ARTS

Exhibitions

Wright of Derby (Tate Gallery, till 22 April)

More wrong than Wright

Giles Auty

ronically, the Tate's current exhibition of the 18th-century artist Wright of Derby tells us even more about the parlous state of art in Britain today than does the destination of that gallery's annual Turner Prize awarded for making contemporary artefacts. Whether the latter bun-fight has become more discredited now that the firm of American junk-bond dealers sponsoring it has collapsed I would not care to say. What this self-important staging of the works of Wright of Derby tells us on the other hand is that our critical standards are possibly still further up the creek than even I had supposed. After all, awarding the Turner Prize last year to Richard Long, a sponsored walker and manufacturer of circles in slate and mud, reflects only on art's current weak-kneed modishness, whereas promoting Wright of Derby as an internationally important artist of the 18th century — or of any other time — shows we are no longer able to separate truly good painting from the often mawkish and indifferent. That is really serious.

The Tate's Wright of Derby exhibition goes on tour later to the Grand Palais in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. One hundred and fifty oil Paintings, a score or more of supporting works plus a finely produced catalogue inform us that here is an exhumed reputa- tion all of us had better take seriously. Every detail, down to the ponderous weight of the catalogue, has been designed to drive the message home. Perhaps best of all, Wright of Derby's provincially laced cognomen sounds like that of someone quite likely to have been dismissed unfairly in the past as parochial. Surely this last will become a rallying ground for all who defend the chip buttie or Birmingham accent as worthy forms of regional express- ion.

Writing of Velazquez last week I sug- gested that that great master's art helped establish a language of qualitative compari- son which remains appropriate; I concur With Manet's view that Velazquez was just about the best Western painter we are ever likely to see. If, as I maintain, painting is a Product in which the activities of hand, head and heart are able to perform in concatenation, then Wright of Derby shows serious shortcomings in two if not all three of these areas. At his very best, as in 'An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump' or 'A Philosopher giving that Lec- ture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in Place of the Sun', Wright of Derby appears an admirable and very interesting artist. However, at his more common worst, Wright was wooden, mannered and grossly sentimental to a degree no artist of lasting significance has ever been. Art commentators of the past' Samuel and Richard Redgrave also admired The Air Pump' but remarked of the rest of Wright's works that 'when placed beside the works of Reynolds or Gainsborough, they remind us of the labours of a house-painter'. Although Reynolds himself painted some thoroughly indifferent works, the compari- son the Redgraves made with Gains- borough may strike many as continuingly apt.

Judy Egerton, principal organiser of the exhibition, prefers to see such things in a different, seemingly more modern and

liberal light: 'Artists are, or should be, different from each other. Wright is not elevated by putting down Reynolds nor are his gifts easily measured against Gains- borough's. . .' To those who bother to walk round this exhibition with their eyes open, this last comment may seem patently untrue. Indeed, those who would seek to learn anything at all about art should try to make comparisons not only between artists of the same century but between those of different eras too. This is how we come to recognise the existence of perennial vices and virtues in painting and learn to diffe- rentiate between the journeyman and the master. Wright of Derby aspired occa- sionally to the latter condition but was more often pedestrian or worse in his ideas no less than in his execution. Wright's portraiture, of which many examples are on view, was inclined to be stiff, conven- tional aqd unfocused, whereas his land- scapes and history paintings, by contrast, were more frequently overcooked than underdone. Further, Wright's command of tone and breadth were generally unreliable and his posing of models histrionic. Wright was a worthy artist with occasional flashes of genius yet ultimately neither he — nor his patrons presumably — could resist the picturesque and sentimental. In short, as even a discerning visitor from New Jersey may say of Wright when the show travels on to New York: `Gainsborough he wasn't.'

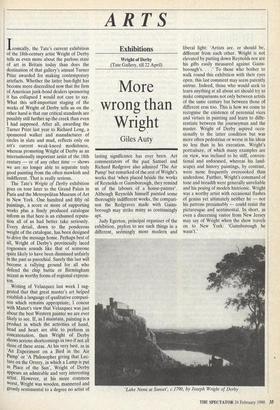

'Lake Nerni at Sunset', c.1790, by Joseph Wright of Derby

Previous page

Previous page