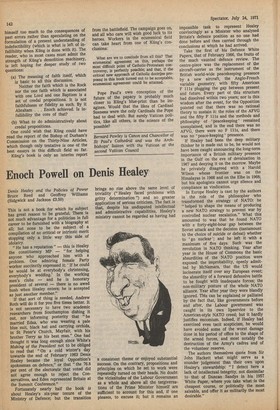

Enoch Powell on Denis Healey

Denis Healey and the Policies of Power Bruce Reed and Geoffrey Williams (Sidgwick and Jackson £3.50) This is not a book for which its subject has great reason to be grateful. There is not much advantage for a politician in full career to be furnished with a biography at all; but none to be the subject of a compilation of no critical or intrinsic merit stopping only a little way this side of idolatry.

"He has a reputation" — this is Healey the constituency MP — "for helping anyone who approached him with a problem. One admiring female Party worker succinctly expressed it: 'If he could he would be at everybody's christening, everybody's wedding.' In the working men's clubs — and he is honorary president of several — there is no awed hush when Healey enters; he is accepted as just another member."

If that sort of thing is needed, Andrew Roth will do it for you five times better. It is not necessary to have two academic researchers from Southampton dishing it out, nor informing posterity that "he married Edna, who was wearing a pale blue suit, black hat and carrying orchids, in St Peter's Church, Mayfair, with his brother Terry as his best man." One had thought it was long enough since White's Making of the President not to be obliged to read that "On a cold winter's day towards the end of February 1963 Denis Healey became the loyal Opposition's spokesman on defence," or that "the 76.8 per cent of the electorate that voted did not agree enough to reject the Conservatives, and Eden represented Britain at the Summit Conference."

Fortunately nearly half the book is about Healey's six-year tenure of the Ministry of Defence; but the transition brings no rise above the same level of triviality (" Healey faced problems with gritty determination ") and no greater application of serious criticism. The fact is that, despite his undisputed intellectual and administrative capabilities, Healey's ministry cannot be regarded as having had a consistent theme or enjoyed substantial success. On the contrary, propositions and principles on which he set to work were repeatedly turned on their heads. No doubt the vicissitudes of the Labour Government as a whole and above all the tergiversations of the Prime Minister himself are sufficient to account for this and, if one pleases, to excuse it; but it remains an

Previous page

Previous page