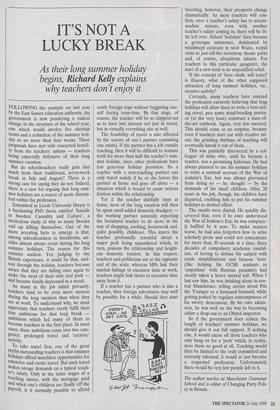

IT'S NOT A LUCKY BREAK

As their long summer holiday why teachers don't enjoy it

FOLLOWING the example set last year by the East Sussex education authority, the government is now pondering a radical change in the structure of the school year, One which would involve five shortish terms and a reduction of the summer holi- day to no more than four weeks. These proposals have met with concerted hostili- ty from the teachers' unions — teachers being especially defensive of their long summer vacation.

But do schoolteachers really gain that much from their traditional, seven-week break in July and August? There is a strong case for saying they do not. Indeed, there is a case for arguing that long sum- mer holidays are a source of acute discom- fort within the profession.

Entombed in Leeds University library is a fascinating PhD thesis entitled 'Suicide in Sweden: Causality and Culture', a meticulous study of why so many Swedes end up killing themselves. One of the more arresting facts to emerge is that, among schoolteachers in Stockholm, sui- cides almost always occur during the long summer holidays. The reason for this remains unclear. Yet, judging by the British experience, it could be that, mid- way through the holiday, teachers become aware that they are failing once again to make the most of their only real perk and become fatally depressed as a result. As many in the job admit privately, teachers tend to be even more morose during the long vacation than when they are at work. To understand why, we must appreciate that teachers rarely fulfil their true ambitions for that long break ambitions which led many of them to become teachers in the first place. In most Cases, these ambitions come into two cate- gories: prolonged travel and 'creative' activity. To take travel first, one of the great myths surrounding teachers is that summer holidays afford matchless opportunities for extensive and exotic travel. But such travel Makes savage demands on a typical teach- er's salary. Only in the latter stages of a teaching career, with the mortgage paid and when one's children are finally off the payroll, is it normally possible to afford costly foreign trips without beggaring one- self during term-time. By that stage, of course, the teacher will be so clapped-out as to have lost interest not just in travel, but in virtually everything else as well.

The feasibility of travel is also affected by the nature of one's partner (assuming one exists). If the partner has a job outside teaching, then it will be difficult to venture forth for more than half the teacher's sum- mer holiday, since other professions have less generous holiday provision. So a teacher with a non-teaching partner can only travel widely if he or she leaves the partner at home and goes off alone — a situation which is bound to cause serious friction within the relationship.

Yet if the teacher dutifully stays at home, most of the long vacation will then be spent amid added domestic drudgery the working partner naturally expecting the becalmed teacher to do more in the way of shopping, cooking, housework and, quite possibly, childcare. This leaves the teacher profoundly resentful about a major perk being squandered which, in turn, poisons the relationship and height- ens domestic tension. In this respect, teachers and politicians are at the opposite end of the scale: whereas MPs link their marital failings to excessive time at work, teachers might link theirs to excessive time away from it.

If a teacher has a partner who is also a teacher, then foreign adventures may well be possible for a while. Should they start breeding, however, their prospects change dramatically. As most teachers will con- firm, once a teacher's salary has to accom- modate minors, even with another teacher's salary coming in, there will be lit- tle left over. School 'holidays' then become a grotesque misnomer, dominated by windswept caravans in west Wales, torpid visits to just-off-the-motorway theme parks and, of course, ubiquitous infants. For teachers in this particular quagmire, the start of a new term is an unqualified relief.

If the concept of 'have chalk, will travel' is illusory, what of the other supposed attraction of long summer holidays, viz., creative activity?

Certainly, many teachers have entered the profession earnestly believing that long holidays will allow them to write a best-sell- ing novel, pen some mind-bending poetry, or (at the very least) construct a state-of- the-art textbook. Again, very few succeed. This should come as no surprise, because even if teachers start out with creative tal- ent, the grinding rhythms of teaching will eventually knock it out of them.

This was painfully discovered by a col- league of mine who, until he became a teacher, was a promising historian. He had always planned to use his summer holidays to write a seminal account of the War of Jenkins's Ear, but was always prevented from doing so — he thought — by the demands of his small children. After 20 years in the job, though, his children have departed, enabling him to put his summer holidays to desired effect.

The results were dismal. He quickly dis- covered that, even if he once understood the War of Jenkins's Ear, he was complete- ly baffled by it now. To make matters worse, he had also forgotten how to write scholarly prose and could not concentrate for more than 30 seconds at a time: three decades of compulsory academic vandal- ism, of having to debase his subject with crude simplifications and fatuous 'tests' (like helping his GCSE students to `empathise' with Russian peasants) had clearly taken a heavy mental toll. When I last saw him, he was drinking alone in cen- tral Manchester, telling stories about Pitt the Younger to a bemused barmaid, while getting jostled by regulars contemptuous of his swotty demeanour. By his own admis- sion, he was well on the way to becoming either a drop-out or an Ofsted inspector.

So if the government does reduce the length of teachers' summer holidays, we should give it our full support. If nothing else, it would excise all those teachers who only hang on for a 'perk' which, in reality, does them no good at all. Teaching would then be limited to the truly committed and seriously talented; it would at last become a respected profession. Unfortunately there would be very few people left in it.

The author teaches at Manchester Grammar School and is editor of Changing Party Poli- cy in Britain.

Previous page

Previous page