PLAYING WITH THE CASINO'S MONEY

John Mortimer talks to Norman Tebbit, a hard nut

with a soft centre, who is pressing on with his uncompromising approach while there is still time

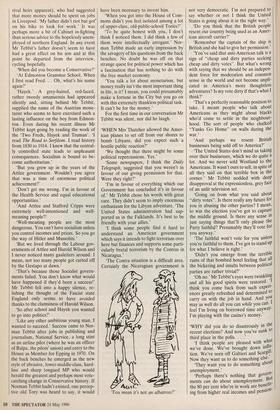

A VISIT to Norman Tebbit arouses ex- cited expectations. Should you take a long spoon, a bulb of garlic, or two twigs roughly bound into a cross? He has been variously described as a 'semi-house trained polecat' (Michael Foot), 'the Chingford Skinhead' (a Labour MP) and, since he acquired a cottage in Devon, 'The Hound of the Baskervilles'. Would he arise creakingly from a coffin in the basement of Smith Square in a crumpled suit of tails and a scarlet-lined opera cloak? Eager for the green limelight and the sound hissing from the wings I hurried down the backstreets of Westminster.

There was no smell of sulphur in the Conserva- tive Central Office, only the flags of the United Kingdom, a bust of Win- ston Churchill wearing his siren suit, large helpful girls hurrying back from lunch and a gentle, grey- haired man talking about his retirement. 'We have this big labrador dog and I think I'll devote my time to him.' And then, after a longish wait, I was ushered into the presence of the man whom the Financial Times could best describe as an enig- ma. If this were true I had only 45 minutes of the Chairman's time to find any sort of solution.

`My father was in the retail trade when I was born in the Thirties.' Mr Tebbit touched lightly on the story of his life. Which had the most influence on me, my mother or my father? Heavens only knows. I don't think either of them had! I think I had more influence on them. Were they Conservative? I don't think I ever asked. They weren't particularly religious. I don't think God ever came into my upbringing at all.'

`You've been very close to death at least twice.'

`My wife reckons I come close to death every time I drive a car, but I've got no convictions yet. Do go on.' `Once when you were strapped into the cockpit of a burning Mosquito during your National Service and you had to break open the canopy to escape. Another, of course, at the time of the Brighton hotel bombing. Did you feel you came close to God on either of those occasions?'

`I would have to say, quite honestly, that I haven't met Him yet.'

`Did you learn anything about death itself?'

`I can't tell you that I saw it as a gateway to pleasure.'

`You wouldn't describe yourself as a religious man?' `Well, I'm not an athesist. But Christ being the Son of God and so on. . .? No. I can't believe that. But I do think there's a system of order in the universe.' `So God's a paid up member of the Conservative Party?'

`Oh, yes. Of course.' And the suppress- ed laughter which had been bubbling away behind Mr Tebbit's surprising answers was released like a jet of steam. 'I've never had the slightest doubt about that. After all, he couldn't be a socialist.'

`Why not?'

`Because of the process of evolution.' `Tell me.' `Well, as I've playfully pointed out, evolution meant getting rid of the dino- saurs and replacing them with some more efficient and up-to-date animals. Any socialist would have been dedicated to protecting the dinosaurs in the name of compassion or conservation or something. The dinosaurs would never have been allowed to go. So God can't be a socialist.'

`You mean to say that there aren't any dinosaurs in the Tory Pary?'

`Of course there are.' Mr Tebbit was laughing openly now, almost blowing the lid off the kettle. 'And they've got to be got rid of too!'

`This father of yours. When did he actually get on his bike?'

`In the Thirties. He'd lost his job as a shop manager and he went off round the building sites.'

`Round Edmonton?'

`He was looking for casual labour.'

I remembered that Mr Tebbit had made his famous remark as a riposte to Michael Heseltine (when they were shaping up as rival heirs apparent), who had suggested that more money should be spent on jobs in Liverpool. 'My father didn't riot but got' on his bike to look for work.' It was perhaps more a bit of Cabinet in-fighting than serious advice to the hopelessly unem- ployed of northern England. In any event Mr Tebbit's father doesn't seem to have had a great effect on his son and at this point he departed from the interview, cycling hopefully.

`When did you become a Conservative?'

`At Edmonton Grammar School. When I first read Fred. . . Oh, what's his name again?'

`Hayek.' A grey-haired, red-faced, rather tweedy amanuensis had appeared silently and, sitting behind Mr Tebbit, supplied the name of the Austrian mone- tarist who seems to have exercised such a lasting influence on the boy from Edmon- ton. Even during his recent illness Mr Tebbit kept going by reading the work of the 'Two Freds, Hayek and Truman'. 'I read The Road to Serfdom. I read history from 1830 to 1914. I knew that the central- ly controlled state leads to unpleasant consequences. Socialism is bound to be- come authoritarian.'

`But you grew up in the years of the Attlee government. Wouldn't you agree that was a time of enormous political achievement?'

`Don't get me wrong. I'm in favour of the Health Service and equal educational opportunities.'

`And Attlee and Stafford Cripps were extremely well-intentioned and well- meaning people?'

`Well-meaning people are the most dangerous. You can't have socialism unless you control incomes and prices. So you go the way of Hitler and Mussolini.'

`But we lived through the Labour gov- ernments of Attlee and Harold Wilson and I never noticed many gauleiters around. I mean, not too many people got carted off by the Gestapo at dawn.'

`That's because those Socialist govern- ments failed. You don't know what would have happened if they'd been a success!' Mr Tebbit fell into a happy silence, re- lishing the thought of the Fascist state England only seems to have avoided thanks to the clumsiness of Harold Wilson. `So after school and Hayek you wanted to go into politics?'

`Like any other ambitious young man, I wanted to succeed.' Success came to Nor- man Tebbit after jobs in publishing and journalism, National Service, a long stint as an airline pilot (where he was an officer of Balpa, the pilots' union) and entry to the House as Member for Epping in 1970. On the back benches he emerged as the new style of abrasive, lower-middle-class, hard- line and sharp tongued MP who would herald the greatest and perhaps most vote- catching change in Conservative history. If Norman Tebbit hadn't existed, one percep- tive old Tory was heard to say, it would have been necessary to invent him.

`When you got into the House of Com- mons didn't you feel isolated among a lot of upper-class, old-public-school Tories?'

`To be quite honest with you, I don't think I noticed them. I did think a few of them were intellectually arrogant.' Nor- man Tebbit made an early impression by the savagery of his questions from the back benches. No doubt he was off on that strange quest for political power which has a fascination that has nothing to do with the free market economy.

`You talk a lot about monetarism, but money really isn't the most important thing in life, is it? I mean, you could presumably make a fortune in the City but you go on with this extremely thankless political task. It can't be for the money.'

For the first time in our conversation Mr Tebbit was silent, nor did he laugh.

`WHEN Mrs Thatcher allowed the Amer- ican planes to set off from our shores to bomb Libyans, did you expect such a hostile public reaction?'

`We thought that there might be some political repercussions. Yes.'

`Some newspapers, I think the Daily Telegraph, suggested that you weren't in favour of our giving permission for that. Were they right?'

`I'm in favour of everything which our Government has concluded it's in favour of.' Mr Tebbit chose his words with great care. They didn't seem to imply enormous enthusiasm for the Libyan adventure. 'The United States administration had sup- ported us in the Falklands. It's best to be friendly with your allies.'

`I think some people find it hard to understand an American government which says it intends to fight terrorism over here but finances and supports some parti- cularly brutal terrorism by the Contras in Nicaragua.'

`The Contra situation is a difficult area. Certainly the Nicaraguan government is 'You mean its not an albatross?' not very democratic. I'm not prepared to say whether or not I think the United States is going about it in the right way.'

`Do you think that the British people resent our country being used as an Amer- ican aircraft carrier?'

`Remember the captain of the ship is British and she had to give her permission.'

`You've said that anti-American talk is a sign of "cheap and dirty parties seeking cheap and dirty votes". But what's wrong with saying that we should be an indepen- dent force for moderation and common sense in the world and not become impli- cated in America's more thoughtless adventures? Is my vote dirty if that's what I think?'

`That's a perfectly reasonable position to take. I meant people who talk about Americans as they might about blacks who'd come to settle in the neighbour- hood. The sort of people who chalked "Yanks Go Home" on walls during the war.'

`And perhaps we resent British businesses being sold off to America?'

`The United States don't mind us taking over their businesses, which we do quite a lot. And we never sold Westland to the Americans. It wasn't ours to sell, in spite of all they said on that terrible box in the corner.' Mr Tebbit nodded with deep disapproval at the expressionless, grey face of an unlit television set.

`Going on from what you said about "dirty votes". Is there really any future for you in abusing the other parties? I mean, to win the election you've got to capture the middle ground. Is there any sense in just saying things that'll only please the Party faithful? Presumably they'll vote for you anyway.'

`The faithful won't vote for you unless you're faithful to them. I've got to stand up for what I believe is right.' `Didn't you emerge from the terrible ruins of that bombed hotel feeling that all the bickering and insults between political parties are rather trivial?' `Oh no.' Mr Tebbit's eyes were twinkling and all his good spirits were restored. .1 think you come back from such experi- ences greatly refreshed and determined to carry on with the job in hand. And you may as well do all you can while you can. 1 feel I'm living on borrowed time anywaY. I'm playing with the casino's money.'

`WHY did you do so disastrously in the recent elections? And now you've sunk to third place in the polls. . . `I think people are pleased with what we've done. We've brought down infla- tion. We've seen off Galtieri and Scarg,111. Now they want us to do something else. 'They want you to do something about unemployment.' `Perhaps there's nothing that govern; ments can do about unemployment. the 80 per cent who're in work are benefit- ing from higher real incomes and pension' ers are benefiting from lower inflation.'

`You can't expect a man suddenly thrown out of work in Middlesborough to be much cheered up by the low rate of inflation.'

`Well, that's it. Our aims and objectives aren't being made clear to the public. Lower inflation should produce more jobs eventually, but they don't understand that.'

'Don't you think that people are quite willing to pay higher rates and taxes if it means proper education, less unemploy- ment and better public services?'

'I believe they want all those things without having to pay for them. They want their cake and they want to eat it.'

'But if they decide they'll pay for a better sort of cake. . • •' 'I don't think they've decided that. I think they agree with us about taxes but they're not clear what we mean to do next. And then there's the question of the Prime Minister herself. . .

Mrs Thatcher, in full colour, smiled down on us from a large gilt photograph frame on the wall. Surely Mr Tebbit wasn't going to suggest that she might be an election liability? 'It's a question of her leadership when our aims aren't clearly defined. When people understand what she's doing there's a good deal of admiration for her energy and resolution and persistence, even from those people who don't agree with her. Now there's a perception that we don't know where we're going so those same qualities don't seem so attractive.'

`Isn't there also the boredom factor?'

`What?'

`Eventually we get bored with our politi- cians. We feel they've gone on too long. We got bored with Macmillan and Harold Wilson who were enormously admired in their time.'

Tin not sure that people get bored. Journalists get bored. That's the trouble.' Is that true? Or does the great British talent for boredom save us, even more than the free market economy, from the perils of dictatorship? I had another ten minutes before the Conservative Party Chairman had to rush away and see to the Duchy of Lancaster, and the enigma was still unsolved. Does he, for instance, be- lieve his more extravagant opinions (that Labour Party government leads to dicta- torship or that other political parties are `dirty and cheap'), or has he, by his own choice of pungent words, come to convince himself? Both may be true; he has con- vinced himself therefore he truly believes. There's no reason to doubt his sincerity.

`YOU gave a Disraeli Lecture denouncing the Permissive Society. But surely there were some worthwhile reforms during the Roy Jenkins era. You wouldn't be in favour of us still imprisoning consenting homosexuals of full age, for instance?'

wouldn't imprison homosexuals as such, no.' What on earth did the 'as such' mean? For the first time Mr Tebbit sound- ed gloomy. Then he cheered up and went on. `Don't get me wrong. I'm not intoler- ant or prudish. I'm nothing like Mizz Short of the Labour Party who wants to ban Page Three of the Sun. I mean, you can't ban all the naked ladies in the National Gallery, so I suppose Mizz Short thinks that the upper classes should be allowed to gaze at them in the National Gallery, but the workers shouldn't see them in the Sun. Unless she's against all paintings and statues like Crom- well, Michael Foot's favourite dictator.'

`You also talked about a return to Victorian values, but the greatest Victo- rians, like Dickens, spent their time de- nouncing the injustice of Victorian society and the evils of uninhibited capitalism.'

`That's right! It's exactly what the Earl of Shaftesbury did. He was a Conservative MP. You see, the socialists talk a lot about compassion, but the Tories do something about it.' Mr Tebbit, having astutely snatched a party political point out of the horrors of Victorian England, found his cheerfulness quite restored.

'YOU don't give any recreations in Who's Who. Is that because you haven't got any?'

'Really because I regard my private life as private. It has been rumoured that I do a little gardening.' `What do you read?' `Mainly those horrible red boxes!'

'I'm afraid that in your case joining in the profit sharing of the state would mean that you paid us money.' 'Do you think you'll win the next elec- tion?'

'If we can desist from shooting ourselves in the foot. I'm opposed to us constantly doing that.'

'And what have you done with Jeffrey Archer?'

Although I had seen that ebullient au- thor's name on a door on the way up I thought that since he told the young unemployed that he solved all his problems with a best-seller he had been kept bound and gagged in the cellar.

'Jeffrey's doing a terrific job speaking to the faithful.'

`But he's not allowed to speak to the world at large?'

'Oh yes he is. We had him on Question Time.'

'Who do you admire on the Labour benches? I imagine you might have a bit of a soft spot for Dennis Skinner.' It was an appealing thought, a glimmer of fellow feeling for the `Beast of Bolsover' from the `Hound of the Baskervilles'.

'Yes. Except when he goes right over the top. The world needs a Dennis Skinner. I don't think the world needs a Hattersley.'

`Anyone else?'

`Oh, I'd hate to ruin their careers by naming them.'

My three-quarters of an hour had ticked away and Mr Tebbit was on his feet. I had time for one more question.

`If it became clear to you that by going on saying the things you've been saying you'd lose the next election, would you change them?'

'Of course not.' Mr Tebbit seemed only faintly amused by the suggestion. 'If the Conservatives wanted to change their poli- cies they'd have to find another Chairman. I have to be true to what I stand for. And I shall go on expressing myself robustly.'

Although he has come in for more than his share of political abuse many people have experienced Mr Tebbit's considerable charm, and he is said to have earned the devotion of his Civil Servants, despite his habit of listening to Test Match commen- taries during meetings. One MP called him a hard nut with a soft centre and even Mr Moss Evans, who Mr Tebbit would no doubt say is one of the 'cloth cap barons' of the trade union world, found him 'very scathing but without offence'. It seems clear that Mr Tebbit's particular brand of politics, by Friedrich von Hayek out of Edmonton County Grammar, is going out of style. Castigated by the electorate, the Conservative party is now anxious to de- monstrate its 'caring heart' and spend money, at least on education, which Mr Tebbit has called one of 'the soft issues'. He is probably too honest a man, and perhaps an insufficiently deft politician, to trim his sails to the prevailing wind. He may even feel, with one of his ironic little laughs, that he has, after all, nothing very much to lose. He is still playing with the casino's money.

Previous page

Previous page