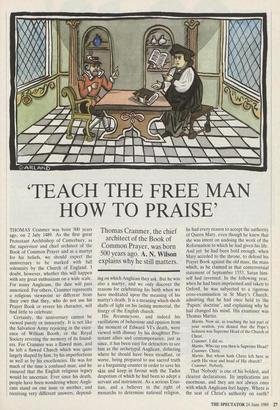

`TEACH THE FREE MAN HOW TO PRAISE'

THOMAS Cranmer was born 500 years ago, on 2 July 1489. As the first great Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury, as the supervisor and chief architect of the Book of Common Prayer and as a martyr for his beliefs, we should expect the anniversary to be marked with full solemnity by the Church of England. I doubt, however, whether this will happen with any great enthusiasm on a wide scale. For many Anglicans, the date will pass unnoticed. For others, Cranmer represents a religious viewpoint so different from their own that they, who do not use his Prayer Book or revere his character, will find little to celebrate.

Certainly, the anniversary cannot be viewed purely or innocently. It is not like the Salvation Army rejoicing in the exist- ence of William Booth, or the Royal Society revering the memory of its found- ers. For Cranmer was a flawed man, and he left a flawed Church which was quite largely shaped by him, by his imperfections as well as by his excellencies. He was for much of the time a confused man, and he ensured that the English religious legacy would be uncertain. Ever since his death, people have been wondering where Angli- cans stand on one issue or another, and receiving very different answers, depend-

Thomas Cranmer, the chief architect of the Book of Common Prayer, was born 500 years ago. A. N. Wilson explains why he still matters.

ing on which Anglican they ask. But he was also a martyr, and we only discover the reasons for celebrating his birth when we have meditated upon the meaning of his martyr's death. It is a meaning which sheds shafts of light on his lasting memorial, the liturgy of the English church.

His Recantacyons, and indeed his vacillations of behaviour and opinion from the moment of Edward VI's death, were viewed with dismay by his doughtier Pro- testant allies and contemporaries; just as since, it has been easy for detractors to see him as the archetypal Anglican, dithering where he should have been steadfast, or worse, being prepared to use sacred truth as a bargaining counter in order to save his skin and keep in favour with the Tudor despotism of which he had been so adept a servant and instrument. As a serious Eras- tian, and a believer in the right of monarchs to determine national religion, he had every reason to accept the authority of Queen Mary, even though he knew that she was intent on undoing the work of the Reformation to which he had given his life. And yet he had been bold enough, when Mary acceded to the throne,•to defend his Prayer Book against the old mass, the mass which, as he claimed in that controversial statement of September 1553, Satan him- self had invented. In the following year, when he had been imprisoned and taken to Oxford, he was subjected to a rigorous cross-examination in St Mary's Church, admitting that he had once held to the `Papists' doctrine', and explaining why he had changed his mind. His examiner was Thomas Martin.

Martin. Now sir, as touching the last part of your oration, you denied that the Pope's holiness was Supreme Head of the Church of Christ.

Cranmer. I did so.

Martin. Who say you then is Supreme Head? Cranmer. Christ.

Martin. But whom hath Christ left here in earth His vicar and head of His church? Cranmer. Nobody.

That 'Nobody' is one of his boldest, and clearest declarations. Its implications are enormous, and they are not always ones with which Anglicans feel happy. Where is the seat of Christ's authority on earth? Who exercises it? Nobody! Some Angli- cans, particularly those shaped by the traditions of the Tractarian revival, have always edged away from this stark view, dreaming of the day when Christ's Vicar in Rome would one day welcome back the erring children whom Cranmer rescued from his sway. For, without some such idea of revelation and authority, we are left alone: alone with the Bible, perhaps, and alone with God, but alone, and the Church is no more than a gathering together of alone people, flawed and fallen like Cran- mer himself. Much of the Anglican dilem- ma is contained in this position, and Cranmer was wise and honest enough to say that this was the true state of human beings. His rejection of the Pope is every bit as heroic and absolute as that of the figure who stands before the Grand In- quisitor in Dostoievsky's legend. Mystery, miracle and authority are rejected. Cran- mer, himself a man of his age, himself capable of burning heretics — one of his victims was a poor demented woman called Jane Bocher who did not believe in the humanity of Christ — is discernible here as one of the first modern men, discarding make-believe in favour of the risk of being alone, the risk of making up our own minds about how life should be followed, the risk of being wrong; without such a risk, Cranmer's death says, true religion is impossible.

His rejection of the doctrine of Transub- stantiation derives from the same doggedly honest attempt to tell the truth before God. It is a rejection of magic in favour of religion. If the substance of the bread had changed, as he argued at his examination, it must have changed forever: and then, what of its fate as, like other foods, it passed through the body? The presence of Christ in the Sacrament was to be under- stood in less chemical, less crudely mater- ialist, terms. So, too, was the presence of God in the world. And this, again, shows Cranmer to be truly modern, anticipating, in his eucharistic views, a whole view of God and man with which the human race would one day have to come to terms. God is not our ultimate magic. 'The world is that which is the case,' and it cannot be changed by the formulas of a liturgy or the incantations of a hierophant. We must accept the unchanging, and cruel, and indifferent world of Nature in which we live, and we cannot change it by words or wishes or even by prayers. God, if He is found or seen, can only be true if He remains God, and not a creature, to be made, or summoned to the altar of the church by an arcane rite. There is dogged- ness, realism, and risk here: the risk of deciding that, after all, there is no God or that He is unapproachable. Cranmer laid the foundations for such thoughts.

Not that he had them himself. His six Recantacyons make sad reading. During the last year of his life he appeared to be willing to commit the ultimate act of intellectual cowardice, to say that he be- lieved other than he did. It would be unfair, though, to say that he did so merely as an act of political expediency. He spent hours and weeks debating these questions in private conversations with the students of Christ Church, Oxford. There is every evidence that, knowing how momentous such ideas were, he had genuine doubts and misgivings. He and his generation were setting themselves up against the received wisdom of the Western Church, and he was not arrogant enough to be certain, all of the time, that he was right. He had a keen piety. It was the fire of Hell which he dreaded, and not the fires of his persecutors. Indeed, after the hideous deaths of Ridley and Latimer, which Cran- mer was compelled to witness, his heart was hardened against Catholicism. It was only in later months that he vacillated.

The vacillations ceased when it became clear that, contrary to all precedent, the authorities were to continue with his burn- ing even though he had forsworn his supposed heresy. In normal circumstances, if a heretic recanted his errors, he was regarded as redeemed, and did not need the purgation of fire. Cranmer was burnt out of spite, and not for reasons of reli- gious zeal. It was a brave death. His captors had read and approved his grovell- ing speech of apology, to be declaimed before they set light to the faggots. They did not know that he had concealed in his breast an alternative version, which he had sat up to write on the last night of his life.

And now I come to the great thing which so much troubleth my conscience, more than any thing that ever I did or said in my whole life. And that is the setting abroad of a writing contrary to the truth; which now here I renounce and refuse as things written with my hand contrary to the truth which I thought in my heart, and to save my life if it might be. . . . And forasmuch as my hand offended, writing contrary to my heart, my hand shall first be punished therefor; for, may I come to the fire, it shall be first burned. . . .

The image of this man, old by the

5Woht, ba9lia.Z4

standards of that period (67 years), standing with his hand in the flame and not uttering a cry is one of the most potent in the whole intellectual history of Western Europe, and it is all the more powerful in that Cranmer was not a dogged unchanging man, but a thoughtful vacillating character who was intelligent enough to know the difficulties of arriving at the truth. His last words, which scandalised those Catholics who killed him, were, 'I see Heaven open and Jesus on the right hand of God.'

The hand which was to perish in the flames had written the Prayer Books of 1549 and 1552 — or been chiefly responsi- ble for their compilation. Those who have written about Cranmer have sometimes done so in the spirit of W. H. Auden, in his poem of elegy for Yeats, as one whom Time will pardon for writing well. The defenders of the beleaguered 1662 book (so largely based on Cranmer's books) lay understandable stress upon its beauty. Cranmer would not thank us for a purely aesthetic appreciation of his work. True, he had the gift, so sadly denied the authors of more recent liturgies, the genius for writing prose which could bear endless public repetition; a genius for the phrase which can enter the bloodstream, remain- ing part of the imaginative life of the hearer for ever. 'We are not worthy so much as to gather up the crumbs under Thy table.' ... 'Create and make in us new and contrite hearts.' . . . `To pass our time in rest and quietness' . . . 'that so among the sundry and manifold changes of the world, our hearts may surely there be fixed where true joys are to be found'. Those who know Cranmer's book by heart have an incomparable storehouse which shapes and patterns life. But it is not just 'poetry'. Cranmer's liturgies, and occasional ser- vices and collects, have had such an ex- traordinary staying power because they do represent the human experience. His book enshrines a religion which is deeply rooted in life as it is actually experienced by men and women with 'unruly wills and affec- tions', who have left undone the things they ought to have done, and have done the things they ought not to have done, and who reach out to God in the knowledge. that there is no magic formula which will change human sinfulness or the relentless march of death. No Christian liturgy is less babyish, or less florid. The funeral service, for example, only consoles by truthfulness, by confronting death head on, and thank- ing God for delivering 'this our brother out of the miseries of this sinful world'. The fate of the soul, for which requiem masses pleaded, is left to the wisdom of God. Similarly, the preface to the marriage ceremony, and the phrases within it to which modern puritans have taken excep- tion — they are excised from the new books — are written for real human beings, tempted to fornication, but who can distinguish between satisfying lust 'like brute beasts' and wanting to say to some- one, 'with my body I thee worship'.

The sinfulness of the human race is something which Cranmer took, for gran- ted, and no one has ever held him, up as a model of sanctity. He knew about unruly wills and affections. His early academic career was ruined by a precipi- tate and youthful marriage. His second marriage, after he had taken orders, would appear to have been both a love match and a meeting of minds, since Margaret Cran- mer was a German, and Cranmer, by tortuous and circuitous steps, genuinely came to believe in the central tenets of Continental Protestantism. Central to this teaching is the doctrine of justification by faith only, and a certainty that the human race cannot redeem itself, nor partake in the work of redemption. When, in the Communion Service, it states that the burden of human sin is intolerable, a central view of nature itself is being ex- pounded. Modern egotism might make the unthinking reader of the phrase suppose that Cranmer was encouraging a guilt- ridden neurosis. When, however, we state that the burden of our sins is intolerable, we are not saying that we cannot bear a particular feeling. We are stating a theolo- gical belief. Sin itself cannot be borne, or paid off, or cancelled, by human desire or by religious observance. For those who found their own sins 'intolerable' in the modern sense, Cranmer left the provision of auricular confession by a penitent, that 'he may receive the benefit of absolution, together with ghostly counsel and advice to the quieting of his conscience'. So much for sins. But sin itself was, for Cranmer, the great and unalterable fact of human life, which had been borne by one means only, the 'full, perfect and sufficient sacrifice, oblation and satisfaction' of Calvary.

This is the core of the Prayer Book faith, Cranmer's faith, for which he died. No such uncompromising view survives in the confession of sin in the newer liturgy of the Alternative Service Book. There is no statement there that the burden of sin is intolerable, and no vast or cosmic hope that our muttered imperfections, commit- ted, we concede, 'through negligence, through weakness, through our own de- liberate fault' have received or needed the pardon of sacrificial love.

It was inevitable that Cranmer's Prayer Book would be superseded in the 20th century, not merely because so many Anglicans had become quasi-Roman Catholics, but because the world which the book represents had changed so utterly. It presupposes a renaissance world of 'Christ- ian kings, princes and governors'. Much of the language of the Visitation for the Sick or the Churching of Women could not be uttered by 20th-century human beings without an element of play-acting. The collects for Fair Weather, and Plenty, and Thanksgivings for Restoring Publick Peace at Home seem merely quaint, and in the present intellectual climate which applauds 'nter-faith dialogue, imams and rabbis sitting down with bishops to thrash out their supposed common ground, liberal Christians could not say the third collect for Good Friday without a blush. But though it would be surprising if a book had not dated in 440 years, it is surprising how much of it remains fresh and contempor- ary, and how much of it is a serious source of religious nourishment. And this is not just because it is full of 'lovely phrases'. It is because it grows out of the attempts by the reformers to arrive at the truth and to live by it. That mellifluous ex-Anglican, Newman, defined a gentleman as 'one who never inflicts pain'. It is hard to spell out Cranmer's achievement, and his glory, without giving pain to Newman's co- religionists. Better than anyone, Cranmer the politician and servant of Henry VIII knew that the Church of England had very shady origins. But the Reformation itself was not forged solely by politicians. It grew out of intellectual sincerity, hard thinking, deep reading, and it was ultimately bap- tised by Blood and Fire. Auden's elegy on Yeats, to which I alluded earlier, provides the perfect epitaph for Cranmer, whose struggling, honest and uncertain mind ge- nuinely believed that the human race should not be in the thrall of a spiritual dictatorship of human origins. For more than 400 years, English-speaking people have repeated the offices and services which Cranmer originally compiled. We should revere him.

In the deserts of the heart Let the healing fountain start, In the prison of his days Teach the free man how to praise.

That is precisely what Cranmer did in his life, in his death, and in his book.

Previous page

Previous page