Cinema

New York Stories ('15', selected cinemas)

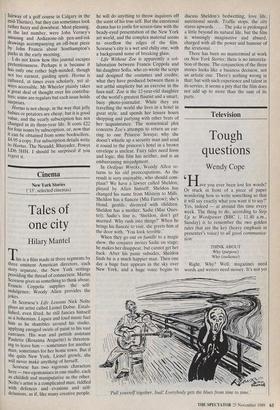

Tales of one city

Hilary Mantel

This is a film made in three segments by three eminent American directors, each story separate, the New York settings providing the thread of connection. Martin Scorsese gives us something to think about; Francis Coppola supplies the self- indulgence; Woody Allen provides the jokes.

In Scorsese's Life Lessons Nick Nolte plays an artist called Lionel Dobie. Estab- lished, even feted, he still fancies himself as a bohemian. Liquor and loud music fuel him as he shambles around his studio, applying enraged swirls of paint to his vast canvases. His wan and pettish assistant Paulette (Rosanna Arquette) is threaten- ing to leave him — sometimes for another man, sometimes for her home town. But if she quits New York, Lionel growls, she will never make anything of herself.

Scorsese has two vigorous characters here — two egomaniacs in one studio, each as childish and manipulative as the other. Nolte's artist is a complicated man, riddled with defences and evasions and self delusions, as if, like many creative people, he will do anything to throw inquirers off the scent of his true self. But the emotional drama has to jostle for screen-time with the beady-eyed presentation of the New York art world, and the complex material seems to overflow the edges of the film. Scorsese's city is a wet and chilly one, with a background noise of breaking glass.

Life Without Zoe is apparently a col- laboration between Francis Coppola and his daughter Sofia, who co-wrote the script and designed the costumes and credits; what they have produced between them is not artful simplicity but an exercise in the faux-naIf. Zoe is the 12-year-old daughter of the world's greatest flautist and a smart, busy photo-journalist. While they are travelling the world she lives in a hotel in great style, and spends her leisure hours shopping and partying with other brats of her acquaintance. The nonsensical plot concerns Zoe's attempts to return an ear- ring to one Princess Soraya; why she doesn't whistle up a security man and send it round to the princess's hotel in a brown envelope is unclear. Fairy tales need form and logic; this film has neither, and is an embarrassing misjudgment.

In Oedipus Wrecks, Woody Allen re- turns to his old preoccupations. As the result is very enjoyable, who should com- plain? We have a lawyer called Sheldon, played by Allen himself; Sheldon has changed his name from Milstein to Mills. Sheldon has a fiancée (Mia Farrow); she's blond, gentile, divorced with children. Sheldon has a mother, Sadie (Mae Ques- tel); Sadie's line is, 'Sheldon, don't get married. Why rush into things?' When he brings his fiancée to visit, she greets him at the door with, 'You look terrible.'

When they go out en famille to a magic show, the conjurer invites Sadie on stage; he makes her disappear, but cannot get her back. After his panic subsides, Sheldon finds he is a much happier man. Then one day a huge face appears in the sky over New .York, and a huge voice begins to

discuss Sheldon's bedwetting, love life, nutritional needs. Traffic stops, the city stares upwards. . . . The joke is prolonged a little beyond its natural life, but the film is winningly imaginative and absurd, charged with all the power and humour of the irrational..

There has been no mastermind at work on New York Stories; there is no interrela- tion of theme. The conjunction of the three stories looks like a business decision, not an artistic one. There's nothing wrong in that; but with such experience and talent in its service, it seems a pity that the film does not add up to more than the sum of its parts.

Previous page

Previous page