PLUM JOB

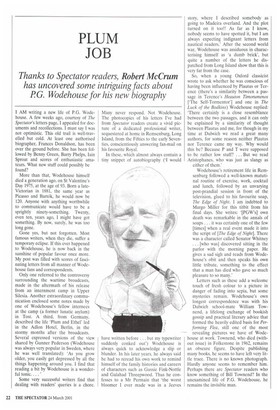

Thanks to Spectator readers, Robert McCrum

has uncovered some intriguing facts about PG. Wodehouse for his new biography

I AM writing a new life of P.G. Wodehouse. A few weeks ago, courtesy of The Spectator's letters page, I appealed for doc uments and recollections. I must say I was not optimistic. This old trail is well-trav elled but cold. At least one authorised biographer, Frances Donaldson, has been over the ground before. She has been fol lowed by Benny Green, Barry Phelps, lain Sproat and scores of enthusiastic amateurs. What new stuff could possibly be found?

More than that, Wodehouse himself died a generation ago, on St Valentine's Day 1975, at the age of 93. Born a lateVictorian in 1881, the same year as Picasso and Bartok, he would now be 120. Anyone with anything worthwhile to communicate would have to be a sprightly ninety-something. Twenty, even ten, years ago, I might have got something. By now, surely, he was too long gone.

Gone yes, but not forgotten. Most famous writers, when they die, suffer a temporary eclipse. If this ever happened to Wodehouse, he is now back in the sunshine of popular favour once more. My post was filled with scores of fascinating letters from all manner of Wodehouse fans and correspondents.

Only one referred to the controversy surrounding the wartime broadcasts, made in the aftermath of his release from an internment camp in Upper Silesia. Another extraordinary communication enclosed some notes made by one of Wodehouse's fellow internees at the camp (a former lunatic asylum) in Test. A third, from Germany, described the life 'Plum and Ethel' led in the Adlon Hotel, Berlin, in the stormy months after the broadcasts.

Several expressed versions of the view shared by Gunner Pederson (Wodehouse was always very popular in Sweden, where he was well translated): 'As you grow older, you easily get depressed by all the things happening around you. I find that reading a bit by Wodehouse is a wonderful tonic. Many never respond. Not Wodehouse. The photocopies of his letters I've had from Spectator readers create a vivid picture of a dedicated professional writer, sequestered at home in Remsenburg, Long Island, from the Fifties to the early Seventies, conscientiously answering fan-mail on his favourite Royal.

In these, which almost always contain a tiny snippet of autobiography CI would

have written before . . . but my typewriter suddenly conked out') Wodehouse is always quick to acknowledge a slip or blunder. In his later years, he always said he had to reread his own work to remind himself of the family histories and careers of characters such as Gussie Fink-Nottle and Galahad Threepwood. Thus he confesses to a Mr Permain that 'the worst bloomer I ever made was in a Jeeves story, where I described somebody as going to Madeira overland. And the plot turned on it too!! As far as I know, nobody seems to have spotted it, but I am always expecting indignant letters from nautical readers.' After the second world war, Wodehouse was assiduous in characterising himself as 'a dumb brick', but quite a number of the letters he dispatched from Long Island show that this is very far from the case.

So, when a young Oxford classicist wrote to ask whether he was conscious of having been influenced by Plautus or Terence (there's a similarity between a passage in Terence's Heauton Timorumenos ['The Self-Tormentor'] and one in The Luck of the Bodkins) Wodehouse replied: 'There certainly is a close resemblance between the two passages, and it can only be explained by a similarity of thought between Plautus and me, for though in my time at Dulwich we read a great many authors, for some reason neither Plautus nor Terence came my way. Why would this be? Because P and T were supposed to be rather low stuff? . . But we read Aristophanes, who was just as slangy as

either of them.'

Wodehouse's retirement life in Remsenburg followed a well-known matutinal routine of exercise, work, cocktail and lunch, followed by an unvarying post-prandial session in front of the television, glued to his favourite soap, The Edge of Night. I am indebted to Margo Miller for this titbit from his final days. She writes: JPGW's] own death was remarkable in the annals of soaps . . it was certainly one of the few [times] when a real event made it into the script of [The Edge of Night]. There was a character called Senator Whitney . [who was] discovered sitting in the parlor with the morning paper. He gives a sad sigh and reads from Wodehouse's obit and then speaks his own little tribute, something to the effect that a man has died who gave so much pleasure to so many.'

Letters such as these add a welcome touch of fresh colour to a picture in danger of fading into sepia, but some mysteries remain. Wodehouse's own longest correspondence was with his Dulwich school-mate William Tow nend, a lifelong exchange of bookish gossip and practical literary advice that

formed the heavily edited basis for Per

forming Flea, still one of the most revealing pictures we have of Wodehouse at work. Townend, who died (without issue) in Folkestone in 1962, remains an obscure figure. Despite publishing many books, he seems to have left very little trace. There is no known photograph. Hardly anyone seems to remember him. Perhaps there are Spectator readers who know something of Bill Townend? In the unexamined life of P.G. Wodehouse, he remains the invisible man.

Previous page

Previous page