History on the March

THERE still seems no cessation of the paperback flood and, indeed, many reprints have appeared which many people would not expect to have a large sale. Yet manifestly this is not so, for publishers, as they so frequently tell us, are not solely in business for altruistic reasons. It seems obvious, therefore, that in the expanding paper- back market the interests of the producer, dis- tributor and consumer of books coincide in an extraordinary way.

Of recently issued historical paperbacks, there's little doubt that the first three volumes of Arnold Toynbee's A Study of History (O.U.P. for the R.I.I.A., 15s. each) are the best value. The edition is unabridged and the pagination is the same as in the hardback version, so all references apply. These first volumes include Toynbec's introduction and his description of the genesis and growth of civilisations. The work is, of course, enormously impressive with its enormous mass of erudition, especially when dealing with non-Western civilisations. But the frame of reference is depressingly deterministic, an assertion of belief rather than a carefully con- structed philosophy of history.

One of the best essays on Toynbee ever written appears in another famous but much briefer book on the meaning of history, R. G. Collingwood's The Idea of Histoiy (O.U.P., 75. 6d.). 'He regards the life of a society as a natural and not a mental life, something at bottom merely biological . . . a scheme of pigeon-holes elaborately arranged, and labelled, into which ready-made historical facts can be

Collingwood's work ranges from the Greeks to our own age in its dissection of historiography, and is an extremely rewarding book. Although perhaps he exaggerated in seeing human history as the history of thought, surely he was right in insisting that we understand the past through Imaginative re-creation and not, as the social scientists say, by collecting and classifying data.

Here one should mention The Poverty of Historicism, by Karl R. Popper (Routledge, Kegan Paul, 6s.), one of the most effective attacks on the various theories of determinism ever written. Popper's explosion of 'the laws of history' or 'the laws of progress' has a tremen- dous relevance to the historicist fallacies, or rather the applied doctrines of historical in- evitability which eche through our society. A good illustration of these concepts in political thought lies in Isaac Deutscher's Stalin (O.U.P., 10s. 6d.). Though particularly good on Stalin's accession to power and his relationships with Churchill and Roosevelt, this book's underlying thesis is disturbing. It is that collectivisation and forced labour were justified because the USSR had to be industrialised. The great purges were necessary to Stalin because otherwise Russia might have succumbed to Nazi Germany. The false, terrible implication is that only in these Ways could the USSR fulfil the destiny of the Revolution and become a super-power. Deuischer justifies Stalin because he assumes he Was an agent of history. One might as well say, as no doubt Marxists do, that Caligula was ob-

jectively preferable as the embodiment of the principate to the chaos of the Roman Republic.

Three other classic studies on the history of Communism are being distributed by the Cresset Press for the University of Michigan. Nicholas Berdyaev's The Russian Revolution (12s. 6d.), first published in 1931, 'discusses how the Chris- tianity of Holy Russia became the cult of Lenin, how the emotions which crystallised around the concept of original sin were transferred to the imperialists and capitalists. Two essays by Rosa Luxemburg, The Russian Revolution and Leninism or Marxism (10s. 6d.), are polemical attacks on democratic centralism, while perhaps the most brilliant of these three studies is Trotsky's Terrorism and Communism (12s. 6d.). This demolition of Lenin's best-known Socialist adversary, Karl Kautsky, is historically interest- ing as foreshadowing the suppression of the Kronstadt uprising, for Kautsky was denounced as belonging to 'the camp of the counter- revolution.' And not only Kronstadt, of course, but Trotsky's own liquidation by the logic of the apparatus he himself had helped to build.

A rather different school of history is repre- sented by Sir Winston Churchill, the last of the great Whig historians. First published in 1899, The River War (Four Square, 3s. 6d.), the story of the reconquest of the Sudan, ends with this magnificent invocation of the imperial idea:

Here, then, is a plain and honest reason for the River War. To unite territories that could not indefinitely have continued divided; to com- bine peoples whose future welfare is inseparably intermingled; to collect energies which, con- centrated, may promote a common interest; to join together what could not improve apart —these are the objects which, history 'will pro- nounce, have justified the enterprise.

Also now in print are two volumes of Sir Winston's History of the English-speaking Peoples, The Birth of Britain and The New World (Cassell, 10s. 6d. each), which take the story from the ooze to the eviction of James II. In this 'personal view of the processes whereby English-speaking peoples throughout the world have achieved their distinctive position and character,' the writer castigates the bad and eulogises the good. Statecraft, the minutia; of politics, dynastic intrigue are all related to great national ends, and, of course, there is a unique insight into the part played by war in our history. The machinations of the Church are dismissed with an almost Gibbonian distaste for religion, a barbarism almost as reprehensible as that of economics. There is no manifestation of his- toricism here, no power worship; this is both literature and history, a work which will live for many years with all kinds of people.

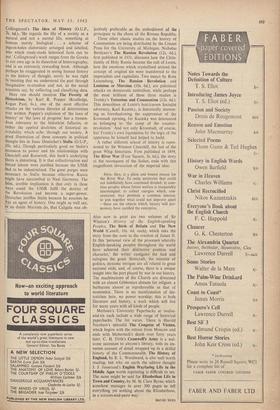

Methuen's University Paperbacks at twelve- and-six each include a wide range of historical paperbacks. The list varies. There is Harold Nicolson's splendid The Congress of Vienna, which begins with the retreat from Moscow and ends with Metternich's death over forty years later. C. H. Firth's Cromwell's Army is a wel- come accession to anyone's library, with its im- mense amount of detail wrapped up in a skilful history of the Commonwealth. The History of England, by E. L. Woodward, is also well worth reading, but why on earth the editors thought J. J. Jusserand's English Wayfaring Life In the Middle Ages worth reprinting is difficult to see. The same might be said for Elizabethan Life in Town and Country, by M. St. Clare Byrne, which somehow manages in over 300 pages to tell everything yet nothing about the Elizabethans, in a scissors-and-paste way.

DAVID 'REES

Previous page

Previous page