains', and he died in 1906 loved by all who knew him.

This is the portrait of a great and attractive Victorian eccentric. Herbert was more than that. He was writing at a critical moment, as the Victorian age of improve- ment had already much enlarged the power of the state and as socialism, emerging from its catacombs, was being combatted sometimes by repression, sometimes by stealing its clothes. Bismarck tried both: Herbert was scornful of the attempt to destroy the German Social Democrats by 'the foolish and useless weapon of repres- sive laws'. He made the best of all argu- ments for free speech, speaking as it were as an anti-socialist German liberal: 'You have driven the socialists into silence . . . yet for all that the movement goes on more ,actively than ever underground and hidden from sight. And we who are opposed to socialism are also silenced. . . How can we answer or reason with those who speak and write no word in public?' And at the same time the first steps to create an all- powerful, all-nourishing welfare state were taken also by Bismarck, the most inven- tive reactionary of modern times.

As Herbert saw, the deepest moral objection to socialism — even to mild reformist welfarism — is that it must be coercive: 'Every thorough-going socialist, who is willing to deal frankly with the matter, will admit that socialism rests on the cornerstone of force.' The justification for this use of force was the popular will, the decision of the majority. Socialists

'deny the rights of the individual to regulate and direct himself. But you suddenly ack- nowledge and exaggerate these rights as soon as you have thrown the individual into that mass which you call the majority. Then you suddenly discover that men have not only rights to own themselves, but also to own their fellow-men. But where have these rights come from? By what hocus-pocus, by what magic have they been brought into existence? A man who makes one of the exactly equal halves of a crowd has no rights, either as regards himself or as regards others; if he makes one in that part of the crowd which is larger by the tenth or the hundredth or the thousandth part, then he is clothed with absolute powers over himself and others. Did Central Africa ever produce a more absurd superstition?'

Not only is coercive welfare morally unjus- tifiable, it is inefficacious as it saps individual enterprise and reliance: No amount of Factory Acts will make us better parents', he says, 'no amount of state education will make a really intelligent nation'; and any- one who sneers at that might like to try a month's daily reading of the Sun.

At the time Herbert wrote, the Liberals had begun their long disintegration, aris- tocratic Whigs joining their Tory cousins over the Irish question (on which Herber was succinct: 'Ireland to choose its own government. The N.E. part to stay with England if it wishes to do so,' this the year before the first Home Rule Bill), bourgeois radicals already drifting towards social democracy and statism. Even Spencer dis- appointed, with his 'constant undertone of cynicism'. Herbert saw beyond this. One of his insights was to anticipate and refute the great lie of the 20th century, that there is only an either-or choice. This can take particularly insidious forms; 50 years ago, the lie said that there was no choice except fascism on the one hand, communism on the other. More generally it says that the only alternatives are obscurantist reaction, and some variety of state socialism. There is another way.

He was indeed a radical — going to the roots. Herbert developed a programme. All monopolies and restraints which pre- vent the people from gaining the full bene- fits of free trade will be abolished, inclu- ding the state post office and state regula- tion of the professions of law and medicine. Then, abolition of those services done by the state, such as state education, estab- lished churches, poor laws, state regulation of factories, mines and ships. This would promote greater independence of charac- ter, greater intelligence, enterprise and fitness for voluntary association. These measures would be followed by the aboli- tion of laws attempting to enforce opinions (such as the 'oaths which led to the nationally disgraceful expulsion of Mr Bradlaugh') or enforcing a special observ- ance of the Sunday or suppressing brothels.

All of these are contingent on Herbert's central policy:

Abolition of all custom and excise duties and assessed taxes, and establishment of complete free trade in all things. All govern- ment revenues (whether central or local) to be derived from voluntary, not compulsory payments.

Apart from the argument of convenience, which unfortunately governs us in so many matters, it will be difficult, I think, to find any real justification for the compulsory levying of taxes. The citizens of a country who are called upon to pay taxes have done nothing to forfeit their inalienable right over their own possessions (it being impossible to separate a man's right over himself and his right over his possessions), and there is no true power lodged in any body of men, whether known under the title of govern- ments or gentlemen of the highway, to take the property of men against their consent.

This may strike some as a reductio ad absurdum of individualism; is it more absurd than that reduction of statism under which we in effect live, which holds that all property belongs to the state and is loaned back to individuals only by favour?

Herbert not only went beyond Spence- rian individualism, he saw to the heart of the other — not great lie, but great misunderstanding of the age: that the choice is between individualism and collec- tivism. Put like that (as liberal individual- ists too often do) individualism is open to the objection that almost all human activities are collective: 'Mr Hobson justifies socialism — or the compulsory organisation of all human beings — by the fact of our social inter- dependence.' Herbert was addressing one of his intellectually worthiest opponents, J. A. Hobson. But the vital choice is not between the individual and the collective but between the voluntary and the coer- cive. The great political question of our time is not the class struggle but the power of the state, and to that socialism offers no more of an answer than does reaction. It does not even address Herbert's contention 'that there is no moral foundation for the exercise of power by some men over others, whether they are a majority or not', or answer his 'great question', 'By what right do men exercise power over each other?'

There was a further objection, which Hobson made in the title of his article on Herbert: 'Rich Man's Anarchism'. Herbert dealt with this charge — that his political ideal is a bourgeois or indeed aristocratic fantasy. But in any case, his argument is even stronger now. During the century since Herbert wrote it has sometimes looked as if his ideas were hopelessly impractical. The Age of Reason gave way to the Age of Power and not only indivi- dualism but liberalism itself was squeezed Out by militaristic nationalism and Marxism. Today, Herbert seems wiser than ever. 'The poor' in the old sense, the helpless propertyless mass of the people, are disappearing in advanced countries and with them any ostensible excuse for the great machine of statist coercion. As we approach the end of this century we see that socialism is an idea whose time has come, and gone. Auberon Herbert was the man of the future.

Previous page

Previous page