Books

The state of the fiction

Paul Ableman

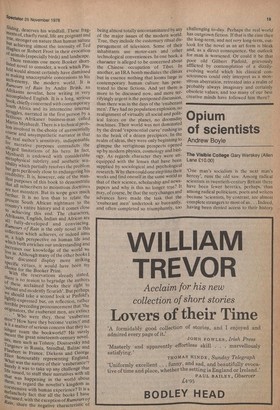

The Sea, The Sea Iris Murdoch (Chatto & Windus £5.50): Winner of the 1978 Booker Prize for Fiction The short-list for-the Prize also included: Jake's Thing Kingsley Amis (Hutchinson £4.95) The Bookshop Penelope Fitzgerald (Duckworth £3.95) God on the Rocks Jane Gardam (Hamish Hamilton £4.95) A Five-Year Sentence Bernice Rubens (VV.H. Allen £4.25) Rumours of Rain Andre Brink (W.H. Allen £5.95) The Winner of the 1978 John Llewelyn Rhys Memorial Prize was: The Sweets of Pimlico A. N. Wilson (Secker & Warburg £3.50): The Winner of the 1978 David Higham Prize was: Sliding Leslie Norris (Dent £3.95) 'It may happen in the next hundred years that the English novelists of the present day will come to be valued as we now value the artists and craftsmen of the late eighteenth century. The originators, the exuberant men, are extinct and in their place subsists and modestly flourishes a generation notable for elegance and variety of contrivance.'

Many readers will recognize the above words as the start of Evelyn Waugh's confessedly autobiographical novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pin fold. They identify, in the two virtues specified, 'elegance and variety of contrivance', what are perhaps the closest that can be found to positive criteria for assessing these very heterogeneous books. Happily the reader will find a good deal of both qualities in their pages although nothing like the abundance contained in the works of the Old Reactionary himself.

With her nineteenth novel, Iris Murdoch has won the £10,000 jackpot of the Booker Prize and there will be jubilation in the land. Although never one of her most fervent adreirers, I was beginning to share the rejoicing as I turned the pages of The Sea, The Sea but alas found enthusiasm waning by the end of the first section, which contains less than a fifth of the work's five-hundred pages. The accomplished opening passage, entitled 'Prehistory', introduces us to a wizard of the theatre who, disenchanted with the tinsel, has retired to a spare house on a rocky coast to reflect on his days and purge himself of meretricious values. The interweaving of three themes is expertly handled in crisp prose. Charles Arrowby; the ex-showman, experiments with autobiography, describes his initial adventures with solitude, the sea and his own con sciousness and begins to fill in his background. Rhythmically punctuated with accounts of his eccentric meals, this section achieves a classical elegance and promises well. But there is a worm, or rather a sea-monster, in the bud. Arrowby spies a coiling head above the waves and with a sinking heart the reader finds Miss Murdoch's old nemesis, mythological metaphysics, beginning to dog both her and her hero. By the start of the second section, called 'History', new elements of what soon becomes recognisable as the Perseus myth have begun to surface, the tough, stately prose to sag and the narrative to collapse in disarray. Significantly, Arrowby, as he pursues his now-aged childhood sweetheart, Hartly, whom he has incredibly chanced upon residing in the village, never again shares with the reader one of his quaint, original feasts. Something went wrong with this book and I hazard the guess that after Miss Murdoch, impressionistically but compellingly sketching her protagonist's past, had reminisced lyrically about his first love for Hartley, she became infatuated with her creation and allowed the tiresome old woman to appropriate the book. What is demonstrable is that, as bi7arre events and characters are heaped up, a growing air of improvisation distorts the structure and, although still offering touching moments, a number of epigrams and some telling evocations and observations, the work never recovers its balance.

The other heavyweight among the, six authors on the Booker short-list was Kingsley Amis, and Jake's Thing is a thoroughly professional, often amusing, consistently well-written book. It scores quite high as regards 'elegance' but goes over the top with 'variety of contrivance'. The outré therapies to which Jake resorts in the attempt to cure his qualified impotence are less contrivance than inflated detail. This is not so much a novel as a hypertrophied portion of a novel. Compelled to view the events and characters, in themselves substantial, from the level of the groin impedes the author from attaining the scope which even a humorous novel should have. Many people, especially women, seem to have detected the accents of male chauvinism in this work. It struck me as much more an elegy for the things intellectual, emotional, social and cultural as well as purely sexual that time devours.

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald is an engaging but slight account of a woman's abortive attempt to run a bookshop in a small Suffolk town. The establishment prospers briefly but local interest is against her and finally she rides out of town 'with ed shame'. onpe '. nRictiin The Bookshop sense in which the word applies to, saY1 Blake and Turner, an amateur book, seer°. ingly more concerned to order and express experience than to please readers and, f°If that reason, may well please a stratum 0 readers more than Jane Gardam's very pro' fessional God on the Rocks. The latter' a superior romance about a young girl a,. seaside town, observing adult behavioui and, inescapably, acquiring knowledge, °°, all of it welcome. The plot is a complieateu, anatomy of the connections, sometime' savage, linking a group of very varied PO,. ple. The catalyst is supplied by the chilu? nursemaid, a voluptuous, kind-hearted troli lop. The book is graced by a wry thread °t humour and is tuned to the Old Testame° language of her fundamentalist, but lecher:, ous, father. It is a 'romance' in the technicwf sense that it accepts certain conventions narrative and reader-sensibility but is, all that, a fresh, honest and charming b°°'''f Almost the reverse is lamentably true Bernice Ruben's A Five-Year Sentence, tiles only work in this collection which imPlign the judges' discrimination. This ill-writtea 'black whimsy' concerns a lady originallYt from an orphanage -who, upon retiremen, after a lifetime of dismal work in a vice° factory, is deterred from her intention t°2 commit suicide by the farewell gift ef five-year diary, which she regards as a olYcis: tic incitement to stay alive for that peri°, She cheers up, paints the image of a 111' onto a mirror for company, is deceived bYae male prostitute and finally strangles th, matron of her old orphanage. The violenc.` and coy eroticism scattered throughout Its pages provide no antidote to the stic" sentimentality from which this work is VIM Gilbert Pinfdld would doubtless bale resisted, with goggling incredulity, al32; attempt to install him as chairman of Booker Panel. Had he been prevailed tIP°' to serve, I suspect he would have striven t° award the prize to a book that was not eve° considered for it, A. N. Wilson's The Sweets of Pimlico, a delightful account of a gir.r,,s growing infatuation for a very old, very ric' and outrageous German baron. Had I a panellist, I would have been strange tempted to support his choice. Wilson's ls an enchanting first novel, rich in-the plaits' ible, and yet original and idiosyncratic. arabesque of plot that I take Pinfold-W', to have meant by 'variety of contrivance, and written, although with occasional cavalier contempt for accepted syntax, in 8 style that has intrinsic elegance, as well as great charm and wit. Still, Mr Wilson ea° take comfort from having joined the tolerably distinguished list of winners of the john Llewelyn Rhys Prize, first awarded in 1944' It is granted for the best novel by an autb04 under thirty the £100 will doubtless provide Mr Wilson with that precious sense of seeurity which helps an artist to give of his best.

• Leslie Norris, pocketing the £500 of the David Higham prize for the best first work of fiction for his collection of short stories Sliding, deserves his windfall. These fragments of, chiefly rural, life are poignant and stronger on nature than human nature but achieving almost the intensity of Ted Hughes or Robert Frost in their evocation of animals (especially birds) and landscape. There remains one more Booker shortlisted novel to consider, a work which Pinfold would almost certainly have dismissed as making unacceptable concessions to his arch-enemy, the modern world, It is Rumours of Rain by Andre Brink, an Afrikaans novelist, here writing in very book, English. It is a long, serious „ueok, chiefly concerned with contemporary South Africa and its internecine internal s,.49ggles, narrated in the first person by a fictitious Afrikaner business-man called Martin Mynhardt. There is a technical problem involved in the choice of an essentially coarse and unsympathetic narrator in that for real author's sensitivity. indispensable 'or narrative purposes contradicts the alleged limitations of his hero. In fact, MYnhardt is endowed with considerable Metaphysical subtlety and aesthetic senSibility partially resolves the problem but gets perilously close to endangering his Freda:614y. It is, however, one of the manifest Purposes of this book to demonstrate that all subscribers to monstrous doctrines are not monsters. But its scope goes much further. It is no less than to relate the present South African nightmare to the country's entire history and it comes close to achieving this end. The characters, Afrikaans, English, Indian and African. are all fully-developed and convincing. Rumours of Rain is the only novel in this collection which achieves, or indeed aims at, .a high perspective on human life and which both enriches our understanding and ,Increases our knowledge of the world we live in. Although many of the other books I have discussed display more striking Specific virtues, it would have been my Choice for the Booker Prize. With the reservations already stated. there is no reason to begrudge the authors ?f these acclaimed books their right to subsist and modestly flourish'. But perhaps 1Ye should take a second look at Pinfold's ightlY-expressed but, on reflection, rather terrible preceding pronouncement thatthe originators, the exuberant men, are extinct • • Who were they, these 'exuberant ill. en'? How have they become 'extinct and ,Is it a matter of serious concern that they no '1:Inger roam the bookworld? He surely Meant the great nineteenth-century novelists, men such as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and _furgenev in Russia, Stendhal, Balzac and Fja.ubert in France, Dickens and George VrIot honourably representing England Surely was the nature of their 'exuberanc,e ? life it was to take up any challenge that life Issued, to stuff their narratives with all that was happening in the world about them, to regard the novelist's kingdom as coextensive with human experience? It is a M..elancholy fact that all the books I have thscussed, with the exception of Rumours of share the negative characteristic of being almost totally uncontaminated by any of the major issues of the modern world. True, they include the customary ritual disparagement of television. Some of their inhabitants use motor-cars and other technological conveniences. In one book, a character is alleged to be concerned about the Chinese occupation of Tibet. In another, an IRA bomb mediates the climax but in essence nothing that looms large in contemporary human culture has penetrated to these fictions. And yet there is more to be discussed now, and more terrifyingly urgent is the postponed discussion, than there was in the days of the 'exuberant men'. They had no population explosion, no realignment of virtually all social and political foi-ces on the planet, no doomsday machines. Their world was not dominated by the dread 'exponential curve' rushing us to the brink of a dozen precipices. In the realm of ideas, they were only beginning to glimpse the vertiginous prospects opened up by modern physics, cosmology and biology. As regards character they were unequipped with the lenses that have been supplied by sociological and psychological research. Why then could one step into their works and find oneself in the same world as that of their science, scholarship and newspapers and why is this no longer true? It may, of course, be that the very changes and advances have made the task that the 'exuberant men' undertook so buoyantly, and often completed so triumphantly, too challenging to-day. Perhaps the real world has outgrown fiction. If that is the case then the long-term, and not very long-term, outlook for the novel as an art form is bleak and, as a direct consequence, the outlook for man is worsened. Or could it be that poor old Gilbert Pinfold, grievously afflicted by contemplation of a dizzilyevolving world which his classical consciousness could only interpret as a monstrous aberration, retreated into a realm of probably always imaginary and certainly obsolete values, and too many of our best creative minds have followed him there?

Previous page

Previous page