The treason of the Vice-Chancellors

STUDENTS IAN Ma cGREGOR

This is the second of three articles by a senior university teacher.

It is said in America at the moment that the outcome of the presidential election depends on the un-young, the un-black and the un-poor. In Britain the fate of our universities has fallen into the hands of the Vice-Chancellors and the students. The great majority of university teachers, who are un-young, un-radical and un- enamoured of most student demands, are almost without influence. And it is on them, not on administrators and undergraduates, that the future of .Britain's universities depends. More and more of them are getting fed up.

Suggestions of an unholy alliance between Vice-Chancellors and militant students may sound implausible on the face of it. Yet the existence of such an alliance—tacit to be sure —is believed in by increasing numbers of sub- senatorial academics across the country.

The dynamics of student politics are simple. A demand arises for change, usually amongst a minuscule minority. The student leaders either sympathise with it or they do not. If they do, they press it eagerly on the university authori- ties. If they do not, they press it all the same, since most elected student leaders are terrified of being outflanked by extremists and of ap- pearing pro-establishment. Faced with a choice of combating the authorities or seeming to oppose the claims of fellow students, even the most moderate student leader usually opts for combat. After all, he is committed to success as a student politician; he is not committed to the quality of his university, especially since (in the great majority of cases) he will be leaving it for ever in a few months' time.

Meantime two seemingly contradictory de- velopments take place amongst the student mass. The great majority of students, anxious to lead normal lives and finding the strident tone of student politics increasingly distasteful, lapse into apathy; they play no part in student affairs. But at the same time this same apathetic majority becomes steadily more convinced of the legitimacy of the militants' demands. This Is natural since the militants invariably talk the unexceptionable language of democracy, students' rights and participation, and since there are alway minor grievances that can be made to seem major or, worse, fitted into a pattern of alleged authoritarianism. Essex as usual provides tffe most extreme instance of a general phenomenon; the uprising there last spring—when the majority of students believed a concrete injustice had been done—climaxed two years of widespread undergraduate alienation from undergraduate politics.

The dynamics of top-level university politics are more subtle. The Vice-Chancellors find themselves under increasing pressure from the National Union of Students. The NUS leaders in .turn are under pressure from the militants, by whom they are determined not to be outbid. But who is exerting comparable pressure on the Vice-Chancellors? The answer is, effectively, nobody. The Government is not certain what it wants, except that the present storm shall pass; for the best of reasons k is reluctant to get involved in university affairs. The Associa- tion of University Teachers has no clear view. Businessmen in Britain who donate to univer- sity funds, feel—unlike their American counter- parts—inhibited about stepping in.

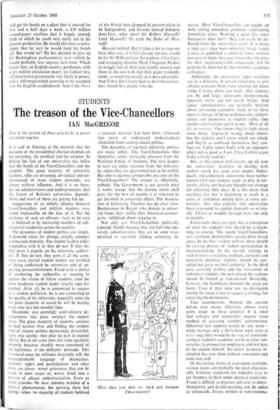

Not only are Vice-Chancellors politically exposed. Simply because they are full-time uni- versity administrators, they are in some ways unsuited to represent abiding university in- 'How dare you turn me back just because I'm a student!' terests. Most Vice-Chancellors are caught up with solving immediate problems, confronting immediate crises. Wanting a quiet life—what bureaucrat does not?—they can easily be de- flected from the university's goals. It is many a long year since most university heads taught a class or published a scholarly tome; without pressure on them, they may forget that the price for their negotiating-table concessions will be paid not by them but by their humbler academic colleagues.

Admittedly, the universities' upper echelons are in a difficulty. A certain reluctance to give offence restrains them from uttering the home truths I wrote about last week—that students are, by and large, adolescent, inexperienced, ignorant, naïve and not overly bright. And senior administrators are naturally hesitant about advancing arguments likely to lay them open to charges of being undemocratic, authori- tarian and insensitive to student rights. One teacher-administrator put it to me: Most of all it's so wearing. One knows they're right about some things hopelessly wrong about others; but the students don't know which are which, and they're so confused themselves they con- fuse me. I play tennis badly with an opponent who's not as good as I am; I fear I often argue badly with the students.'

But, as this remark half-reveals, up till now the universities' weakness in dealing with student revolt has gone even deeper. Indivi- dually and collectively, universities have neither known what role students ought to play in uni- versity affairs, nor had any thought-out strategy for enforcing their ideas. It is this more than anything else that is beginning to result in a crisis of confidence among dons at some uni- versities. This also explains why universities have responded to student demands so erratic- ally. Efforts to muddle through have led only to muddle.

Fortunately there are signs that a conception of what the students' role should be is begin- ning to emerge. The recent Vice-Chancellors- NUS statement distinguishes among three broad areas. In the first, student welfare, there should be varying degrees of student participation in decision-making. In the second, relating to such matters as teaching methods, curricula and long-term planning. students should be con- sulted but given no final authority. In the third area, covering staffing and the assessment of individual students, the part played by students should be limited or non-existent. Inevitably, however, the boundaries between the areas are fuzzy. Even if they were not. to distinguish among the areas is not to suggest a strategy for enforcing the distinctions.

Take examinations. (Indeed, the current debate over exams illustrates almost every point made in these articles.) It is clear that colleges and universities require some method of assessing students' performance. Otherwise few students would do any work— many manage only a thirty-hour week even as it is—and there would be no way of communi- cating a student's academic worth to other uni- versities, to prospective employers, and not least to the student himself. No major academic in- stitution has ever done without assessment and none ever will.

Of the various forms of assessment available, written exams are probably the least objection- able. Uniform standards are tolerably easy to set. Students sit them under identical conditions Fraud is difficult to practice and easy to detect Anonymity and double-marking can be added as safeguards. Essays written in non-examina- tion conditions may enable the student to dis- play research ability and to develop more com- plex arguments; but are much harder to mark fairly, and fraud (beta-plus essays at fifteen bob a time) is almost inevitable. So-called 'objective' tests used in America test memory and certain to-type skills but not much else. As for personal assessment by class teachers, this method is guaranteed to penalise equally the shy and the talkative, and to reward pretty girls with good figures.

All this is fairly humdrum; reasonable men can reasonably differ. As it happens, written forms of assessment, whether produced in exam conditions or not,-tend to produce very similar results. But to hear undergraduates at some universities—especially the new ones—debate exams is to ascend to cloud nine. `Exams,' they say, 'merely test one's memory for facts' (any student believing that should try relying on memory alone and see what happens). 'One can only answer exam questions superficially' (maybe, but if you read a few hundred scripts, some answers turn out to be just a bit more superficial than others). 'People get very tense during exams' (yes, and isn't it odd how the bright still have an uncanny way of doing better than the dim?). 'Mistakes are made; people get put in the wrong class' (yes, and trains are sometimes late, so should we abolish the rail- ways?). The marking of exams is ideologically biased' (yes, undoubtedly there is a strong bias in favour of intelligence and knowledge, against stupidity and ignorance). 'I remember once,' a Sussex don told me, 'reading a colleague's manuscript. There was one passage that was so incredible I didn't know whether to give up and say nothing. or scrawl "Balls" all over the page. I feel like that practically every time I hear students talking about exams.'

At -several universities drastic reform of examinations is now at the top of the radical agenda. The strategic principles that °fight td govern the universities' handling of this par- ticular demand are, in my view, applicable across the board. I shall be discussing what these principles should be in a final article next week.

Previous page

Previous page