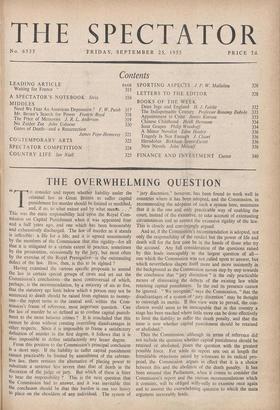

THE OVERWHELMING QUESTION

o consider and report whether liability under the criminal law in .Great Britain to suffer capital punishment for murder should be limited or modified, and, if so, to what extent and by what meaits. . . ." This was the main responsibility laid upon the Royal Com- mission on Capital Punishment when it was appointed four and a, half years ago, and one which has been honourably and exhaustively discharged. The law of murder as it stands is inflexible: a life for a life; and it is agreed unanimously by the members of the Commission that this rigidity—for all that it is mitigated to a certain extent in practice, sometimes by the prosecution, occasionally by the jury, but most often by the exercise of the Royal Prerogative—is the outstanding defect of the law. How, then, is this to be righted ?

Having examined the various specific proposals to amend the law in certain special groups of cases and set out the Commission's conclusions—the most controversial of which, perhaps, is the recommendation, by a majority of six to five, that the statutory age limit below which a person may not be sentenced to death should be raised from eighteen to twenty- one—the report turns to the central and, within the Com- mission's frame of reference, most important question. Can the law of murder be so defined as to confine capital punish- ment to the more heinous crimes ? It is concluded that this cannot be done without creating overriding disadvantages in other respects. Since it is impossible to frame a satisfactory definition of murder in the first degree, it follows that it is also impossible to define satisfactorily any lesser degree.

From this position to the Commission's principal conclusion is a short step. If the liability to suffer capital punishment cannot practicably be limited by amendment of the substan- tive law, there remains the alternative of placing power to substitute a sentence less severe than that of death in the discretion of the judge or jury. But which of these is fitter to bear the responsibility ? This is the next question that the Commission had to answer, and it was inevitable that the conclusion should be that this burden is one too heavy to place on the shoulders of any individual. The system of " jury discretion," however, has been found to work well in countries where it has been adopted, and the Commission, in recommending the adoption of such a system here, maintains that it is the one and only practicable way of enabling the court, instead of the executive, to take account of extenuating circumstances and so correct the excessive rigidity of the law. This is closely and convincingly argued.

And so, if the Commission's recommendation is adopted, not only the responsibility of the verdict but the power of life and death will for the first time be in 'the hands of those who try the accused. Any full consideration of the questions raised by this leads inescapably to the largest question of all— one which the Commission was not called upon to answer, but which nevertheless shapes itself more and more insistently in the background as the Commission moves step by step towards the conclusion that " jury discretion " is the only practicable means of eliminating the defects of the existing law while retaining capital punishment. In the end its presence cannot be ignored. " We recognise," says the Commission, " that the disadvantages of a system of ' jury discretion' may be thought to outweigh its merits. If this view were to prevail, the con- clusion would seem to be inescapable that in this country a stage has been reached where little more can be done effectively to limit the liability to suffer the death penalty, and that the issue is now whether capital punishment should be retained or abolished."

Thus the Commission, although its terms of reference did not include the question whether capital punishment should be retained or abolished, poses the question with the greatest possible force. For while its report sets out at length the formidable objections raised by witnesses to its radical pro- posal, the Commission argues in effect that it is a choice between this and the abolition of the death penalty. It has been ensured that Parliament, when it comes to consider the Commission's report and the various recommendations which it contains, will be obliged willy-nilly to examine once again and to answer the overwhelming question to which the main argument inexorably leads.

Previous page

Previous page