TRIDENTINE TRIBULATIONS

Rupert Scott reports on the latest rebellion of the traditionalist Archbishop Lefebvre Rome IT HAS been some years since the Italian anti-clerical press has enjoyed itself so much. The Lefebvre affair combines two of its favourite themes — the dangers of the submerged far Right and the erosion of Vatican power. The real fun came with descriptions of life at the principal semi- nary of Monsignor Lefebvre's Fraternite Sacerdotale Pio X at Econe in the Swiss Valais, from which, last week, he announced his imminent schism. They made it sound like an ecclesiastical Gor- donstoun, training party workers for Jean- Marie Le Pen — crew-cut seminarians in long black cassocks, rigorous discipline, floors licked clean in penance and all funded, it was suggested, by unnamed French aristocrats of fascist affiliation. Lefebvre, now the half-senile tool of Franco-admiring intransigeants, makes annual pilgrimages to the grave of Main. Econe is invariably described as a 'Swiss mountain bastion'. There has been nothing quite like it since P2 and the scandal of the Vatican Bank.

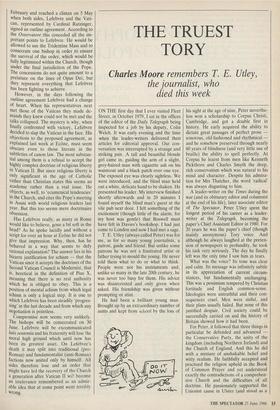

Ec6ne, I was surprised to discover when I went there last week, is in fact a modest collection of buildings at the top of the Rhone valley on a disappointingly unbas- tionlike site next to an electricity generat- ing plant. I scanned the walls of the seminary for signed photographs of Le Pen, perhaps even of Franco or Mussolini, but found nothing more suspicious than formal portraits of the most orthodox Popes of the 19th century. The hottest material was a flysheet of 'avis pratique' to Christians from the 82-year-old Monsignor prominently recommending 'abstinence de television et des livres d'une nature eroti- que'. The seminarists do wear long soutanes and their hair is rather short, but they look no more outlandish than models in Ralph Lauren ads or extras in a film by Louis Malle.

It recreates the atmosphere of a French seminary pre-Second Vatican Council. Ex- actly the type of seminary, of course, that Lefebvre attended in the 1920s. The lec- ture hall contains the works of St Thomas Aquinas and a map of the Apostolic Church. The emphasis is strongly Gallic and not a little puritan; perhaps Jansenist is a more appropriate description. But to extend the comparison between Econe and Port-Royal, the Jansenist headquarters suppressed by Louis XIV, would be a mistake. For Lefebvre's is not a movement distinguished by intellectual pretensions or political aims. It is certainly no threat to the established Church, merely a very orthodox, very old-fashioned seminary, efficiently training parish priests.

It is difficult, walking around the semi- nary and thinking about the order's his- tory, not to admire Monsignor Lefebvre. There is something remarkable about an ex-missionary bishop who at the age of 64 founded a religious order which within a decade was ordaining nearly as many priests every year as the entire Catholic Church in France. The Fraternity now operates seminaries in five countries. S. Nicholas en Chardonnet, its church in Paris, is packed every Sunday. Lefebvre, seeing the Church disintegrate around him in the 1960s, was prepared, unlike thousands of others who witnessed the same thing, to resist what he saw as the disastrous changes of the progressives and to champion his own convictions. The

Fraternity's first few years were heroic in every sense. Michael Davies's book Apolo- gia Pro Marcel Lefebvre catalogues his persecution, the word is no exaggeration, by Paul VI and the Bishop of Lausanne, a campaign now generally admitted to have been an unjust, foolish misuse of Vatican authority. It is the shadow over the Vati- can's actions in those years that has earned Lefebvre such strong, if usually passive, support not just among traditionalists but among liberal, bien pensant Catholics all over the world.

Yet while unquestionably courageous, there is a distressingly crass side to Lefeb- vre. He has a remarkable facility for making remarks in the worst taste at the wrong time, like his recent suggestion that the Vatican was infected with 'Aids of the mind'. He has an obsession, repeatedly stressed during his press conference last week, about homosexuality in seminaries. He once described the Pauline Mass as 'a bastard rite practised by bastard priests'. In Rome a few years ago he gave a press conference in the palazzo of a sympathetic (but notoriously right-wing) noblewoman in which he called the then utterly respect- able, highly intelligent Cardinal- Archbishop of Milan Carlo Colombo an 'abominable person'. Last year he told an Italian journalist from the magazine 30 Giorni that he greatly admired General Pinochet, who was 'a champion of tradi- tional Catholicism'. No remark could have been better designed to cause offence in Italy, where Pinochet sits next to President Botha.and Mr Shamir in the rogues gallery of liberal opinion.

Perhaps Lefebvre's most disastrous fail- ing is his absolute incomprehension of the subtleties of Vatican politics. Things have undoubtedly changed in Rome "since the 1970s. There are many cardinals in the Curia who are now prepared to admit that Paul VI's pontificate was the most dis- astrous of the century. Pope Wojtyla, if progressive in image, is highly orthodox in spirit. Far from wishing to persecute the Fraternite Sacerdotale Pio X, the Vatican has been for some time desperate to make peace. Pope John Paul wants to unify the right wing of the Church in order to concentrate on the far more worrying

problem of the left, in particular on the theologians like Hans Kfing in Germany, or Charles Curran in America, the corro- sive effects of whose radical theology are far more serious than the eccentricities of an octogenarian bishop at Econe.

But these changes have gone unnoticed by the Monsignor. At least this, or persecution mania, are the only plausible explanations for his behaviour in the last few months. Last Friday, following Lefeb- vre's announcement that he would conse- crate four new bishops without Papal authority, the Vatican published details of

the secret negotiations between itself and Lefebvre in its semi-official newspaper the Osservatore Romano. These began in

February and reached a climax on 5 May when both sides, Lefebvre and the Vati- can, represented by Cardinal Ratzinger,

signed an outline agreement. According to the Osservatore this conceded all the im-

portant points to Lefebvre. He would be allowed to use the Tridentine Mass and to consecrate one bishop in order to ensure the survival of the order, which would be fully legitimised within the Church, though under the final jurisdiction of the Pope. The concessions do not quite amount to a prelature on the lines of Opus Dei, but they represent everything that Lefebvre has been fighting to achieve. However, in the days following the outline agreement Lefebvre had a change of heart. When his representatives next met those of the Vatican they made de- mands they knew could not be met and the talks collapsed. The mystery is why, when finally confronted with victory, Lefebvre decided to slap the Vatican in the face. His objections to the proposed agreement, as explained last week at Ec6ne, must seem obscure even to those literate in the subtleties of canon law. The most substan- tial among them is a refusal to accept the highly complex doctrine of religious liberty in Vatican II. But since religious liberty is only significant in the age of Catholic rather than Christian states this seems an academic rather than a real issue. He objects, as well, to 'ecumenical tendencies' in the Church, and cites the Pope's meeting in Assisi with world religious leaders last year. But this too seems mere doctrinaire obsession.

Has Lefebvre really, as many in Rome would like to believe, gone a bit soft in the head? As he spoke lucidly and without a script for over an hour at Eel:111e he did not give that impression. Why, then, has he behaved in a way that seems to defy rational explanation? The answer lies in his bizarre justification for schism — that the Vatican since it accepts the doctrines of the Second Vatican Council is Modernist, that is, heretical in the definition of Pius X, meaning that there is no real authority which he is obliged to obey. This is a- position of mental schism from which legal schism is only a logical step. It is one to which Lefebvre has been steadily 'progres- sing' in the last decade and from which any negotiation is pointless.

Compromise now seems very unlikely. The bishops will be consecrated on 30 June. Lefebvre will be excommunicated latis sententia and his fraternity will lose the moral high ground which until now has been its greatest asset. On Lefebvre's death it may split into traditional (pro- Roman) and fundamentalist (anti-Roman) factions now united only by himself. All sides therefore lose and an order that might have led the recovery of the Church a generation after Vatican II will become an irrelevance remembered as an admir- able idea that at some point went terribly wrong.

Previous page

Previous page