ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Frederic Leighton (Royal Academy, till 21 April) Leighton and his sculptural legacy (Matthiesen Gallery, till 22 March) Relentless Perfection (Leighton House, till 21 April) The Leighton Frescoes (Victoria and Albert, till 8 September)

The Admirable Crichton

John Spurling

0 ne of Frederic Leighton's obituaries a century ago suggested that his art was `perhaps too genuinely artistic for the Anglo-Saxon temperament'. He was brought up mostly abroad, trained in Flo- rence, Berlin, Frankfurt, Rome and Paris, and did not settle in London until he was almost 30 years old and had already declared his large international ambitions with a painting more than two metres high and five metres long. `Cimabue's Madonna' was painted in Rome when he was 25 and at first was intended for a Paris premiere. In the event, it appeared at the Royal Academy and was immediately snapped up by Queen Victoria as a present for Albert. Receiving this heady news in Rome, Leighton characteristically celebrated not by getting drunk but by buying paintings from his friends.

He was affectionately known as 'The Admirable Crichton' for his remarkable combination of social graces and linguistic as well as artistic abilities with a lofty sense of duty and iron self-control; but he also had his detractors. George du Maurier (by way of being a friend) said he was 'very blasé and finikin, and quite spoilt', some- body else called him a fop, his predecessor as president of the Royal Academy loathed him and Henry James satirised him in The Private Life as Lord Mellifont who was `first — extraordinarily first — essentially at the top of the list and the head of the table'.

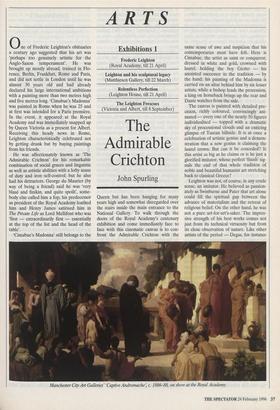

`Citnabue's Madonna' still belongs to the Queen but has been hanging for many years high and somewhat disregarded over the stairs inside the main entrance to the National Gallery. To walk through the doors of the Royal Academy's centenary exhibition and come immediately face to face with this cinematic canvas is to con- front the Admirable Crichton with the same sense of awe and suspicion that his contemporaries must have felt. Here is Cimabue, the artist as saint or conqueror, dressed in white and gold, crowned with laurel, holding the boy Giotto — his anointed successor in the tradition — by the hand; his painting of the Madonna is carried on an altar behind him by six lesser artists, while a bishop leads the procession, a king on horseback brings up the rear and Dante watches from the side.

The canvas is painted with detailed pre- cision, richly coloured, convincingly ani- mated — every one of the nearly 50 figures individualised — topped with a dramatic sky of processional clouds and an enticing glimpse of Tuscan hillside. It is at once a celebration of artistic genius and a demon- stration that a new genius is claiming the laurel crown. But can it be conceded? Is this artist as big as he claims or is he just a glorified imitator, whose perfect 'finish' sig- nals the end of that whole tradition of noble and beautiful humanist art stretching back to classical Greece?

Leighton was not, of course, in any crude sense, an imitator. He believed as passion- ately as Swinburne and Pater that art alone could fill the spiritual gap between the advance of materialism and the retreat of religious belief. On the other hand, he was not a pure art-for-art's-saker. The impres- sive strength of his best works comes not just from its technical virtuosity but from its close observation of nature. Like other artists of the period — Degas, for instance Manchester City Art Galleries' Captive Andromache, c. 1886-88, on show at the Royal Academy — he was trying to re-attach the ideal forms of past masters to material realities. His figures are living people, unashamedly Victorian as well as Renaissance, Biblical or Classical, and he mainly succeeded in avoiding the unearthly soppiness that afflicts the idealised figures in the work of most of his British contemporaries. He was not so much a revivalist as a renewer, in the forefront — at any rate in his middle years — of an impetus to raise art and culture in general above its previously humble status.

He did not become president of the Royal Academy because he thought it an end in itself but because he saw it as part of his programme, and he transformed the place into an institution almost as august as the Church of England. The extraordinary thing is that having become, as it were, the Archbishop of Art — with all that entailed by way of committee-work, lobbying, in- fighting and socialising — he still had the energy and the will to continue taking risks as an artist. In at least half a dozen of the late paintings from the presidential period of his life, he redeemed the promise of `Cimabue's Madonna' with audacious maturity.

This splendid exhibition, grandly but plainly laid out, supported with a particu- larly thorough and well-written catalogue (by a team of five scholars, led by Richard Ormond), has no reservations about con- ceding Leighton his crown of laurel, at least in the context of his time. Time, of course, is the rub: Leighton's time, in that he was coeval with artists such as Monet, Cezanne, Seurat and Gauguin who were disrupting if not utterly destroying the Classical/Renaissance tradition; and our time, in that we come to look at him again at the end of another century in which art — not to speak of life — has been through every sort of violent contortion.

That Leighton cannot be simply dis- missed as a reactionary is proved by his sculpture. He had begun to make small preliminary models of some of the figures for his paintings and this led him, with the help of his sculptor friend Thomas Brock, to attempt a full-scale, finished work. The result — 'An Athlete Wrestling with a Python' — became one of the most influen- tial pieces of its day and, with its only two successors, 'The Sluggard' and the smaller- scale 'Needless Alarms', helped to initiate the so-called 'New Sculpture'.

Leighton's two large finished sculptures as well as some of his sculptural models for paintings are included in the RA show, but his effect on other young sculptors such as Alfred (Tros') Gilbert, Hamo Thornycroft and Robert Browning's son Pen — many of whom Leighton personally helped and encouraged — can be seen in a special exhibition organised by Joanna Barnes at the Matthiesen Gallery.

The paintings, however, had no succes- sors. Even before he died, at 65, Leighton was beginning to seem outmoded, while we, over this populist century, have learnt to associate sketchiness with inspiration, the rough and rugged with emotional hon- esty and anything too posed, poised or per- fected with the over-intellectual and academic. 'Leighton,' says The Oxford Companion to Art witheringly, 'was a man whose culture surpassed his achieve- ment.'

That view may be tenable when you look at reproductions of his work, but not in front of the orange brilliance of 'Flaming June', the austere sensibility of `Nausicaa', the glowing twilight of `Cymon and Iphege- nia', the shimmering pink-orange-yellow lights of 'The Garden of the Hesperides'. None of these has much to do with culture in the literary sense. The titles are almost as unimportant as the titles of modern abstracts, mere handrails into a world of passionate and minutely explored feelings about nature, the human body (mainly female and based on Leighton's favourite model, Dorothy Dene) and light, together with the colour and form that transform them into art.

`Captive Andromache' (nearly as large as `Cimabue's Madonna') is a graver, more intellectual work, though what it depicts is superficially nothing but a queue. Women and girls in variously coloured, diaphanous classical drapes, waiting to fill their jugs at a cistern, spread across from shadow into full sunlight, while Andromache, heavily draped in black, her head bowed, stands silhouetted at the centre. Leighton is not at his best with Biblical or Classical scenes of direct action and external emotion, which look merely Victorian theatrical, but 'Cap- tive Andromache' speaks for any time, from the Trojan War until now. One does not need to know Andromache's story to see and feel the internal darkness of this person's loss and grief in the middle of the mundane, daylight insouciance of the rest.

No other art but the slowly unfolding one of painting could make this subject work with such simplicity and depth and perhaps no other painter — unless Poussin — would have attempted anything like it, let alone achieved it on such a scale and with such a degree of finished deliberation. Leighton was a master, though we may have to break through thick layers of our own prejudice and Anglo-Saxon tempera- ment to recognise it.

Leighton House (12 Holland Park Road, London W14) is celebrating its former owner's centenary with Relentless Perfec- tion: At Home with Lord Leighton, a drama- tised tour of the interior as Leighton would have inhabited it. The two huge frescoes of `War' and 'Peace' which he made for the V & A's South Court are still hopelessly cramped by the rebuilding that took place after the second world war and difficult to see, but a display of their preparatory drawings and oil sketches with a full-size cartoon of 'Peace' give some idea of what the admirable, indefatigable Leighton put into everything he did.

Previous page

Previous page