Kenneth Hurren on suffering with the faithful

On the night last week when I saw John Kerr's play, Mistress of Novices, at the Piccadilly Theatre, there were more priests on hand than you'd expect to find in the paddock at the Curragh races, and my suspicion is that the rest of the audience consisted mainly of their various flocks. I guess as much, anyway, from the respectful attention they accorded the play, which would very probably strike a more regular West End theatregoer as some dismaying species of purgatory.

From which you will guess in turn, and rightly, that the mistress of the title is of a different kind from that usually featured in the palaces of entertainment around the hub of our nation's capital, and that the novices are convent postulants, and furthermore that there are none of those unseemly, even lurid, goings-on which our dissolute age has come to expect of any dramatic exploration of the enclosed life. This is all very straight-faced, not to say po-faced, stuff, and has to do with a young woman named Marie-Bernarde Soubirous, even in her own time .popularly known as Bernadette of Lourdes.

Since I'm not too well up in hagiography, I cannot say positively that Kerr has stuck closely to the facts of the matter, but I am bent to that view, if only on the grounds that if he were going to invent a story he would almost certainly have invented a better one. There is also the manner in which he goes doggedly out ot his way to seem soberly and documentarily accurate, as, for example, in having two readers — one at each side of the stage, and both dressed, as nuns — standing at lecterns and keeping us supplied with the vital background and chronological material: " Nevers, 1866 — it is the twer.ty-ninth of June, the Feast of St Peter and St Paul, when..." and we're away.

It is eight years after the Lourdes affair, and Bernadette is already of sufficient celebrity to have half the nunneries in France after her when it is known that she has been moved to take the veil. St Gildard's at Nevers ,is not one of them, tht Reverend Mother there taking the view , that seeing Visions, admirable in its way, is of no practical help in the work of the Order; nor is she prepared to risk the discipline and pecking order going to pot because of the presence of a superstar in the junior ranks. Nevertheless the church, in its inscrutable wisdom, has decreed that this is the place for her (lest, elsewhere, she be betrayed disastrously into the sin of pride).

Bernadette proves to be an engaging little dunce and quickly wins nearly all hearts, but it is there that her luck runs out and she comes up against the eponymous senior nun, Marie-Therese, the villainess of Kerr's piece. What, we must ask ourselves, is the motive for this strange woman's insistence on giving poor Bernadette such a hard time? (The hapless youngster is rarely off her knees — what with praying, scrubbing and just plain kissing the floor in penance — and eventually develops a tubercular, and fatal, tumour of the leg.) The initial suggestion is that simple envy is behind this campaign of humiliation and persecution: MarieTherese clearly feels that her own lifelong and professional devotion to the Virgin should have earned her priority over the Lourdes peasant if there were any visitations going. In the rather specialised context, I daresay this would seem a plausible enough explanation, but it is not quite the one we get. Marie-Therese, it transpires, is merely the instrument of God, the confirmation of the bad news communicated to Bernadette in her Vision that the way of the saint is tough.

The truth doesn't dawn on Marie Therese herself until she is an embittered eighty-year-old and her victim has been dead for thirty years. Her reaction seemed to me understandably glum, but I think it is intended that the faithful should find it somehow warm and comforting and take it to their hearts, and I hope their spiritual mentors won't have too many disconcerting questions to cope with when they a11 get back to their parishes; for if it is not a comfort to the converted then it is nothing much of anything. It is unlikely to soothe the difficulties of those who may be troubled by the whimsical behaviour of an omnipotent and reputedly merciful God who is given the credit for healing the afflicted but absolved of responsibility for the afflictions. Teasing questions of this kind do not raise their knotty heads; nor is there any serious doubt cast upon the authenticity of Bernadette's encounter with the Virgin Mary (" I am the Immaculate Conception," she is said to have said, just like that); and I must also dash your hopes that the subject might encourage some discussion of the faith healing industry and the ethics of the church's promotion of it.

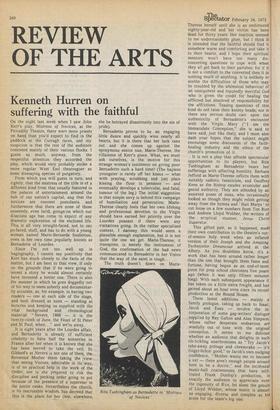

It is not a play that affords spectacular opportunities to its players, but Rita Tushingham as Bernadette bears her sufferings with affecting humility, Barbara Jefford as Marie-Therese inflicts them with suitably sadistic fanaticism, and Geoffrey Keen as the Bishop exudes avuncular and genial authority. They are attended by an assorted posse of nuns, who occasionally looked as though they might relish getting away from the hymns and 'Hail Marys' to cut loose on a few numbers from Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber, the writers of the sceptical stunner, Jesus Christ Superstar.

This gifted pair, as it happened, made their own contribution to the theatre's outof-season holy week when an inflated version of their Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat arrived at the Albery. As you doubtless know, it's a work that has been around rather longer than the one that brought them fame and fortune, having begun as an end-of-term piece for prep school choristers five years ago (when it was only fifteen minutes long). With each subsequent appearance it has taken on a little extra freight, and has gained about an hour even since its recent production at the Round House.

These latest additions — mainly a family prologue, taking us back to Isaac, Jacob and Esau — involve the incorporation of some gag-writers' dialogue supplied by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, whose rather desperate endeavous are woefully out of tune with the original conception. It seems to me dubious whether an audience that delights in such rib-tickling anachronisms as "Try Jacob's take-away pottage and cheesecake — it's finger-lickin' good," or Jacob's own nudging confidence, "Mother wants me to become a vet — there aren't enough people around here to be a doctor," and the incidental music-hall coarsenesses that have infiltrated Frank Dunlop's production, is exactly the audience to appreciate even the ingenuity of Rice, let alone the genuis of Lloyd Webber, whose music is almost as engaging, diverse and complex as his score for the team's big one.

Previous page

Previous page