ARTS

Exhibitions 1

Carved in stone

Giles Auty

Henry Moore

(Royal Academy, till 11 December)

Henry Moore this week at the Royal Academy, Francis Bacon next week at the Central House of the Artists in Moscow: yet again one faces the problem of putting these artists, whom many see as the most significant duo to emerge from Britain this century, into some kind of context. In the case of Bacon, I hope a degree of culture shock and the keen Moscow air may stir fresh critical insights. It will be interesting, too, to learn how Bacon's imagery appears

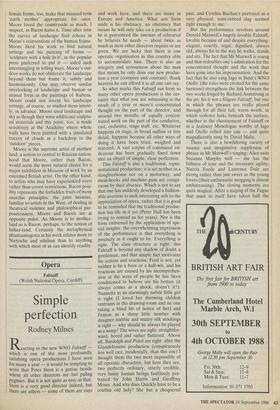

Sculptor of repose: Henry Moore's 'Girl with Clasped Hands', 1930 to those seeing it, for the first time, in all its fleshly palpability. Why are Russian artists so eager to see Bacon? I will do my best to find out.

Moore, at the Academy, presents a different kind of problem. So much has been written about the artist and so secure is his apparent status that one feels buried, not merely by the weighty monumentality of the works themselves, but under the unanimity of the reception afforded them. Thus it was intriguing to learn from Francis Bacon last year that he finds many of Moore's drawings 'grotesque'. Artists find it possible still to speak so of one another, at a time when most published artistic comment is characterised by reticence and timidity.

During this century in Britain, works which have been held to be modern sculp- ture — whatever their antecedents — have frequently provoked violent public reac- tion. Jacob Epstein was singled out for special vilification yet, like Moore, dis- turbed traditionalists more by his derived primitivism and references to other cul- tures than by purely modernistic reduc- tions or abstractions. By his early prefer- ence for carving over moulding, and em- ployment of tools whose use had been in decline since the Renaissance, Moore aligned himself with continuation and tradition much more than with modernistic schism; indeed, his forays into a more distilled modern language were few and relatively unsuccessful. Moore's stringed forms — an idiom continued by Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo, with greater success — look clumsy and uneasy. Whenever Moore departed, even tempor- arily, from his basic concerns, a feeling of nervousness enters the work. Moore is a sculptor of repose and immutability, not of movement. His stringed forms apart, I found his two warriors — 'with shield' and 'falling' — the least convincing works in the present historical survey at the Royal Academy. The idea of a warrior's male- ness, savagery and aggression seem outside the sculptor's expressive range. From cer- tain angles the head of 'Warrior with Shield' reminds me irresistibly of that of a small, climbing marsupial. For me, such occasional uncertainties make Moore more human and approachable. In this show there are more than enough magnificent pieces to convince, ranging from the early masks and stone pieces to the late, over- whelming bronzes. The exhibition format is chronological rather than thematic and the whole is helped by the re-staging of established settings. The wonderful Madonna and Child from the Church of St Matthew, Northampton, is shown, as it was meant to be, within a context of ecclesiastical architecture.

Moore's major, recurrent theme is that of the mother and child. His great reclining female forms, too, make that misused term `earth mother' appropriate for once. Moore loved the countryside as much, I suspect, as Bacon hates it. Time after time the curves of landscape find echoes in Moore's reinventions of the human frame. Moore liked his work to find natural settings and his piercing of forms 'sculpture with a hole in it', as the popular press preferred to put it — aided such intermingling in telling ways. Moore's out- door works do not obliterate the landscape beyond them but frame it, subtly and harmoniously. One may observe similar interlocking of landscape and human or animal form in the paintings of Rubens. Moore could not invent his landscape settings, of course, so studied them intent- ly, in advance. Moore used landscape and sky as though they were additional sculptu- ral materials and this point, too, is made sensitively at the Academy where whole walls have been painted with a simulated tracery of clouds as a backdrop to the `outdoor' pieces.

Moore is the supreme artist of mother/ land, a notion so central to Russian nation- hood that Moore, rather than Bacon, would seem the more natural choice for a major exhibition in Moscow of work by an esteemed British artist. On the other hand, to artists who may have experienced overt rather than covert restrictions, Bacon poss- ibly represents the forbidden fruits of more anarchic principles: the joint luxuries, familiar to artists in the West, of dealing in theatrical violence and philosophical pur- poselessness. Moore and Bacon are at opposite poles. As Moore is to mother- land so is Bacon, perhaps, to the notion of father-land. Certainly the metaphysical phantasmagoria in his work relates more to Nietzsche and nihilism than to anything with which most of us can identify readily.

Previous page

Previous page