WE'RE CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE

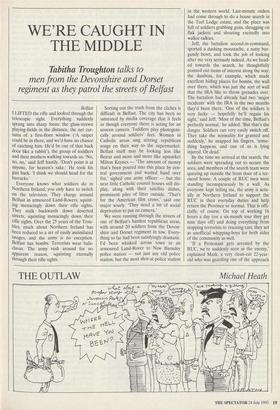

Tabitha Troughton talks to

men from the Devonshire and Dorset regiment as they patrol the streets of Belfast

Belfast I LIFTED the rifle and looked through the telescopic sight. Everything suddenly sprang into sharp focus: the glass-strewn playing-fields in the distance, the net cur- tains of a first-floor window CA sniper could be in there, and we'd have no chance of catching him. He'd be out of that back door like a rabbit'), the group of toddlers and their mothers walking towards us. 'No, no, no,' said Jeff hastily. 'Don't point it at anyone, for heaven's sake.' He took his gun back. 'I think we should head for the barracks.'

Everyone knows what soldiers do in Northern Ireland; you only have to switch on the television. They charge around Belfast in armoured Land-Rovers, squint- ing menacingly down their rifle sights. They stalk backwards down deserted streets, squinting menacingly down their rifle sights. Over the 25 years of the Trou- bles, much about Northern Ireland has been reduced to a set of easily assimilated images, and the army is no exception. Belfast has bombs. Terrorists wear bala- clavas. The army rush around for no apparent reason, squinting eternally through their rifle sights. Sorting out the truth from the clichés is difficult in Belfast. The city has been so saturated by media coverage that it feels as though everyone there is acting for an unseen camera. Toddlers play photogeni- cally around soldiers' feet. Women in Catholic areas sing stirring republican songs on their way to the supermarket. Belfast itself may be looking less like Beirut and more and more like upmarket Milton Keynes — 'The amount of money that's been poured into this place by cen- tral government and wasted hand over fist,' sighed one army officer — but the neat little Catholic council houses still dis- play, along with their satellite dishes, prominent piles of litter outside. 'That's for the American film crews,' said one major sourly. 'They need a bit of social deprivation to put on camera.' We were running through the streets of one of Belfast's hardest republican areas, with around 20 soldiers from the Devon- shire and Dorset regiment in tow. Every- thing so far had been satisfyingly dramatic. I'd been whisked across town in an armoured Land-Rover to New Barnsley police station — not just any old police station, but the most shot-at police station in the western world. Last-minute orders had come through to do a house search in the Turf Lodge estate, and the place was full of soldiers grabbing guns, shrugging on flak jackets and shouting excitedly into walkie-talkies.

Jeff, the battalion second-in-command, sported a dashing moustache, a natty bur- gundy beret, and took the job of looking after me very seriously indeed. As we head- ed towards the search, he thoughtfully pointed out items of interest along the way: the dustbins, for example, which made excellent hiding places for bombs, the wall over there, which was just the sort of wall that the IRA like to throw grenades over. The battalion had already had two 'major incidents' with the IRA in the two months they'd been there. 'One of the soldiers is very lucky — hopefully he'll regain his sight,' said Jeff. 'Most of the time, Belfast's perfectly normal,' he added. 'But that's the danger. Soldiers can very easily switch off. They take the normality for granted and suddenly,' he snapped his fingers, 'some- thing happens, and one of us is lying injured. Or dead.'

By the time we arrived at the search, the soldiers were spreading out to secure the area, and members of the search team were queuing up outside the front door of a ter- raced house. A couple of RUC men were standing inconspicuously by a wall. As everyone kept telling me, the army is actu- ally in Northern Ireland to support the RUC in their everyday duties and help return the Province to normal. That is offi- cially, of course. On top of working 16 hours a day (on a six-month tour they get nine days off) and doing everything from stopping terrorists to rescuing cats, they act as unofficial whipping-boys for both sides of the community as well.

`If a Protestant gets arrested by the RUC, we're suddenly seen as the enemy,' explained Mark, a very clean-cut 22-year- old who was guarding one of the approach roads. The search had had a slight hiatus; there were no grown-ups in the house and the child inside insisted on talking to the soldiers through a bathroom window. 'The same thing happens with the Catholics. Then, of course, they're each other's ene- mies, and we're just caught in the middle.' He paused. 'Of course, we're really here to support the RUC and return the Province to normal,' he added belatedly.

Not that the locals seemed to appreciate it. `I'm sorry, are we in your way?' asked Jeff to the woman who found us some time later crouching in her driveway. The search was still going in the next street; they'd finally found a neighbour to open the back door. `Yes, you are,' she snapped. `You're always in the way. You shouldn't be here in the first place.' We were keep- ing low in case of snipers; but finding armed men crouching behind your car must eventually ruin even the most level of tempers.

Jeff agreed. 'Remember, we were actual- ly here to support the Catholicg in the first place. I'd say there's still a lot of sympathy among the lads for the civil rights cause,' he added. 'Lies and propaganda,' jeered a passing group of boys, who had seen my tape-recorder. Getting the community on their side is, say soldiers, equally as impor- tant as combating terrorism. The army now have a policy of community relations to minimise tensions; gazing menacingly through rifle sights is, apparently, on its way out. Being nice to people is in. 'And you have to understand their feelings for it to work,' said Jeff earnestly. `Being polite, smiling, it all helps. I think people's atti- tudes have changed, although it's obvious- ly difficult.'

Further down the road, Bill, one of sev- eral soldiers who looked about 12, was being besieged by a gang of Belfast urchins, average age about eight. 'Hello, lads,' he said valiantly. 'Fuck off,' they shouted. 'Now that's not nice language, is it?' said Bill gallantly. One started dancing around behind him, pulling at the commu- nications equipment on his back, while Bill tried ineffectually to stop him. Eventually, goaded beyond endurance, he gave up and went to stand with his back against a wall. I didn't need telescopic sights to see he looked depressed.

`You talk about compassion fatigue,' said a company commander at the bar- racks. 'The soldiers are now arriving at the point of abuse fatigue. There's only so much you can take. So what do you do? You get a punch-bag up in the gym and they can go and beat the living shit out of that, which helps a bit. You've got to have some way of dealing with the tension.' And it's not just the gangs of boys, although soldiers tend to wince when they're mentioned. Opinion was divided between which was worse: the stone-throw- ing (another regular feature of everyday life) or the catapults. Jeff went for the cata- pults. `They use steel ball-bearings, you know.' For one of his men, who must have been at least six feet tall, and who was looking for snipers at the time, it was the stone-throwers. `I think they're the most frightening, especially at night,' he volun- teered. `At least during the day you can dodge them. At night, you don't stand chance.'

Ask about the positive side of being in Northern Ireland, and soldiers will say it's the occasional excitement, the team sup- port, the fact that they save a lot of their salary because they're not allowed out of barracks to spend it, and that they're doing a real job. Some, who tend to be single, even ask to come back. 'By and large,' said Jeff firmly, as we were waiting for transport to take us back to the barracks, `we take comfort in the fact that we're preventing death or injury to a population which is largely innocent.' A stone bounced off his shoulder. The men around him ground their teeth. The battalion of the Devon- shire and Dorset regiment still have four months left to go.

Previous page

Previous page