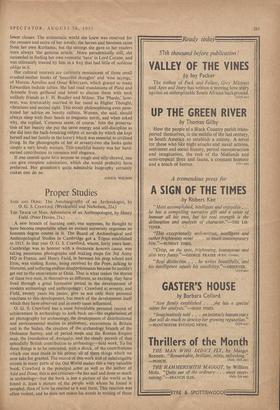

Proper Studies

SAID AND DONE. The Autobiography of an Archicologist, by 0. G. S. Crawford. (Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 21s.) THE TRACK OF MAN. Adventures of an Anthropologist, by Henry Field. (Peter Davies, 21s.) A new branch of learning may, one supposes; be thought to have become respectable when an ancient university organises an honours degree course in it. The Board of Archeological and Anthropological Studies in Cambridge got a Tripos• established in 1915. In that year 0: G. S. Crawford, whom, forty years later, Cambridge was to honour with a doctorate honoris causa, was taking panorama photographs and making maps for 3rd Army HQ in France, and Henry Field, in between his prep school and Eton, was visiting Rome, being received by the Pope, ,talking to Marconi, and suffering endless disappointments because he couldn't get out to the excavations at Ostia. That is what makes the stories of these two men, in themselves so different, so exciting; they have lived through a great formative period in the development of modern archaeology and anthropohagy : Crawford at seventy, and Field, twenty years his junior, give us not only their personal reactions to this development, but much of the development itself which they have observed and in many cases influenced.

0. G. S. Crawford has a most formidable personal record of achievement in archaeology to look back on—the exploitation .of air photography for archazology, the development of distributional and environmental studies in prehistory, excavations in Britain and in the Sudan, the creation of the archaeology branch of the Ordnance Survey, and of period maps and the Roman Empire map, the foundation of Antiquity, and the steady pursuit of that, splendidly British contribution to archteology—field work. To list these things is to be reminded, with a shock, of the contributions which one man made in his prime; all of them things which we now take for granted. The record of this work and of indefatigable travels in many parts of the Old World makes this a very valuable book. Crawford is the principal actor as well as the author of Said and Done; this is not criticism—he has said and done so much in archwology-but the book is less a picture of the world as he found it, least a picture of the people with whom he found it peopled, than of how he reacted to it and them. This reaction was often violent, and he does not mince his words in writing of those

in the Ordnance Survey and the Stationery Office who could not understand his enthusiastic advocacy of archaeology.

He stands out himself with all his likes and dislikes, finding the learning of Greek 'a futile labour' and that he was 'far less unhappy in the prison camp at Holzminden' than he was at Marl- borough, hating marmalade, tomatoes, dogs, and British hotels, liking smoked eels, pilaf with cuttlefish, Vichy water, liqueurs and good coffee, cats and detective stories, finding the Holy Sepulchre tawdry and vulgar, and the Spanish habit of dining at eight or nine p.m. in the winter 'definitely absurd.' The book is too long and its rigid adherence to diary form ('We took off at 6.15 a.m. and landed at Rutba Wells where I ate two complete breakfasts one after the other') and its inability to shed essentials, detract from its charm. But we forgive all this for its good stories and its constant peeps at a great man and his record of archeeological achievement. Salamon Reinach was once asked, perhaps at the height of the Glozel scandal, if he knew Crawford, and is supposed to have replied, 'Isn't that the man who saw something from a balloon?' This book tells us how much Crawford has seen from balloon and bicycle, and taught others how to see.

Henry Field is an American who was educated at Eton and New College, learnt his archaeology and anthropology at Oxford under Balfour, Marett and Dudley Buxton, and has spent his life in travel, archaeological reconnaissance excavation, and in organising some of the best-known galleries in the Field Museum of Natural History at Chicago. His book, The Track of Man, takes us to most parts of the world, from his childhood in Leicestershire to Kish and Jemdet Nasr, from caves in southern Spain to the Kremlin-and Central Asia, and it brings us into contact with the discoverer of Pithecanthropus erectus, with Sir Arthur Keith, Gertrude Bell, T. E. Lawrence. Most of all it deals with the Near East, where Henry Field has done so much of his work. Despite the fact, as we are told, that 'the original manuscript has been twice bisected,' it is still far too long, which will make it read more by professional archaeologists and anthropologists than by the general public. And the professionals may find some of the facts a little surprising. Field claims that the 'eight dramatic and colorful dioramas' in the Hall of the Stone Age of the Old World in Chicago were one of his major achievements, and he certainly spent much time, energy and money on them. But the datings he gives of two of them, the Curiae alignments to 6,000 BC and the Auvernier copper and bronze-using lake dwelling. to 5,000 BC could hardly have been seriously held by many competent archaeologists even in the Thirties. It is somewhat ironical that it is radio-carbon dating, developed at Chicago as a by-product of research into nuclear physics, which has in the last few years confirmed the inaccuracy of these dates.

GLYN E. DANIEL GLYN E. DANIEL

Previous page

Previous page