Cinema

Into the family business

Christopher Hudson

The Godfather (` X ' Paramount, Universal, Empire and ABC 1) is a film about the Mafia. It has grossed £20 million so far in America, on a production cost of £2i million and Paramount clearly expect it to go on to become the greatest box-office success of all time. The Daily Express and Daily Mail have been running rival serialisations of the book and screenplay; relentless advance publicity on London omnibuses and in Underground stations has blazoned "The Godfather is coming "; and the Evening Standard (or was it the Sun?) has instructed us to buy doublebreasted jackets with padded shoulders in homage to an irreversible trend in fashionable gangsterwear.

How can any film live up to such expectations? The Godfather is not a masterpiece. Instead it is a long (three hours), often exciting and always well-directed film about the struggle for survival of one of the five Mafia 'families,' the Corleones, in late 1940s New York. The rules are straightforward, although the conventions are complicated by Sicilian tradition. Absolute authority is wielded by the Don, the head of the family. He dispenses ' protection ' in return for favours. In so doing, he builds up a circle of powerful men — politicians, lawyers, police chiefs — who are in his debt. This enables him to provide swifter 'protection ' in return for favours extorted as much through terror as moral obligation. And if the ' family ' runs short, it forces its kind assistance upon the unwilling, in return for a share in the profits.

Naturally all this is fictional and takes place twenty years ago — despite which, a certain powerful organisation of American citizens made sure that the word ' Mafia ' wouldn't be mentioned. But in any case, Mario Puzo, author of the novel and partauthor of the screenplay, has whitewashed a very ugly monument of free enterprise. From the very first scene the moral ambiguity of The Godfather becomes apparent. A middle-aged man is pleading into the camera. Tears run down his face. He is telling us that his beautiful virgin daughter was attacked by rapists. Now she is in hospital, scarred for life, and the two boys have got off with three-month prison sentences. Will Don Corleone avenge her?

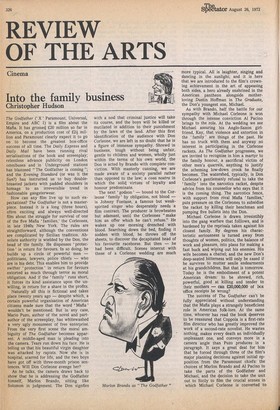

As he talks, the camera draws back to show that he is addressing the Godfather himself, Marlon Brando, sitting like Solomon in judgement. The Don signfies with a nod that criminal justice will take its course, and the boys will be killed or mutilated in addition to their punishment by the laws of the land. After this first identification of the audience with Don Corleone, we are left in no doubt that he is a figure of immense sympathy. Shrewd in business, tough without being unfair, gentle to children and women, wholly just within the terms of his own world, the Don is acted by Brando with complete conviction. With masterly cunning, we are made aware of a society parallel rather than opposed to the law; a cosa nostra in which the solid virtues of loyalty and honour predominate.

The next 'godson' — bound to the Corleone ' family ' by obligation, not blood — is Johnny Fontane, a famous but weakspirited singer who desperately needs a film contract. The producer is browbeaten but adamant, until the Corleones "make him an offer which he can't refuse." He wakes up one morning drenched with blood. Searching down the bed, finding it sodden with blood, he throws off the sheets, to discover the decapitated head of his favourite racehorse. But then — he had been difficult. Scenes intercut with these of a Corleone wedding are much more typical. All is laughter, singing and dancing in the sunlight; and it is here that we are introduced to the film's crowning achievement in the art of appeasing both sides, a hero already enshrined in the American pantheon alongside motherloving Dustin Hoffman in The Graduate, the Don's youngest son, Michael.

As with Brando, half the battle for our sympathy with Michael Corleone is won through the intense conviction Al Pacino brings to the role. At the wedding we see Michael assuring his Anglo-Saxon girlfriend, Kay, that violence and extortion in the 'family' are things of the past. He has no truck with them and anyway no interest in participating in the Corleone rackets. As The Godfather progresses, we are invited to recognise in him a martyr to the family honour, a sacrificial victim of other men's quarrels, anything to justify the scheming low-down crook he finally becomes. The watershed, typically, is Don Corleone's gentlemanly refusal to take the ' family ' into the narcotics racket, despite advice from his counsellor who says that it is the coming thing. The narcotics fence, with support from rival Mafia 'families,' puts pressure on the Corleones to subsidise the racket by killing their henchman and pumping five bullets into the Don.

Michael Corleone is drawn irresistibly into the gang warfare that folllows, and is hardened by the reprisals taken against his closest family. By degrees his characteristic seriousness is turned away from thoughts of women, politics, the balance of work and pleasure, into plans for making a fast buck and wiping out his enemies. His wife becomes a chattel; and the new Don's deep-seated bitterness will only be eased if he survives to mutter senile endearments at his grandchildren. But that is tomorrow. Today he is the embodiment of a potent American dream: to be shrewd, rich, powerful, good at killing and tender to their mothers — can E20,000,000 of box office receipts be wrong?

The success of The Godfather can't be fully appreciated without understanding that the Mafia plays a strangely beneficient role in American folk-lore. At the same time, whoever has read the book deserves to be reassured that Coppola is a first-rate film director who has greatly improved the work of a second-rate novelist. He wastes nothing, makes every death an individually unpleasant one, and conveys more in a camera angle than Puzo produces in a paragraph. It says a great deal for him that he forced through three of the film's major planning decisions against initial opposition from the Paramount chiefs: the choices of Marlon Brando and Al Pacino to take the parts of the Godfather and Michael, and the decision to take the unit out to Sicily to film the crucial scenes in which Michael Corleone is converted to

the philosophy of the vendetta. But for all Coppola's talent, it has to be stressed that the film is ambiguous to the point of dishonesty about the Mafia. Coppola apparently made one remark during the filming with which many audiences, less easily impressed than their American counterparts by the Mafia lifestyle, may sympathise — that he directed The Godfather so that he could get the capital to make films he really wanted to make.

Previous page

Previous page