Books

A hand-picked Lobbyman

Ferdinand Mount

The Abuse of Power James Margach (W. H. Allen £5.50)

There is something cosy about the idea of a 'Lobbyman'. Echoes of Lob-lie-by-the-fire,

Hobgoblin, Hobby-horse and Hobbit suggest a friendly, domestic, indoor spirit. Webster's and the Oxford English Dictionary do not acknowledge the existence of the word — which merely confirms the discretion of Lobbymen and their honourable reluctance to commit confidences to print. Only the unnameable are fit audience for the unsayable. Would Beckett and Wittgenstein have made good Lobbymen? The existence of a group of political journalists whose defining principle is discretion must be considered a paradox. The bargain by which the political reporter surrenders his birthright of unqualified candour in return for the privilege of access to the sacred hidden regions of Westminster belongs to the fairytale realm of devils' bargains. And nothing could be more paradoxical, not to say topsy-turvy, than this extraordinary book by Mr James Margach, for many years the Lobbyman (is the word his own invention?) of the Sunday Times.

Values seem to be curiously reversed in the Lobbyman's kingdom, conventional appearances magically turned upside down by the Palace goblins. For instance, I am told that some people in the outside world imagine us political journalists to be seedy, intemperate, scurrilous, prying creatures. We are of course nothing of the sort. Mr Margach points out that lobby correspondents are always 'distinguished', 'honourable', 'senior', 'outstanding', 'experienced', 'exceptionally able', 'penetrating and challenging' or even, in the case of E. P. Stacpoole ('Stacciet), 'that wonderful Press Association correspondent'. Lobbymen are loyal, discreet, charming and intelligent; they never let a pal down; and they stand up for truth and justice against the biggest bully. They do not simply do a job; they 'perform their professional duties'. Typical of the fraternity is the behaviour of a correspondent from a Sunday paper whom Harold Macmillan accused of writing nonsense and lies: 'The journalist concerned reacted quietly and with impressive dignity, refusing to be provoked into a public brawl with the Prime Minister and the experienced chairman rescued the situation by calmly intervening at a pause in Macmillan's tirade: "may we now proceed to ask some questions of the Prime Minister? first. . ." 'The possibility that the journalist under attack was just too scared to answer back is not to be entertained. The Lobbyman does not scare so easily. It must not be thought that Mr Margach, himself described by his publishers as 'the distinguished former Political Correspondent and doyen of the Lobby', confines his warm appreciation to Lobbymen. Employers too evoke his tribute: Lord Thomson has a 'folksy but always penetrating style which proved so endearing and disarming' and also 'a unique ability to tell the truth without causing offence'; Lord Kemsley persuades Churchill to retire by 'a subtle power-play'; Sir Denis, Hamilton is diplomatic, firm and 'without rancour'.

How pleasant it would be to linger in the company of such nonpareils. But, unfortunately, we and they must turn our attention to the objects of their professional duties, the politicians. Look here upon this picture, and on this. It is a Hyperionto-a-satyr situation. According to Mr Margach, in dealing with the press every modern Prime Minister except Attlee and Douglas-Home has been paranoiac, deceitful, vain, bullying, secretive, unscrupulous and vengeful. They have almost all been obsessed to the point of lunacy with Cabinet leaks and with absurdly improbable conspiracy theories. They have been willing to use personal smears, pressure on employers and visits from the Special Branch to silence or remove a troublesome reporter. They follow Lloyd George's motto: 'what you can't square, you squash; what you can't squash, you square.' At the beginning of Mr Margach's career the Special Branch grilled a Lobbyman for five hours about the source of a Cabinet leak at the behest of Rarnsay MacDonald. Forty years later Scotland Yard raided the offices of the Railway Gazette to discover how the Sunday Times had got hold of a government plan for the closure of the railway lines. Chamberlain ruthlessly manipulated the Lobby to promote appeasement and had the telephones of the anti-appeasement group tapped. Churchill very nearly had the Daily Mirror closed down. Eden continuously attempted to manipulate the press during Suez. In Macmillan's time, the 1922 Committee tried to bully The Times into sacking its political editor. As Chancellor, Jim Callaghan went so far as to brandish the Official Secrets Act in his efforts to stop publication of a Sunday Times series on the 1964 sterling crisis. Ted Heath was rude and secretive — although Margach does not claim that he attempted to manipulate. And Harold Wilson's obsessions with the press are legendary, revealing bile, spite and persecution mania on a scale which make President Nixon look positively preux chevalier. When Nora Beloff, that 'most experienced doyenne', pointed out the odd

nature of Wilson's kitchen Cabinet and the excessive influence of Marcia, the Prime Minister had her followed and even suggested that she slept with a minister in returnfor Cabinet leaks. Here be monsters.

This is splendid, savage, unrestrained stuff. In only 200 pages Mr Margach teaches us unforgettably that Prime Ministers never stop and never will stop trying an they can get away with to control, tame and silence the press. War is the natural state of relations between politicians and newspal,' ers. Danger lurks for the Lobbyman LII every intimate contact with politicians. Walter Lippmann pointed out that the danger to independence and integrity did not come from the pressures that might be put upon journalists; the danger was that they might be captivated by the company they kept. Hazlitt told editors to stay in their garrets. Margach himself tells us that 'over the years it was said that I saw too much of all Prime Ministers'.

Yet he scarcely pauses to ask himself whether this allegation might be true. Nor does he seriously consider whether the syn.' tern of off-the-record briefings, back grounders and still more arcane contacts between political journalists and politicians may not on balance be of more advantage to the politicians than to the public interest. How far is the Lobbyman's personal knoWledge of leading political figures embodied in his printed work? And to what extent is the extra value of this element outweighed by any tendency to soften his judgments or bowdlerise his descriptions out of consideration for his friendships or the hope of future confidences? Many stories are best covered by the combination of a specialist insider (who knows the characters involved) and a general reporter (who doesn't and can therefore not only ask the rude questions but also write down rude conclusions). Lobbymen, it must be said, are by no means the most amenable of specialist insiders; industrial and diplomatic correspondents are usually far more easilY suborned by contact with the great, which is why the great frequently prefer them as leak-channels.

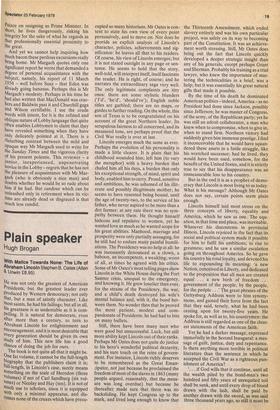

These delicate questions — in some degree challenging as they do the manner of his life's work — do not detain Mr Margach. He merely remarks that 'senior correspondents, whether in London, Washington, Paris or Bonn, are only doing their jobs properly if they see a great deal of Premiers, Presidents and Chancellors'. And he continues describing how he did in fact see a great deal of Prime Ministers. He sees Wilson every week with 'a few handpicked Lobbymen' who become known as 'the White Commonwealth'. He weekends with Wilson at Chequers. He sits in Douglas Home's flat amid playpens and scattered toys belonging to the Prime Minister's grandchildren. He has a long meeting with Macmillan at the Carlton Club. He belongs to Chamberlain's magic circle of UK Lobbymen. He is in the private sitting-room at No. 10 when MacDonald returns from the

Palace on resigning as Prime Minister. In Short, he lives dangerously, risking his integrity for the sake of what he regards as that professionally essential proximity to the great.

And yet we cannot help inquiring how much bacon these perilous excursions really bring home. Mr Margach quotes only one Significant report he wrote that demanded a degree of personal acquaintance with the subject, namely, his report of 11 March 1956 — well before Suez — that Eden was already going bananas. Perhaps this is Mr Margach's modesty. Perhaps in his time he had also written that MacDonald was crackers and Baldwin past it and Churchill gaga and Wilson certifiable. I use the crude words with intent, for it is the refined and Oblique nature of Lobby language that quite Often enables Lobbymen to claim that they have revealed something when they have only delicately pointed at it. There is a disturbing contrast between the mild and Opaque way Mr Margach used to write for the Sunday Times and the vigorous clarity Of his present polemic. This reviewer — a Junior, inexperienced, unpenetrating novice in the Lobby — regrets that he has not the pleasure of acquaintance with Mr Margach (who is obviously a nice man) and

doubts whether he would be so rude about him if he had. But candour which can be unleashed only in retirement when its victims are already dead or disgraced is that much less candid.

Previous page

Previous page