The chink in Russia's armour

Bohdan Nahaylo

Last Sunday's curt message of congratulations from President Brezhnev to Mr Stanislaw Kania on his re-election as Poland's party leader barely concealed the bitterness of the pill that Moscow has had to swallow. The Soviet leadership can hardly be pleased with the outcome of the Polish party congress — a meeting which it would have preferred not to have taken place at all. For the special congress of the Polish United Workers' Party was indeed 'extraordinary'. It saw the first genuinely democratic party elections in the Soviet bloc, the election by secret ballot of a largely new 200-strong Central Committee and 15-strong Politbureau which includes, remarkably enough, a member of the free trade union organisation Solidarity, and the personal triumph of Mr Kania, a leader pledged to continue the course of moderate reform and, as was only too apparent in recent weeks, hardly the Kremlin's choice.

As far as Moscow is concerned, the Polish ulcer, instead of showing signs of healing, continues to fester. Now, on top of everything else, a rejuvenated Polish Communist Party has emerged permeated with the same irrepressible spirit of 'odnowa', or Commitment to renewal, that has swept the country. Overnight, the unprecedented democratic voting procedure purged the party of most of its old guard and pushed Poland further past the point of no return. Significantly, the most rapturous ovation during the congress was given to the deputy premier and leading liberal, Mr Mieczyslaw Rakowski, who delivered an impassioned warning that any attempt to abandon reform would result in a blood bath. Not surprisingly, the Soviet media failed to report his speech, as it did, for that matter, the impressive display of internal party democracy at the congress. Shortly afterwards, however, without actually naming Mr Rakowski, lzvestia expressed concern that some of the speeches were 'revisionist'.

In recent months the Soviet media, while warning of 'creeping counter-revolution' in Poland, has at best been lukewarm in its attitude towards the Polish party's handling of the crisis. Towards the end of April, the Soviet leadership seems to have experienced a loss of confidence in the Polish party after Mikhail Suslov, the veteran Soviet Politbureau member responsible for ideological matters, returned from a brief visit to Warsaw. The Soviet press accused 'revisionist elements' in the Polish party of attempting 'to paralyse the party of Polish Communists' and thereby prevent it from carrying out its role 'as the leading force in society'. On 5 June, the growing anxiety with which Moscow viewed the Polish situation prompted the Soviet leaders to address a firm letter to the Polish Central Committee effectively stating that Moscow could only take so much and urging the Polish Communists to put their house in order. Although the likelihood of Soviet military intervention has receded since the end of last year, it cannot be entirely ruled out. Last week a Soviet Politbureau member, Viktor Grishin, reminded the delegates at the congress that the Soviet Union 'cannot be indifferent when the point at issue is the destiny of socialism in a fraternal socialist country. It is not a Soviet custom', he added, 'to abandon our friends and allies in the hour of need.'

No matter how distasteful the events of the last fortnight might seem, the Soviet leadership, short of resorting to 'fraternal' military intervention, has little choice but to learn to live with these further changes, and support, even if grudgingly, the new-look Polish party. For all its faults, this body is after all the Soviet Union's only real auxiliary in Poland through which it can hope to exert influence.

The major complication is that the party is one of several importance forces, and not the leading force in society. The three million party members form a small minority of Poland's population of 35 million. Solidarity — a genuine working class movement of mass proportions.— has around ten million members. The Catholic Church, of course, is even larger. The most serious shortcoming of the Polish party, Mr Grishin told the congress, has been that it — the 'vanguard of the working class' — has lost touch with the masses. Consequently, he was in full agreement with the Polish party leaders on the urgent need to 'restore the party's prestige in society and regain the people's trust'. It remains to be seen whether or not Mr Kania and his colleagues, for all their assurances to Moscow during the congress that Poland will not disappoint her socialist allies, will find a way of 'normalising' the situation to the satisfaction of the Soviet Union.

While the Soviet leadership maintains a wait-and-see attitude, it cannot ignore the possibility of contagion from Poland's protracted crisis. For many months now, Moscow has been responding preemptively to this challenge. The Soviet media has increased its coverage of issues in the area of trade union and workers' rights, including the exposure of corrupt officials and of wastage through bureaucratic inefficiency. At the 26th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party in February, President Leonid Brezhnev himself called for improvements in the work of Soviet trade unions. Shortly before the congress, in a highly unusual departure from longstanding practice, blue collar workers were elected to the bureaux of the Central Committees of five republican party organisations, in Lithuania and Latvia, and in Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaidzhan. Moreover, there has been no respite in the sustained assault on all forms of dissent launched at the end of 1979. What is particularly striking is both the large number of national rights compaigners arrested in the Baltic republics and in Ukraine — the western borderlands of the Soviet Union that are most vulnerable to influences from Poland — and the severe sentences of up to 15 years imprisonment that have been handed out.

Although the Soviet authorities have so far managed to prevent the outbreak of serious labour disturbances in the USSR, it is impossible for them hermetically to seal off the Soviet population from what is happening in Poland. Recently, a statement (addressed to the United Nations Human Rights Commission) from Mykola Pohyba, a Ukrainian worker from Kiev serving a five-year sentence ostensibly for hooliganism, arrived in the West, providing yet more evidence of the impact which events in Poland are having in the Soviet Union. In his letter, dated 4 November 1980, Pohyba writes: 'Recent events in Poland have clearly shown that the working class is capable of waging a struggle for its rights and freedoms, for a real improvement of its well-being, and that the efficacy of this struggle depends on the degree of solidarity of the working class and its level of self-organisation.' Further, in March and April of this year, three separate strikes are reported to have taken place in Kiev which resulted in the workers' demands promptly being met.

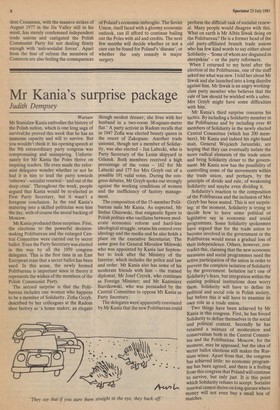

The Soviet Union's anxiety about Poland is shared by the leaders of other Soviet bloc states. The Czechoslovak and East German media have taken the lead in criticising their troublesome neighbour. In Rumania, Presi dent Ceausescu, with the massive strikes of August 1977 in the Jiu Valley still in his mind, has sternly condemned independent trade unions and castigated the Polish Communist Party for not dealing firmly enough with 'anti-socialist forces'. Apart from the fear of reform the members of Comecon are also feeling the consequences of Poland's economic imbroglio. The Soviet Union, itself faced with a gloomy economic outlook, can ill afford to continue bailing out the Poles with aid and credits. The next few months will decide whether or not a cure can be found for Poland's 'disease', or whether the only remedy is major surgery.

Previous page

Previous page