Just as English as beefsteak

James Teacher

The recent publishing of Can You Forgive Her?, Phineas Finn, Ayala's Angel and Dr Wortle's School marks the first steps of the Trollope Society's heroic ven- ture to publish the entire oeuvre — some 48 novels in all — of the great Victorian author. The driving force behind 'this last obvious unclaimed peak in English pub- lishing' is John Letts, former joint prop- rietor of the Folio Society and now chair- man of the Trollope Society.

There have been many editions of the more popular Trollope novels. Most of the Barchester stories have run to at least 30 separate issues and The Warden must have topped 50 by now. The casual reader is already well-served: the Trollope Society edition is for the avid Trollopean.

The Trollope and Folio Societies jointly produce the editorial and introduction, the Folio Society attends to the setting, the two editions then diverge, the Folio Society adding modern illustrations and a rather gaudy cover while the Trollope Society uses the original illustrations and sombre (some would say too sombre) buckram, reminiscent of the shabby gentility of one of the author's less prosperous heroines. It is apparent that financial constraints have dictated the order of publishing. This is a pity, as the decision, though understand- able, has denied the Trollopean pundit the one opportunity of reading the novels in chronological order and hence appreciat- ing the development of the author's crea- tive art. It would have been a pleasant gesture, given the random appearance of the books, to fulfill one of Trollope's wishes, 'Who will read Can You Forgive Her?, Phineas Finn, Phineas Redux, and The Prime Minister consecutively, in order that he may understand the characters of the Duke of Omnium, of Plantagenet Palliser and Lady Glencora? Who will ever know that they should be so read?' Who, indeed?

The books are thoughtfully produced. The print size is generous enough to account for the passing years and should enable our fading eyesight to grapple with An Old Man's Love as we enter the second millennium. Many of Trollope's books were published in monthly parts, following a precedent set by Dickens and Thackeray. A leaf from the Penguin English Library edition should have been taken in the use of asterisks to denote the end of each monthly section. Notes, too, would have been welcome. Topical allusions to create an illusion of reality need to be understood and are particularly important in the poli- tical novels. One instance will suffice. To emphasise Lady Glencora's position in society Trollope describes her as having `property worth not less than fifty thousand a year'. The nuance would not have been lost on contemporary readers (as it is on us), for only a few months before the publication of Can You Forgive Her?, par- liament voted in 1863 an income of £50,000 a year to the Prince of Wales on his marriage.

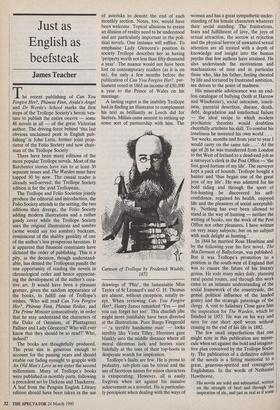

A lasting regret is the inability Trollope had in finding an illustrator to complement his text as brilliantly as Leech did for Surtees. Millais came nearest to striking up some sort of partnership with him. The Cartoon of Trollope by Frederick Waddy, 1872 drawings of 'Phiz', the lamentable Miss Taylor of St Leonard's and G. H. Thomas are almost, without exception, totally in- ept. When reviewing Can You Forgive Her?, Henry James remarked 'Yes — and you can forget her too'. This churlish jibe might more justifiably have been directed at the illustrations. Poor Burgo Fitzgerald — 'a terribly handsome man' — looks terribly like Vesta Tilley. Heroines gaze blankly into the middle distance where all moral dilemmas lurk and heroes stare balefully at the toes of their top-boots in desperate search for inspiration.

Trollope's faults are few. He is prone to pedantry, sub-plots can be trivial and the use of facetious names for minor characters is exasperating. However, all is easily forgiven when set against his massive achievement as a novelist. He is particular- ly percipient when dealing with the ways of women and has a great sympathetic under- standing of his female characters whatever their social standing. The frustrations, fears and fulfillment of love, the joys of sexual attraction, the sorrow at rejection and the physical horror of unwanted sexual attention are all treated with a depth of knowledge and insight into the human psyche that few authors have attained. He also understands the motivations and machinations of men and in particular those who, like his father, feeling cheated by life and tortured by frustrated ambition, are driven to the point of madness.

His miserable adolescence was an end- less catalogue of bullying (both at Harrow and Winchester), social ostracism, loneli- ness, parental desertion, disease, death, debt, degradation and intellectual failure — the ideal recipe to which modern psychiatric theorists would doubtless cheerfully attribute his skill. To combat his loneliness he invented his own world . . `for weeks, months and from year to year I would carry on the same tale ....' At the age of 26 he was transferred from London to the West of Ireland to a dead-end job as a surveyor's clerk in the Post Office 'the first good fortune of my life'. The surveyor kept a pack of hounds. Trollope bought a hunter and 'thus began one of the great joys of my life'. He was admired for his bold riding and through the sport of fox-hunting he discovered his self- confidence, regained his health, enjoyed life and the pleasures of social acceptabil- ity. 'Nothing has ever been allowed to stand in the way of hunting — neither the writing of books, nor the work of the Post Office nor other pleasures. I have written on very many subjects; but on no subject with such delight as hunting.'

In 1844 he married Rose Heseltine and by the following year his first novel, The MacDermots of Ballycloran, was published. But it was Trollope's promotion to a position in the south-west of England that was to ensure the future of his literary genius. He rode many miles daily, planning rural postal routes, and through this work came to an intimate understanding of the social framework of the countryside, the genial political influence of the landed gentry and the strategic patronage of the clergy. A visit to Salisbury Close gave him the inspiration for The Warden, which he finished in 1853. He was on his way and save for one short spell wrote without ceasing to the end of his life in 1882.

The few small imperfections that one might note in this publication are minus- cule when set against the bold and imagina- tive plan conceived by the Trollope Socie- ty. The publication of a definitive edition of the novels is a fitting memorial to a great, generous-spirited and courageous Englishman. In the words of Nathaniel Hawthorne,

His novels are solid and substantial, written on the strength of beef and through the inspiration of ale, and just as real as if some giant had hewn a great lump out of the earth, and put it under a glass case, with all its inhabitants going about their daily business, and not suspecting that they were being made a show of. And these books are just as English as beefsteak.

As Lady Albury remarked to Ayala of Sir Thomas Tringle, so do we of Anthony Trollope — 'My word, he is magnificent!'

Previous page

Previous page