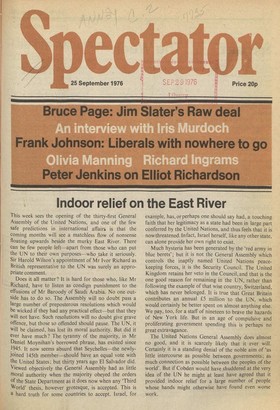

Indoor relief on the East River

This week sees the opening of the thirty-first General Assembly of the United Nations, and one of the few safe predictions in international affairs is that the coming months will see a matchless flow of nonsense floating upwards beside the murky East River. There can be few people left—apart from those who can put the UN to their own purposes—who take it seriously. Sir Harold Wilson's appointment of Mr Ivor Richard as British representative to the UN was surely an appropriate comment.

Does it all matter? It is hard for those who, like Mr Richard, have to listen as condign punishment to the effusions of Mr Baroody of Saudi Arabia. No one outside has to do so. The Assembly will no doubt pass a large number of preposterous resolutions which would be wicked if they had any practical effect—but that they Will not have. Such resolutions will no doubt give grave offence, but those so offended should pause. The UN, it will be claimed, has lost its moral authority. But did it ever have much ? The tyranny of the majority, in Mr Daniel Moynihan's borrowed phrase, has existed since 1945. It now seems absurd that Seychelles—the newlyJoined 145th member—should have an equal vote with the United States; but thirty years ago El Salvador did. Viewed objectively the General Assembly had as little moral authority when the majority obeyed the orders of the State Department as it does now when any 'Third World' thesis, however grotesque, is accepted. This is a hard truth for some countries to accept. Israel, for example, has, or perhaps one should say had, a touching faith that her legitimacy as a state had been in large part conferred by the United Nations, and thus feels that it is now threatened. In fact, Israel herself, like any other state, can alone provide her own right to exist.

Much hysteria has been generated by the 'red army in blue berets'; but it is not the General Assembly which controls the inaptly named United Nations peacekeeping forces, it is the Security Council. The United Kingdom retains her veto in the Council, and that is the one good reason for remaining in the UN, rather than following the example of that wise country, Switzerland, which has never belonged. It is true that Great Britain contributes an annual £5 million to the UN, which would certainly be better spent on almost anything else. We pay, too, for a staff of nineteen to brave the hazards of New York life. But in an age of compulsive and proliferating government spending this is perhaps no great extravagance.

The United Nations General Assembly does almost no good, and it is scarcely likely that it ever will. Certainly it is a standing denial of the noble aim of 'as little intercourse as possible between governments; as much connection as possible between the peoples of the world'. But if Cobden would have shuddered at the very idea of the UN he might at least have agreed that it provided indoor relief for a large number of people whose hands might otherwise have found even worse work.