Yorkshire Accent •

THE most adventurous of the new paperback series is Penguin's eight contemporary yogi novelists. Among those already published, Daina Storey's This Sporting Life (3s. 6d.) is outstand- ing. It gives me more hope for the novel in this country than any other I have read. Arthur Machin, the central character, is a professional Rugby League player in a Northern town. He has a full awareness of the society in which he lives, and such rebellion as he harbours Is channelled into the Saturday afternoon game. The only person who can touch him is his land- lady, a not-so-young widow with two bawling kids. She accepts his fame and his money be- grudgingly, frightened of giving herself to a man she has no confidence of keeping, and despising him because he has broken outside the only life she has ever known: cramped, squalid, 'respectable' and safe. Arthur, intelligent enough to see this, is unable to leave her, for he sees at the same time that she and her two pathetic kids need him' and his money as nobody else does. She is real to him as nobody else is.

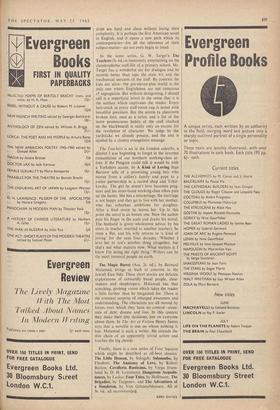

The outside is as much a game of Rugby ag his career, and he plays it the same way : cannily, and like a tiger. When she dies he has nothing left except the prospect of ten more years as ft dwindling player, his body battered into middle age. 'I had my .ankles strapped, got dressed and put my teeth in.' That is the last sentence, and a fair sample of the prose. It is tough, dicing the action neatly and finely. There is nothing injected into the novel from outside. It is all gerierated by the action itself, and the relation- ships are hard and clean without losing, their complexity. It is perhaps the first American novel in English, and it opens a new path which its contemporaries—for all the relevance of their subject-matter--do not even begin to tread.

In the same series, G. W. Target's The Teachers (3s. 6d.) is immensely entertaining on the claustrophobic staff-life of a primary school. Mr. Target has a wonderful ear for dialogue and he records better than tape the stale wit and the mechanical sarcasm of the staff. By contrast the kids are alive—the pre-eleven-plus world is the only one where Englishmen are not conscious et segregation. But without denigrating, I should call it a superficial novel in the sense that it is the surface which captivates the reader. Every hair-crack in every staff-room cup is noted with beautiful precision. But the action (a classroom broken into, used as a toilet, and a list of the more promiscuous habits of the staff chalked on the blackboard) is really only an excuse for the revelation of character. We judge by the yardsticks we already possess,. and the end is spoiled by a clumsy evangelistic message.

The Teachers is set in the London suburbs, a district 1 was beginning to forget in the inverted romanticism of our northern working-class ar- tists. If the Penguin could talk it would be with a Yorkshire accent. In A Kind of Loving Stan Barstow tells of a promising young boy who moves from a collier's family and pops to a junior partnership in a record shop and Tchai- kovsky. The girl he doesn't love becomes preg- nant and his strait-laced working-class ethos puts up the banns. She has a miscarriage, the marriage is not happy and they go to live with her mother, who has suburban ambitions for daughter. After a final storm he leaves her. Up to this point the novel is an honest one. Now the author puts his finger in the scale and draws his moral. The husband is given wholesome advice by his sister (a teacher married to another teacher); he rents a flat, and his wife returns to 'a kind of loving' for the next four decades, .'Whether I love her or not's another thing altogether, but that's not what matters now. What matters is I know I'm doing the right thing.' Writers can be the most immoral people on earth.

The Magic Barrel (Ace, 2s. 6d.), by Bernard Malamud, brings us back to concrete in the Jewish East Side. These short stories are delicate explorations of outwardly banal people, shoe- makers and shopkeepers. Malamud has that searching, probing vision which takes the reader a little farther than he bargained for. There is the constant surprise of enlarged awareness and understanding. The characters are all moved by forces over which they have no control--exter- nals of debt, disease and loss. In this context they make their tiny decisions, lost on everyone about them. In The Art of Fiction Henry James says that a novelist is one on whom nothing is lost. Malamud is such a writer. He extends the thin chain of an apparently trivial action and touches the big chords.

Finally, there is a new series of Four Squares which might be described as off-beat classics: The Little Demon, by Sologub; Salammbo, by Flaubert; The Anatomy of Love, by Robert Burton; Cavalleria Rusticana, by Verga (trans- lated by D. H. Lawrence); Dangerous Acquain- tances, by Laclos; Four Tales, by Hoffmann; The Brigadier, by Turgenev; and The Adventures of a Simpleton, by Von Grimmelshausen. All at 3s. 6d., all recommended.

JOHN DANIEL

Previous page

Previous page