ARTS

Exhibitions

The Impressionist and the City: Pissarro's Series Paintings (Royal Academy, till 10 October)

Pedestrian points of view

Giles Auty

Although they are plodding at times, one should be grateful to Camille Pissar- ro's paintings of Paris, Rouen, Le Havre and Dieppe for the pictorial sensation they provide of how blissful urban life could be for those on foot before the advent of the car, let alone of the modern, murderous motorcycle messenger.

The paintings in this exhibition date from the last years of the artist's life when he was already approaching 70 and trou- bled by an eye condition which made paint- ing out of doors a trial. In his earlier years Pissarro suffered consistent hardship and neglect although he was at the height of his powers. In 1883 he told Gauguin, 'I have worked for 30 years and here I am, on the rocks at 53'. In fact, from then until his death in 1904, Pissarro's fortunes improved somewhat, but it was not until the last years of his life, those covered by this exhibition, that Pissarro really found a ready market. His prolific output, at this juncture, for a man of his age was surely influenced by this last factor, although art historians disdain to make such obvious connections.

Until 1890 Pissarro concentrated on rural subject matter, often enduring the rigours of the seasons in pursuit of their transient effects of light, colour and atmosphere. Latterly and very understandably he preferred to paint from the vantage point of upstairs windows, a habit many painters have followed before and since for its comfort and conve- nience and for the interesting angles and compositions on offer. It is in this last area that I find Pissar- ro disappointing and repetitive. Compared with others who painted Paris, such as Gustave Caillebotte (1848-94), Pissarro composed his pictures conventionally and very conservatively. Only one painting of the considerable number on view at the Royal Academy contains no sky, sky generally and rather tediously accounting for about half the com- position. To look down more direct- ly from above seems never to have occurred to the artist in spite of the fascinating pictorial geometry such an acute viewpoint can bring into play. I find Pissarro's compositions in Paris, at least, pedestrian in one sense too many.

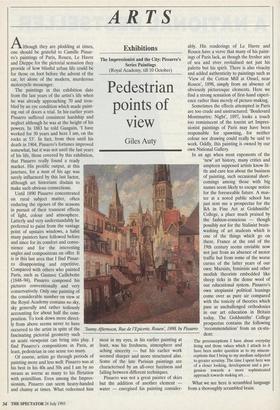

Of course, artists go through periods of painting more and less well: Pissarro was at his best in his 40s and 50s and I am by no means as averse as many to his flirtation with pointillism. Even among the Impres- sionists, Pissarro can seem heavy-handed and clumsy at times. What redeemed him `Sunny Afternoon, Rue de l'Epicerie, Rouen; 1898, by Pissarro most in my eyes, in his earlier painting at least, was his freshness, atmosphere and aching sincerity — but his earlier work seemed sharper and more structured also. Some of the late Parisian paintings are characterised by an all-over fuzziness and falling between different techniques.

Pissarro was not a great painter of skies but the addition of another element water — energised his painting consider- ably. His renderings of Le Havre and Rouen have a verve that many of his paint- ings of Paris lack, as though the fresher airs of sea and river revitalised not just his palette but his spirit. There is also vivacity and added authenticity to paintings such as `View of the Cotton Mill at Oissel, near Rouen', 1898, simply from an absence of obviously picturesque elements. Here we find a strong sensation of first-hand experi- ence rather than merely of picture-making.

Sometimes the effects attempted in Paris are too crude and unstructured: 'Boulevard Montmartre: Night', 1897, looks a touch too reminiscent of the tourist art Impres- sionist paintings of Paris may have been responsible for spawning, for neither colour nor drawing could really be said to work. Oddly, this painting is owned by our own National Gallery.

In an age when most exponents of the `new' art history, many critics and umpteen supposed artists know lit- tle and care less about the business of painting, such occasional short- comings among those with big names seem likely to escape notice for the foreseeable future. A mas- ter at a noted public school has just sent me a prospectus for the BA in Fine Art at Goldsmiths' College, a place much praised by the fashion-conscious — though possibly not for the Stalinist brain- washing of art students which is one of the things which go on there. France at the end of the 19th century seems enviable now not just from an absence of motor traffic but from some of the worse curses of the latter years of our own: Marxists, feminists and other modish theorists embedded like sheep ticks in the dense wool of our educational system. Pissarro's own utopianist political leanings come over as pure air compared with the toxicity of theories which pass as unchallenged orthodoxies in our art education in Britain today. The Goldsmiths' College prospectus contains the following `recommendation' from an ex-stu- dent: The preconceptions I have about everyday living and those values which I attach to it have been under question as to my miscon- ceptions that I bring to my medium subjected to greater scrutiny. The time I spent here was of a closer looking, development and a pro- gession towards a more sophisticated approach towards making art....

What we see here is scrambled language from a thoroughly scrambled brain.

Previous page

Previous page