SCENTS AND SENSIBILITY

Alexandra Artley predicts the

decline of aggressive synthetic perfumes

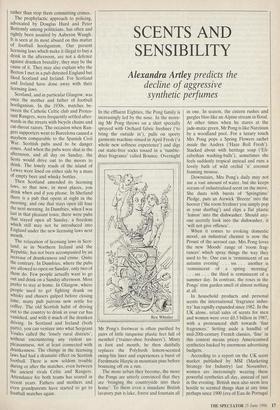

In the effluent Eighties, the Pong family is increasingly led by the nose. In the morn- ing Mr Pong throws on a shirt specially sprayed with Orchard fabric freshner ('to bring the outside in'), pulls on sporty garments machine-rinsed in April Fresh ('a whole new softness experience') and digs out static-free socks tossed in a 'tumble- drier fragrance' called Bounce. Overnight Mr Pong's footwear is often purified by pairs of little turquoise plastic feet full of menthol (grainer-shoe freshners'). Minty in foot and mouth, he then dutifully replaces the Polyfresh lemon-scented swing-bin liner and experiences a burst of Freshmatic Harpic in mountain pine before bouncing off on a run.

The more urban they become, the more the Pongs are utterly convinced that they are 'bringing the countryside into their home'. To them even a mundane British lavatory pan is lake, forest and fountain all

in one. In season, the cistern rushes and gurgles bloo like an Alpine stream in flood. At other times when he stares at the jade-matic green, Mr Pong is like Narcissus by a woodland pool. For a luxury touch Mrs Pong pops a Spring Flowers sachet inside the Andrex Maze Roll Fresh'). Stacked about with heritage soap ('Eli- zabethan washing-balls'), sometimes she feels suddenly tropical instead and runs a lovely bath of wild orchid 'n' coconut foaming mousse.

Downstairs, Mrs Pong's daily may not use a vast amount of water, but she keeps oceans of industrialised scent on the move. She dusts with bursts of 'Springtime' Pledge, puts an Airwick 'Breeze' into the hoover (The room freshner you simply pop in your dustbag') and clips a flat plastic 'lemon' into the dishwasher. Should any- one secretly look into the dishwasher, it 'will not give offence'.

When it comes to evoking domestic mood, an industrial chemist is now the Proust of the aerosol can. Mrs Pong loves the new 'Moods' range of 'room frag- rances' which spray things the way they used to be. One can is 'reminiscent of an autumn evening' . . . sss . . . another is 'reminiscent of a spring morning' . . . sss . . . the third is reminiscent of a summer day. In contrast, the roses in the Pongs' trim garden smell of almost nothing at all.

In household products and personal scents the international 'fragrance indus- try' has rapidly expanded since 1982. In the UK alone, retail sales of scents for men and women were over £0.5 billion in 1987, with a pronounced shift towards 'fine fragrances.' Setting aside a handful of mid-20th-century French classics, 'fine' in this context means pricey Americanised synthetics backed by enormous advertising budgets.

According to a report on the UK scent market published by MSI (Marketing Strategy for Industry) last November, women are increasingly wearing these powerful synthetics all day, instead of just in the evening. British men also seem less hostile to scented things than at any time perhaps since 1900 (era of Eau de Portugal to lay the hair and of violet-scented shaving soap).. On top of all this, Pong mail will soon be on the way. The Western scent market is now so flooded that distribution is becoming difficult. The 'scent strips' which make glossy magazines so pungent will be soon also used in direct mail. Instead of hovering between hundreds of sparkling tester bottles in a shop, the potential customer will receive a scent sample at home. 'Direct mail virtually ensures the fragrance is sampled.'

Traditionally, scent-making evokes the romance of flower farms near Grasse, the Bulgarian rose harvest and less attractive- ly, the torture of battery-farmed civet cats in India. (A gland between genitals and anus is scraped out for the pungent subst- ance it contains.) But the following ques- tion from a trainee perfumer's current examination paper gives some idea of the modern 'flowers from the retort' produced by advanced organic chemistry. (I have supplied the answers): Give a one-word odour description appropriate to each of the following aroma chemicals: a) Citral [lemon]

b) Phenylethyl alcohol [rose] c) Galaxolide [musk] d) Alpha-ionone [violet] e) Linalyl acetate [herbaceous] 1) Eugenol [clove] g) Terpineol [lilac] h) Vanillin [vanilla] i) Amylcinnamic aldehyde [jasmine 1] j) Benzyl acetate [jasmine 2]

In various combinations determined by a man always called Le Nez, these subst- ances increasingly produce scents known as `straight-ups'. These do not chemically alter on the skin of the wearer to give the subtle individuality once prized in French classics. Instead, Mrs Pong's blast of Straight Up smells exactly the same on everyone else and relentlessly goes on and on all day.

To find successful scents of a previous age I recently arrived at Cavendish Square to learn a bit about the man who invented scent 'marketing' in London. This was Eugene Rimmel, friend of Victor Hugo and founder of the French Hospital in Soho (1867). In a light first-floor room swagged with bronze and dull-gold fabric over gilt rams' heads (Cosmeticians' Napoleonic), I spent a morning being quietly seduced by the mid-19th century marketing techniques of Rimmel, 'the Cal- vin Klein of his day'.

In a huge collapsing cardboard box (which smelt of archives and nothing else) were hundreds of prettily printed labels, ads and flowery almanacs. On labels bear- ing royal crests across Europe from Lon- don to Russia, was a great array of one-flower scents and simple 'bouquets'. The late 19th-century love of violets fi- gured often even in Rimmel's discreet face powder (`poudre de riz aux violettes de Nice') along with roses, sweet-peas, elder-

flowers, white heliotrope and Mitcham lavender. Because romance must always lie elsewhere, place-names figured in Rim- mel's imaginative sales methods. If, for example, I were passing the hours in a stuffy London drawing-room, the Isle of Wight Bouquet might have suggested sim- ple summer freedom (and Osborne). On a light green label printed with hills and a glimpse of sea came a few lines of Shakespearian cachou verse:

Like the sweet south Breathing o'er a bank of violets, Stealing and giving odour.

I also wondered about the New Zealand Bouquet, the Florida Water bottle deco- rated with rather English-looking red Indi- ans (perhaps inspired by woodcuts of Pocohontas), the famous Jockey Club Bouquet (with a sporty label showing horses being ridden at full stretch), Cro- quet Club and something just called Ess- ence of Kayu Whangee. When an hour or so later I opened a glass display cabinet full of bottles with big facetted stoppers, there was nothing left but the indistinct scent of long-decayed sweetness.

The curator of Britain's first compre- hensive Museum of Perfumery (surprising- ly, a very successful ex-Aberdeen oil-man called Barry Gibson) believes that the Western scent trade is now 'a very tired industry'. When this 'V&A of the nose' opens in Union Street, Aberdeen next spring, it will contain for sale delicate reconstructions of 19th century single- flower and bouquet scents to cater for a British nose now jaded with overwhelming modern synthetics. He believes a return to classic simplicity is the future direction of the scent-maker's craft. Exhibits for the museum are now sought from the public.

In 18,000 square feet of space, Mr Gibson and his partner James Michie of Ingersetter's, Royal Deeside, are recon- structing the Laboratory of Flowers (Piesse & Lubin's huge mid-19th-century scent manufactory in St Katherine's Dock, Lon- don) and, on a more rural scale, Ephraim Potter's lavender drying sheds and steam distillation plant at the height of its produc- tion near Mitcham in 1851. Before `shab' (a fungal disease of lavender) helped to destroy English lavender farming in the 1880s, over 800 acres of Surrey were devoted to flower and herb growing for the London scent and pharmacy trade. (The arms of the former Borough of Mitcham continued to carry two sprigs of lavender on a gold blackcloth.)

Recently, I dashed down to Mitcham with Robert Allison, heir apparent of D. R. Harris of St James's Street, the Club- land chemist established in 1790. Leaving Burberry'd visitors to look at mahogany cases full of oig natural sponges, bone- handled toothbrushes and simple English glass bottles full of bright pink mouthwash,

we went to see Harris's little factory with climbing geraniums growing out of old sinks by the door. The little factory is close to Mitcham Parish Church. Beneath window-sills filled with more geranium pots, two or three people patiently worked in a pleasingly creative muddle of wooden retort stands, big filter papers and an electric stove on which to 'cook' some of the preparations. It seemed to be a busi- ness perfectly poised between the old- fashioned apothecary and modern indust- rial chemistry. Whirling back past Same- Day Snaps, the blue plastic fascia of the Video Library and a brand new McDo- nald's, I explained that this is the Provence of England. Harris's factory is in Mitcham because 'as an .English scent firm you took root in the land'.

In August 1914 a reporter from the Daily Mail walked from here to Carshalton to discover what was left of England's flower harvest. 'In every direction,' he wrote, 'the low hillsides of the farm are swept with bloomy pastel tints of reapers in the fields. As the day wears on, the fragrance rises like incense in the air, wandering tribes of paper-white butterflies drift over the fields and in the clear depths of blue sky, larks descant the joy of life.' The English still prefer to smell vaguely of hay and even in a traffic-jammed suburb, there are hints, if we seek them, of the fields beneath.

Previous page

Previous page