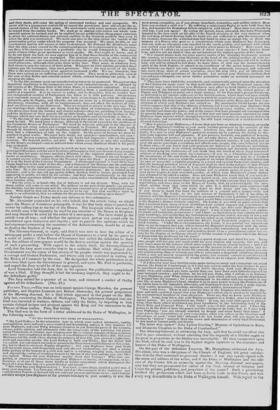

DIGESTED REPORT OF LAW PROCEEDINGS. 'Coma OF ClisNcsav. IN THE

ararrna OF Rvssztx, a bankrupt.—The question in this case turned upon the construction of the 56th section of the new Bankrupt Act. At the time of the bankruptcy, and for Some time before, there existed a contingent debt from

he bankrupt to the present petitioners. The occurrence by which the contin- gent obligation was to be turned into an absolute one, did not take place until after the issuing of the commission. The point therefore was, whether in these circumstances the creditor ought now to be admitted by the Commissioners to prove the debt. The Lord Chancellor decided the question in the affirmative. It was the first case which had arisen upon this subject. (Dec. 19.)

COURT OF KING'S BENCH.

THE KING V. MURRAY.—This was an indictment, preferred on the prosecutio

of Louis Celeste Lece:sne, against Mr. Murray of Albemarle Street, for a libel, contained in a work published by the defendant, and entitled " The Annals of Jamaica ; by the Reverend George Wilson Bridges, A.M., Member of the Uni-

versities of Oxford and Utrecht, and Rector of the parish of St. Anne, Jamaica." There was another indictment against the same defendant and for the same subject

matter, at the prosecution of a Mr. Eschoffery. It appeared that Messrs. Lecesne

and Eschoffery had been born and educated in Jamaica, and put forward in life there in the situation of merchants. Havir°e, become suspected of being con- cerned in an insurrection, they were arrested, under a law peculiar to that island, which authorized the Governor to transport beyond sea all such persons, being aliens, as he considered dangerous or suspicious. Their friends applied for a habeas corpus, and brought them before the Judges ; who thinking that there was sufficient evidence of the prisoners being British subjects, released theni from confinement. On some subsequent information, they were suddenly arrested, transported to St. Domingo, stripped of their properties, and separated from their wives ; and through the humanity of the master of an English vessel, obtained a passage to this country, where they had a petition presented to the House of Commons by Dr. Lushington. The evidence, which at the command of the House they produced of their being British subjects, was so satisfactory, that the Government undertook to compensate them for the injury they bad sustained by the deportation. It only remained to ascertain the amount to which they were entitled ; and pending the investigation of this part of the subject, was published the libel, from which the Attorney-General read a long extract. The prosecutors were called " the instigators of murder, rebellion, and revolution—impatient to bury their daggers in the breasts of the white population of Jamaica :" they were said to be convicted felons and conspirators, and to have imagined and produced the perpetration of all kinds of atrocities in Jamaica.

The case for the prosecution having been proved, Mr. Coleridge, for Mr. Murray, submitted to the Jury, that the defendant, a most respectable individual, pub- lished so many works that he could not read them all ; and that before the Jury should find him guilty upon the indictment, they ought to be satisfied that the publication was the result of malice on his part, or in other words, that his " mind had been at fault,"—a phrase which the learned counsel quoted from the great Lord Kenyon.

Lord Tenterden told the Jury, that it was impossible to conceive anything more outrageous than the language of this publication ; and that a glance at the pre- face would have shown the publisher the nature of the work. It was true that Mr. Murray published a great number of the most respectable and useful books that issued from the press ; but what was it to the Jury whether he published in a year four works or forty ? Whoever published libels, must be answerable for the consequences, as there would otherwise be no means of redressing so great an injury. The Jury immediately found the defendant guilty. The other in- dictment was not tried. (Dec. 19.) ANTI-CATHOLIC PETITIONS. DUKE V. POWNALL.—This action was brough to recover 219/. 18s. 10d., being the value of stationary supplied in January last to "the London and Westminster Protestant Association," which was formed about that time for the purpose of frustrating the machinations of the King, the Cabinet, and the Legislature, ad of preserving the integrity of the British Con- stitution. Of this association a standing Committee was appointed to sit con- tinually, "for the purpose of more effectually promoting the interests of the general body :" and the question in the present action was, whether Mr. Duke supplied his parchment and books' Rim. to the whole Committee of which the defendant was a member, or advanced the articles entirely on the credit of Mr. John Halcomb, the Honorary Secretary. The Jury found for the plaintiff; and Lord Tenterden said that Mr. Pownall would have his remedy against the rest of the Committee—who, by this defence, attempted, as Mr. Campbell observed, to saddle Mr. Halcomb with the whole of the expenses, of which 1,600/. remained unpaid after Mr. Halcomb had already defrayed 300/. out of his own pocket. Mr. Halcomb was produced as a witness for the plaintiff; and cut a figure in the cross-examination, and in Sir James Scarlett's speech for the defendant. It is unnecessary, however, for us to give any portion of the it11111COse details of the trial, which have all been for a long time notorious to the public. (Dec. 19.) Crum. CON. MvsKE-rr v. Gmaisv.—The defendant, Mr. Hanbury Gurney, is a member of the well-known banking firm at Norwich, and has represented that

city in Parliament. " He was formerly," as the Attorney-General stated, " a member of the profession called Quakers, but had since become a man of the world, and addicted himself to rural pleasures." He is a man of great wealth

and large estates. An action of the same kind was brought against hint by the same plaintiff in 1818, and tried at Thetford. The Jury, thinking the evidence insufficient to prove any criminal intercourse, found for the defeadant ; but the lady continued afterwardsto reside at her father's house,and altogether separate from her husband. About the year 1822, the acquaintance between her and Mr. Gurney, which had been discontinued from the period of the former trial, was again re- newed, and lately terminated in Mrs. Muskett's becoming pregnant by Mr. Gur- ney ; who removed her from her father's house in Norfolk to Montague Square, London, where she now lives under his protection. It was upon the ground of these latter events that the Attorney-General now claimed a verdict for the plaintiff. The learned gentleman anticipated any objections which may be derived from the separation of Mr. and Mrs. Mitskett, by citing some cases to prove, that notwithstanding the separation, the husband had a legal interest in the chastity of his wife. It was also a feature in this case, that the separation had been caused by the conduct of the defendant himself, who therefore was not in a condition to derive from it any arguments in his own favour.

Mr. Brougham, on the part of Mr. Gurney, addressed some observations in mitigation to the Jury ; who returned a verdict for the plaintiff, damages 20004 and costs. (Dec. 21.)

GOVERNMENT PROSECUTIONS AGAINST TIIE MORNING JOURNAL...--The first of these cases was an information filed er officio by the Attorney-General, against John Mathew Gutch, a proprietor, Robert Alexander the editor, and John Fisher the publisher, of the Morning Journal. The information in substance charged the defendants with having on the 30th of May last published a libel concerning the Lo, Chancellor and the Government, with the double ohject of defaming and traducing the character of the Chancellor individually, and bringing the Goverii. meat generally into hatred and contempt. The libel complained of was an article in which it was said to be insinuated that the Lord Chancellor had procured the appointment of Mr. Sugden to the office of Solicitor-General, in consequence of that gentleman having lent his Lordship a sum of 30,000/. The defendants all pleaded Not Guilty. The Attorney-General, in addressing the Jury, said, that considering the situa- tion which he filled, he could not allow the present publication to pass unprose- cuted, without leaving the characters of all persons of rank and honour in the kingdom exposed to the attacks of the same licentious description, and without appearing to sanction a notion which seemed to prevail pretty generally at present, that any man who had acquired any office or dignity under his Majesty became immediately a fit object of the abuse and contumely of his Majesty's subjects. The learned gentleman defined the liberty of the press as consisting in the right to print and publish whatever one had a mind, without any liability to censorship or supervision before publication. This doctrine, he said, had begun to be esta- blished soon after the Revolution of 1688 in this country, where exclusively it continued down to the present time. After stating that prosecutions like the present were calculated rather to establish than weaken the true liberty of the press, the learned gentleman said, that he must express it as his own opinion that the press of this country had enjoyed too much liberty for he last tea years, and that it would have exercised a greater influence upon the public if a little more of " wholesome correction" had been administered to it. After some other general observations of such a nature as are always made upon the prosecution side in cases of this kind, the Attorney-General came to the article which was the subject of the informa,ion.

" Mr. Sugden is to be Solicitor-General. The reasons which led to this promotion are really so natural that we beg leave to explain them, as Sterne would have done, by the mouths of I is inimitable Uncle Toby and Corporal Trim. Uncle Toby— If a pay- master or a barrackmaster lend money to his commanding officer, what should he ex- pect ?' Trim—"To be promoted, of course, your honour.' Uncle Toby— • If a captain, a tall, broad-shouldered fellow, for instance, who has married a rich dowager, should lend 10001. to his colonel, what does he look for ?' Trim—' To be made a major the first opportunity, and, as your honour knows, God bless you, to be placed in the way of higher preferment.' Uncle Toby—' And if a major should lend his general all his fortune, say 30,0001. for example, what then ?"frim—"fo be pla...ed in the general's shoes, your honour, before the end of the campaign.' This is, we admit, quite satisfac- tory. There Is reason in this merit, and there is point, too, in the argument, which Mr. Sugden and another learned person will be at no loss to comprehend."

This was the article which contained the insinuation concerning the 30,0001.; and to show that it must have applied to the Lord Chancellor, and that the writer wished to make the public believe that his Lordship was in great want of the money, the Attorney-General read the following article from another part of the same number of die Morrung Journal.

Let it stand over till next Session:—This Parliamentary cant term, which has been so constantly used by our procrastinating, vacillating Ministers, has lately been adopted in another hull -e, that of a great legal Lord and Lady, who are so much sought after by certain loud single-knock visiters, that the servants, to save themselves time and trou- ble, have hung up in the hall the following written answer :—' Let it stand over till the next session."

The Attorney-General said, that nobody of any reason and experience could doubt that the insinuation about the sale of the Solicitor-Generalship was false. But the publication had been undoubtedly read by many who were as foolish as the man who wrote it; and there existed a large body of persons whose opinions on public affairs were taken from newspapers alone. The business of the Jury was to decide whether the appointment of Mr. Sugden was the result of corruption or not. There was no reason to apprehend any danger to the liberty of the press as long as it was subject to no other control than what was exercised over it by enlightened Juries. Lord Holland, Lord Bexley, the Master of the Rolls, the Lord Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, Mr. Baron Vaughan, Mr. Courtenay, of the House of Lords, the Governor of the Bank of England, the Chairman of the East India Com- pany, and the Chairman of the Middlesex Magistrates, all deposed that they had read the article in question, and believed it to apply to the Lord Chancellor. Mr. Frederick Pollock, on the part of Mr. Gutch, contended that his client was entitled to a verdict of Not Guilty, on the ground that he had no immediate par- ticipation in the writing and publishing of the article in question, and had not at any time interfered in the conduct and management of the paper. Fisher, the publisher, made no defence. Mr. Alexander defended in his own person. He said that the Jury were perhaps not aware, that for the last hundred years there had not occurred an in- stance in which a defendant had been charged with writing a libel of which the object was to bring his Majesty's Government into contempt. The prosecution against him arose out a spirit of petty resentment, and had for its object to ruin his fortune, and perhaps to put an end to his life. The author of the letter ad- dressed in the year 1760, to the Duke of Grafton, (being the 12th in the series of Junius's Letters) had not been prosecuted by the Government of that day; nor the late Mr. Curran for a speech which he addressed to the Lord Chancellor and Privy Council of Ireland, on behalf of the Commons of the Corporation of Dublin. Lord Bolingbroke and Horace Walpole indulged in strictures still sharper and severer; and the Edinburgh Review used to contain, some years ago, severer articles than at present. The second general topic of Mr. Alexander's defence was, that the Government had at present no reason to fear either war from abroad or treason at home ; and that therefore the prosecution indicates in his Majesty's Ministers an arbitary and tyrannical spirit, as the article under prosecution was no more than a political quiz," and could not have appeared to anybody to be a serious production. The article, such as it was, did not refer to the Lord Chancellor at all ; and Mr. Alexander could have brought into the witness 'box noble and illustrious persons, of higher rank than any then in Court, who would swear that they did not think the Lord Chancellor was the "learned personage" alluded to.

The Attorney-General began his reply by arguing at some length against the law as it had been laid down by Mr. Pollock. He then said, that the facts stated by Mr. Alexander,—namely, that there had been no such prosecutions as the present for a hundred years, and that the present had been instituted through personal resentment,—were equally untrue. Informations ex-officio had been filed several times when Lord Eldon and Sir Vicary Gibbs held the office, and such prosecutions had only begun to be relaxed about the year 1818. But if the fact, as stated by Mr. Alexander, were true, the consequence which he had drawn would be entirely inadmissible; as the impurity of one libel was no reason why another should not be punished. The learned gentleman, after some reflection upon Mr. Alexander's want of acquaintance with history and grammar, and some observations intended to enforce the principal topics of his opening speech, left the case in the hands of the Jury. Lord Tenterden's charge contained nothing partimar. His Lordship said, that in reason and justice, as well as in law, the proprietor of a paper was as much answerable for the contents of it as the editor and that calumny, in whatever form it appeared, was liable to punishment. The Jury almost immediately re- turned a verdict of Guilty against all the defendants. (Dec, 22.) SECOND TRIAL.—This was an information agaiat the same defendants, and charging them with having, on the 14th of May, published in the Morning Jour. nal a libel upon the King and his Government, with intent to defame and degrade his Majesty, and to bring him into contempt with his subjects. The article com- plained of contained the following passage.

" His Majesty, it is said, complains bitterly that his Ministers have placed him in such a position that he cannot enjoy the pleasure of exhibiting himself to his people. George the Fourth was till now a popular monarch. That he has been rendered otherwise is the act of his imperious Minister. We deeply lament the occurrence; but public feeling is an ever-moving tide that is affected by causes, which, although invisible, often lead to disastrous results. We pity our aged and revered Sovereign. But there are sorrows which are too poignant to be relieved by the secret tear—they must be rendered torpid by other appliances. It is sufficiently obvious that there never was a more ambitious or a more dangerous Minister in England than the Duke of Wellington. But if his ascen- dancy over the Monarch be such as is represented—or rather such as it is represented to have been,—then we are sure that national sympathy must spontaneously flow toward the King. The people must feel intensely the restraints imposed upon the Sovereign, and regret that, overflowing with goodness as bets, kind to excess, fondly attached to his subjects, and paternally anxious to see them all prosperous and happy, he cannot mingle with their public entertainments, or receive those congratulations which most be grail. fying to his Majesty in the wane of existence. But his Majesty may yet have strength and intrepidity to burst his fetters, dismiss from before his Throne evil councillors, and assume that station in public opinion which befits a popular Monarch."

The Attotney-General introduced the subject to the Jury by some general ob. servations, such as would be made by any body who should read the article in question,—as, that agitation had become useless when this article was written ; that in all political discussions, the personal character of the King ought to be respected, &c. &c.

Mr. Pollock, on behalf of Mr Gutch, addressed to the Jury an argument of the same nature as that which he had used at the trial on Tuesday. Fisher, the publisher, declined making any defence.

Mr. Alexander again defended in his own person. He said that he was him- self a loyal subject, and faithful servant of the King. The article complained of was w ritten under great excitement. It had no tendency to bring his Majesty into contempt, as six months had elapsed since its publication, and it had not yet produced that effect. In consideration of the great benefits which the press conferred upon the public, they ought to show great clemency to its errors. The late Mr. Perry was acquitted for a libel of a much graver character than the present. The defendent had always spoken of his Majesty with the most pro- found respect ; and it was no libel to pity the King. Mr. Alexander stated, that he had been consulted as to the propriety of his Majesty's visiting the great na- tional theatres about that time ; and he (Mr. Alexander) advised the King not to go, lest he should be ill received by the people : his advice had been acted upon, and the King had, consequently, remained at home. So far as the article affected the Ministry, Mr. Alexander said that it only called them dangerous and ambi- tious ; and if the Jury should think this a libel upon the Administration, there must soon be an end to all freedom of political discussion in the country. The Attorney-General, in reply, said that if the press were now, as in the days of Addison and Steele, conducted by men of learning and virtue, no danger could be apprehended from giving it unbounded liberty. But when it was made the subject of traffic by ignorance and audacity, some corrective must be admi- nistered to an evil which would be otherwise too great for endurance. As far as the libel regarded his Majesty, the Attorney-General observed, that to represent the King as in a state which called for compassion, could not but be a gross libel. Even if the fact were true, it was adding to the degradation of the King to pub- lish it in a newspaper. After observing on the part which related to the Duke of Wellington, the Attorney-General distinguished the present case from that of Mr. Perry, whose explanation of his own language showed that he had been misun- derstood. With regard to the number of prosecutions against the present de fendant, they bore a small proportion to the number of libels which he had written Lord Tenterden told the Jury that the article was a libel, and that the defendants were answerable, although the libel may not have produced its intended effect. The Jury retired, and after three-quarters of an hour, returned the following ver. diet :—" We find the defendants guilty of a libel on his Majesty, but we do not find them guilty of a libel on his Majesty's Ministers. We also beg to state, it is our opinion that the article in question was written under feelings of very great excitation, occasioned by the unprecedented agitation of the time; • we therefore most earnestly beg to recommend all the defendants to the merciful consideration of the Court. (Dec. 23.) THIRD TRIAL.—This was another information against the same parties, for a libel published on the 16th June, and tending to degrade the King and bring his Government into contempt, and to inflame the minds of his Majesty's subjects against the Houses of Lords and Commons. The article itself follows.

"Mr. Sadler brought under the consideration of Parliament on Friday last, the dis- tressed condition of the manufacturing labourers of Blackburn, in the county of Lan- caster, who, to the number of 12,000 men, complain that they are reduced to pauperism, are struggling with starvation, and unable by the most excessive labour to earn more than Md. a-week. Did this picture of appalling misery excite the sympathy of Parlia- meat ? Did any honourable member who eats the taxes, or any right honourable epos. tate whose family revel on the spoils of a sinking nation,—whose brothers, sisters, uncles, and cousins, sap our life-blood, divide among them our possessions, fatten on sinecures, and are insolent under the charms of commissionerships,—did any of the people—bloated, corrupt, and dishonest as they are—offer the slightest symptom of com- miseration for these destitute men ? No! Mr. Peel was seen—we saw him—to smile at the tale of distress. Instead of blushing, he concealed his agony under an affected sneer. He laughed at the details of penury ; and he attempted to defend his system in a tone that would have been considered impious and heartless in a spinning-jenny or a steam- loom, But we have done with this now-fallen and despicable man. He is in that un- enviable position which it would almost be cruelty to endeavour to render, by any exposure, more pitiable or contemptible. For but a few moons longer can he be a Minister of the Crown. Events are ripening, which will overturn all his mischievous measures, and drive him into that obscurity from which we pray God, even for his own sake, he may never again emerge. We would, indeed, advise Lim to emigrate, and seek an asylam among the kangaroos and Peels of the Swan River. "But return we now to the distress of the country. There are some poor hirelings who live in London—place-hunters, of course—creatures that prey at the doors of the Treasury—paltry scribes who have not an idea beyond that of a spaniel who cringes be- fore his master—there is a leash of such hirelings, we say, who are impudent enough to assert in the public papers, and in ink not more black than their own hearts, that our distress is temporary—that it is caused by the speculations of 1821—and that a steady persistance in our present policy will ere long bring us relief. These men—if they be men—have the hardihood to !assert that our sufferings are not so great as they are re- presented to be. They endeavour to convince us that our evils are exaggerated—that the wages of labour are higher than the public believe—and that our leading interests, like the flowers of summer, are retarded by uncongenial weather, not destroyed by a mortal blight. They tell us that patience is all that is required to overcome the prevail- ing distress, and that Providence will come to our aid at the twelfth hour, according to the predictions of Mr. Peel, Mr. Huskisson, and his Majesty's Ministers. " Our reply to these persons is,—we trust in Heaven, but to the King's servants. We expect relief from the nation, not from the present Ad ration. Their blun- ders will cure themselves. Their errors will work their 0., ,,argation. The storm that is approaching will sweep them, their toad-eaters and th.. principled partisans, Into oblivion. Relief we musthave ; but we expect it not—we Ne,k it not from the Duke of Wellington or the present Parliament. The present apostates must pass through the Me to Noluch■-they meat be anuibilated—and then' co the wreck of their names and their deeds, will come the spring of renovated verdure and real prosperity. We never will be a prosperous nation till we repeal the pernicious laws and revoke the ac- cursed system of the last ten years. We must starve until every measure of the liberals be erased from the statute books. We must go to eternal ruin unless our whole com- mercial system be revised, and we be enabled, byour artificial but cheap paper-currency, to place the nationaldebtor and national creditor in the identical position they were in when the debt was contracted. We must also give to the ship-owner the benefit of the preservative policy under which his property was invested. We must do this, or our commercial marine will sooner or later be destroyed. Mr. Peel and Mr. Huskisson argue that the ship-owner cannot be the embarrassed person he is represented to be, because, say they, if his business were not a profitable one he would relinquish it. This argu- ment evinces either great ignorance or cruel apathy. Mr. Peel ought to know, and, if he do not know the fact, we now apprise him of it, that three-fourths of the commercial shipping of the country are mortgaged. The nominal owners, or, in other words, the mortgaged owners, are compelled, even at inadequate profits to sail these ships. They Must persevere, although ruin stare them in the face. They must, at whatever loss, find means to pay the interest of their debts. Whatever be their returns, provided those returns pay the mortgagee, they must persevere. This is the real secret of the trade. This is the mysterious cause of an apparent increased traffic. We say, therefore, that these men cannot go on suffering and losing for ever. They mist be protected, even at the cost of that Baltic and colonial system which, without benefiting one party, is de- stroying the other. " In the like manner must our manufacturing interests be protected. The pretext that improved machinery is the temporary cause of our embarrassments, as is affirmed by the cousin of Mr. Thomas Peel of the Swan River, is a miserable subterfuge. It is con- temptible in a Minister, it is despicable as coffin- g from a professed statesman and political economist. It is an excuse so paltry, and so desperate, that we wonder how any independent member of Parliament can listen to it with patience. Steam-looms may supersede manual labour. But what have steam-looms to do with the silk-trade ? Sarcenets, gros de Naples, and ribands, are not yet wove by a 20-horse-power engine. Machinery, therefore, with all its improvements, does not affect the weavers of silks. And yet these persons are distressed. They are steeped in misery to the very lips. They are starving—their children are dying from the want of sustenance—they receive no education even from the Sunday and charity schools—they are perishing from hunger ; and the skeletons of their parents lift up their hands, and repine at the destiny of Pro- vidence which has cast their lot in a country so heartless and uncharitable as this is.

" To the root of the system which has 'Produced this misery the axe of the reformer must be laid. We must have a change, although it should be caused by the abolition of the Commons House of Parliament. We must be relieved, although at the expense of Westbury and every rotten and corrupt borough in.England. We must have bread, though St. Stephen's, and all the Stephens, should suffer martyrdom in Smithfield. We have had a redundancy of talk on the subject. By the grace of heaven we must be purified by good works. We must have deeds, not speeches—amelioration, not cant— relief, not drowsy sermons, delivered by old hacks and hypocrites who eat the public revenue. We demand justice, not pity. We claim our rights as men who contribute to the King's exchequer—no; as debased fools whom every charlatan thinks it his privi- lege to despoil. " This is the lamentable condition to which we have been reduced by the most un- principled Ministers and the most heartless philosophers that ever disgraced any country. For the last few years we have not had a Minister of the slightest pretensions to elm- racier or consistency. Dragoon officers direct civil affairs. Troopers are our lawgivers. A cavalry cornet writes orders from the Treasury upon the Bank. A commissary-gene- ral is at the head of the Colonial Department, A discharged colonel is Lord Privy Seal. Drum-head law is the order of the day; and a General of the Marines has the patronage of high offices in the legal profession. As for our revered Sovereign—but we stop !—we pity him I He is the worst-used man in his extensive dominions. He is bullied by his servants; and in his ripe old age openly defied, derided, held in chains, prevented from appearing in public, insulted by his serviles, and kept most sacrilegiously in the dark upon all those questions which a generous, ajust, and a constitutional King ought to be most familiar with.

" But the crisis is at hand—the day of delivery is not far distant. Time, with his sharp scithe, will come to our relief. No artifices on the part of the quacks can prevent the terrible, but the necessary and the wholesome consequences of an unavoidable reac tion. Who shall be first cut down it is not for us to say. But that sacrifices must be made is so self-evident, that we refrain for the present from dwelling upon them."

Neither Gulch nor Fisher made any defence to this information.

Mr. Alexander contended on his own behalf, that the article being an attack upon the House of Commons principally, it was for that body alone to punish the writer by calling him to the bar of the House. The language which was used in the article may with impunity be used by any member of the House in his place, and may therefore be used by the editor of a newspaper. The facts statedv the article were all true; and whether the opinions were just or not, could only be ascertained upon discussion and inquiry ; and to punish the opinions which he had expressed concerning the measures of the Administration, would be at once to destroy the freedom of the press. The Attorney-General, in reply, said that it was new to hear the editor of a newspaper prefer a trial before the House of Commons to a trial by his peers in a court of justice : if the House of Commons had called the defendant to their bar, the editors of newspapers would be the first to exclaim against the severity of such a proceeding. With regard to the article itself, the Attorney-General said, that the Jury must consider that to be a seditious libel which alleged that Government was the cause of the misery of the people, which was augmented by a corrupt and bloated Parliament, and whose only cure consisted in cutting up the House of Commons by the root. He designated the whole publication as an atrocious libel upon the Government in general, and upon Mr. Peel in particular, and noped the Jury would be of the same opinion.

Lord Tenterden told the Jury, that in his opinion the publication complained of was a libel. If they thought it had the tendency imputed, they ought to fin the defendants guilty.

The Jury retired for a quarter of an hour, and returned a verdict of Guilty against all the defendants. (Dec. 23.)

Fouarit TRIAL.—This was an indictment against George Marsden, the present publisher, and Stephen Isaacson and Robert Alexander, the present proprietors of the Morning Journal, for a libel which appeared in that paper on the 30th July last, concerning the Duke of Wellington. The indictment charged that the libel was intended to traduce, defame, and vilify the Duke, by imputing to him certain disloyal designs and projects against the King and the succession to the Throne of these realms. Plea, Not Guilty.

The libel was in the form of a letter addressed to the Duke of Wellington, in the following words.

"TO IDS RICHNESS TIIE DUKE OF WELLINGTON.

"My Lord Duke,— In the miserable state to which your united ignorance, vanity, and ambition, have reduced a once-exalted and flourishing nation, it only remains for your Highness, and your Whig Attorney-General, to put down the press of the country, silence public opinion, and ultimately stifle the complaints of the surviving but perse- cuted Protestants of Ireland, now weeping over the murdered remains of those relatives who have been slaughtered at the shrine of yourHighness's Popish Relief Bill. Did your Highness tell the truth when, during the progress of that hill, you assured a right reve- rend and venerable prelate (the Lord Bishop of Bath and Wells), that the Relief Bill (so called) was calculated not only to preserve the Protestant establishment of this coun- try, but in short to overturn Popery altogether ? Did your Highness from your heart tell the truth when, with despicable cant and affected moderation, you drew a pretty little picture of the horrors of a chit war, and in a whining, weeping tone, deprecated and abjured the notion of crushing treason by the law of the land mid the bay. net? Oh! yes, indeed. When did your Highness acquire these fine feelings ? Who ever sus- pected, or whoever presumed to accuse your Highness of mercy, of compassion, of mo- deration, or of any of those more kindly or tender sympathies which distinguish the heart of a man from that of a proud dictator and tyrant ?

"But what has your Highness done ? You have, as you allege, avoided a civil war. I deny your assertion. You have put off the evil day—the conquest of the traitorous and confederated Papists of Ireland did not suit'your present ambitious views,- and I hereby

publicly arreiga your Li/gluten of the grossest treeclicry to your =nary, or else the

most arrant cowardice, or, if you please, treachery, cowardice, and artifice united. How have you avoided a civil war ? By suffering a sanguinary Papist to isshe forth from his den, and murder his Protestant fellow-subject in cold blood 1 How have you avoided a civil war, I ask you again ? By seeing the decent, loyal, educated, free-born Protestant Impaled to the very earth on the pike of the Popish assassin, at the very moment when the last drop of blood flowing from his heart was not sufficient to glut the vengeance of his enemies, because the wretched man had dared to wear an orange lily, or drink the memory of a Prince who gave us a constitution which your Highness has destroyed. And yet, with an effrontery only equalled by the fraud, perfidy, and tyranny with which you carried your relief bill, you say you have given peace to Ireland ! Now, mark me, proud duke—I called you so once before—I know your objects—I have known them long, and it is not my fault if they are not known in the highest quarter of this land. " If it should please God, for some special marks of his Almighty displeasure against this country, to continue your Highness at the head of the Administration of your be- trayed and deceived Sovereign, you will find that in the end (and that end will be before long) you will be obliged to put down by main force of civil war the insurrectionary spirit of the Irish Papists, or submit to an overthrow of the union between England and Ireland—an object not only contemplated, but projected, arranged, and matured Into every thing short of actual execution, since the year 1514, and all through the instrumentality and operations of the Jesuits. Let me tell your Highness further, that you andyour colleagues can never shelter yourselves under an assumed ignorance on these points. " They have been faithfully, ceaselessly, and energetically pressed upon the attention of the Cabinet for many years by that most able advocate of the Protestant cause—Sir Harcourt Lees ; and, however your Highness may affect to think lightly of the political knowledge of my learned and dearly valued friend, yet I defy the united powers of Popery and Whiggery to point out a single instance of Sir Harcourt's prognostications, as delivered in his various addresses to the British nation, which have not been strictly and critically fulfilled, from the first hour in which his penetration and sagacity prompted him to employ his deep learning and researches in defence of his King and of that con- stitution of which your Highness has robbed us. My inestimable friend knows me too wen to suppose that this is the effusion of flattery, bat I can inform your Highness that in every page of his writings there will be discovered an exact outline, as in a map, of our foreign and domestic policy, and of the causes that have plunged our commerce into its present deep state of ruin, as well as of that last and fatal measure executed by your Highness front motives which, though longsince known to some, are now more distinctly seen through, and narrowly watched by, the still loyal subjects of a kind-hearted but ill-used Sovereign. " May it please your Highness,—I know that you have an Attorney-General, as ready to do your Highness's bidding as your noble brother possessed in the services of the notorious William Conyngham Plunkett. I believe too, that whether justly or un- justly, it is now in your Highness's power to immure me in a prison for daring to dis- pute your supreme will and pleasure. If you possess, however, one particle of honour, bravery, loyalty, or justice ; if you be not actually driven to insanity by the reckless ambition which characterises your well-known and ulterior objects; if you wish now in your old age to conciliate a confiding and affectionate people, who once believed you to be their own,—if you know that your projects are known t6 an illustrious individual, whom you permitted to be vilified, traduced, calumniated, and defamed, without even once denouncing his traducers —if you think that the blood of those loyal murdered subjects of the King cries aloud for vengeance,—if you be a Christian,—if you know Site uncertainty of life and death—that you are but a man—that you may he a kindred to the worm before you can wield the sceptre of an infant Princess—that this infant has (in case of necessity) a rightful guardian in a royal and exalted Protestant relative, aml that the best and proudest blood of England shall be shed in the defence of that Prince and his Royal House—if, Duke, if, I Bay, your Highness knows that these things are so, or may be so ; then, in God's name, I conjure you to restore peace, if peace be yet in your power to give, to that wretched country, of which your Highness's vanity makes you ashamed to be called a native. Does notyuur Highness know that, if you ever de- served the name of a brave soldier, or an honest man, you could not take a more just or likely method of retaining these invaluable gems in your coronet than by coming for- ward boldly, and like a man, in the House of Lords, and, by acknowkalging the mis- chiefs arising from that error which (to give it a mild name) your ignorance had. led you to commit ? Why not come down to that house and say, like a man, if you mean to stand free from the epithets of a coward and a tyrant,—why not honestly say, lily Lords, in the late session of Parliament I felt it my duty, in common with his Majesty's Government, to recommend for your Lordships' sanction and adoption, a measure which I sincerely hoped would have restored peace and tranquillity to his Majesty's Roman Catholic subjects. My Lords; it was with no small satisfaction that I received from many of your Lordships your cordial support and concurrence in the object which I desired to promote ; but, my Lords, (qu. does your Highness under- stand Latin), nil humani alienum a ins pato. I was in error to be sure ; ' est sapien- tis errare sed insipieutis perseverare ;' and I have no hesitation in now coming down to your Lordships, and saying that my unfortunate project has ended, not only in not pan- fling or conciliating the Irish Papists, but has acted as an incitement to these insurrec- itionary traitors to waylay and murder the King's loyal Protestant subjects in that ill- fated country. • Under these circumstances, my Lords, it is a painful but incumbent duty on me to request that you will re-invest his Majesty's Government with the privi- leges of that constitution which we have so awkwardly surrendered, and that in your wisdom yote will consider a cruel and revolting death to be a punishment rather too se- vere for the display of an Orange riband, or forthe avowal of principles which the House of Bruuswick has professed for 141 years.'

" Now your Highness will perceive here a speech ready cut and dried for you. To be sure, people will not give you much credit for your wisdom and sagacity, but you will gain much more by the balance which must remain i tu favour of your honesty ; and I do believe that, however late you may appear on the gromni in this act of justice and in- tegrity, you will ultimately do better for yourself, and for the noble palace which you are now constructing, than in running any risk to encounter a desperate ambitious measure which is now not merely suspected by the public but actually canvassed and discussed in every political conversation. It would be idle in me to suppose your Highness was ignorant of my meaning. "If I discover your base hireling Dress again daring to insult and calumniate my royal master, the Duke of Cumberland, or if I find you even to suffer the foul libellers to pass by unnoticed and unpunished, I will, with God's blessing, hold your Highness up to public view, and unmask you more openly than you have been even hitherto exposed to your betrayed country; and further, let me tell you, Duke, that I will do so in defiance of your Highness, your Whig Attorney-General, your whole cabinet, and the Popish mob of Ireland into the bargain ; for I on determined to try either with the sacrifice of my own life, or your Highness's head, whether it be in your power to keep the Protestants of my native land in the degraded, miserable, and humiliated state to which, I again repeut, 'your vanity, ignorance, treachery, ambition, and artifice, have reduced them.' One word more. There is not a sensible man in the kingdom who believes the flip- pant and well-contrived report that your Highness's eldest son is about to be married to. the accomplished daughter of your physician. Trust me, that we know your Highness too well. Long, long since, has your Highness aspired to a higher prize far the heir of Apsley-palace. Do you understand me, Duke ? If not, my next shall speak in plainer terms than those which bewildered my Lord Lyndhurst in the interesting story of My Uncle Toby and Corporal Trim. I will watch you,—I will unmask you. I have the power to do the first—I have the power and the courage to do both; but, as I once told your Highness you are already watched by deeper and wiser heads than mine.' I leave you to the consolations of your conscience, while you reflect on the blessings and advantages of your 'relief bill,' although I do not know what bill you mean to in- troduce to 'relieve' yourself from the scorn and detestation of every loyal Protestant in this laud of former pride and liberty.

The letter was signed" John Lytton Crosbie," Minister of Sydenham in Kent, anti Domestic Chaplain to the Duke of Cumberland."

The Attorney-General, in addressing the Jury, said that he could not allow this libel to pass unnoticed, without admitting that the impunity of a libeller ought to be great in proportion as the libeller was incorrigible. He then commented upon the libel, which he said was in the highest degree injurious to the character and honour of the Duke of Wellington.

On the part of the defendant Isaacson, Mr. Humphreys addressed the Jury. His client, who was a clergyman of the Church of England, felt great satisfac- tion that the libel contained no personal slander: it was also openly signed with the name and address of the writer, and if the Duke of Wellington and the ofli- cers of the Crown felt no animosity against the Morning Journal newspaper, why had they not prosecuted the author of the libel, instead of bringing into Court the printer, publisher, and proprietor of the paper ? Such a proceeding falsified the professions which had been so lately rnade in that Court, and was every way dkreditablo to the Duke of Wellington, himself. With regard to alit publication complained of, it imputed to the Duke of Wellington a design to marry his son to a Royal Princess. Now Mr. Humphreys thought, that such a marriage, if effected with the King's consent, would be a legal act, and that there- fore there was no libel in imputing to any body a desire to promote it. As to the other parts, was it a libel to accuse a man of ignorance, vanity, and ambi- tion ? or would it be now called libelous to charge a government or a minister with having attempted to overthrow the Constitution of his country ? If such charges were libellous, then would it appear that libels almost inaumerable had been lately pronounced in both Houses of Legislature, by some of the most eminent persons in this country. The individual who was the author of the libel was excited by every motive which could stimulate a man in such circum- stances. He was a minister of the Church which he believed the measures of the Duke of Wellington would destroy ; he was the Domestic Chaplain of a Royal Duke, against whom charges of the most horrid nature had been made by one portion of the press, without any interference on the part of the Duke of Wellington or his Attorney-General; and he wrote the publication in question at a period of unparalleled excitement, and with the haste attending a newspaper composition. The learned gentleman hoped, that the Jury would agree with him in thinking that the article in question contained nothing which exceeded the limits of fine and free political discussion.

Mr. Alexander said, that as the signature, address, and description of the author was attached to the letter, the Duke of Wellington might have had the Domestic Chaplain of the Duke of Cumbelland before the Court, if the present had been anything but a most scandalous attempt to ruin him (Alexander) and destroy the liberty of the press.

The Attorney-General, in reply, said, that the Duke of Wellington would. be most happy to prosecute Mr. Crosbie, if such a person existed, and the Duke had the means of bringing home the publication to him. But Mr. Crosbie bilciself had not come forward, and the defendants had offered no assistance-towards bringing him into Court. With regard to the Duke of Cumberland, there had been no prosecution of the attacks on him, because his Royal Highness himself never made them the subject of any judicial proceeding, nor ever applied to the Government on the subject, though no man had better legal advice. The cause which the Jury had to decide was the cause of the people of England ; for should the time ever come when Juries were fearful of incurring the anger to the press, then would be the commencement of tyranny and an end of the reign of justice.

Lord Tenterden told the Jury, that in his opinion the publication complained of was a libel of a slanderous and calumnious nature. In reference ;.o the charge made against the Attorney-General of a desire to destroy the freedom of the press, his Lordship said, that he thought there was no ground for the charge, and that he had only done his duty in endeavouring to repel licentiousness and punish calumny.

The Jury, without looking at the libels, found all the defendants Guilty.

THE KING V. BELL,--This was an indictment against the editor of the Atlas, for a libel in which he charged the Lots' Chancellor, with having bartered the pre- sentation to ecclesiastical livings, of which a great many are in his patronage. The libel commenced in the following words:— " There were rumours in the highest political circles last "night, that a certain noble Lord, holdings a situation of vast responsibility, and who is said to be on terms of dis- agreement with another of his Majesty's advisers, has been charged with bartering eccle- siastical livings. His Lordship's friends disbelieve the imputation and repel it strongly ; whilst they intimate that the dealings in the wages of clerical advancement have been ran sacted by his lady without his Lordship's knowledge."

When it was formerly intimated that Mr. Bell derived his information from another, he was informed, that if he would give up the author, so as that the Lord Chancellor may he able to trace the calumny to some known source, the present proceedings woad be immediately dropped. This offer was now repeated, and declined.

Mr. Bell began his defence by thanking the Attorney-General for not mixing up his case with that of the person who had been lately before the Court, and with whom he did not wish to be associated. He could not give up the name of the person who furnished him with the information, as it had been given in confi- dence. The article was written very late at night, and given to the printer in a great hurry, and with so much inadvertence that it could not be regarded as a malicious publication. Mr. Bell had no personal or political dislike to the Lord Chancellor; on the contrary, both himself (Bell) and Mr. Whiting, a proprietor of tke Atlas, entertained the highest respect and esteem for his Lordship. The Jury were by their verdict to decide whether the editor of a newspaper was or was not at liberty to give insertion to a rumour which occupied all the rest of the public. The returning a verdict of guilty in the case would be an unmerited punishment upon him, whilst it could not do any.advantage to the reputatiou of the Lord Chancellor ; whom the public and the defendant considered as utterly incapable of the conduct imputed to him in that rumour.

Lord Tenterden told the Jury, that to barter ecclesiastical livings for money, was a serious and criminal act ; and that to impute such bartering to any person whatever, was a libel. His Lordship said, that the fact of a calumnious rumour being very generally circulated, was no excuse for an editor of a newspaper who should give it insertion in his paper. The defendant had quoted Lord Ken- yon's saying that a libel published without advectence was not a libel: Lord Tenterden had often heard Lord Kenyon express his opinion on the subject, and he could say that Lord Kenyon had never said that a man should not be liable to punishment for his acts, merely because they had been inadvertently committed. The Jury retired, and were absent half an hour. On their return, the foreman delivered the verdict to this effect—" We find the defendant Guilty of having pub- lished the libel; but, as a doubt exists as to his having published it with a mali- cious intention, we beg leave to recommend him to the merciful consideration of the Court."

The Attorney-General—‘‘ Gentlemen, I beg to assure you that I receive your verdict with very great satisfaction ; and I have no doubt that the Lord Chancellor, to whom I shall communicate it, will receive it with a similar feeling; and that it will be acted upon in favour of the defendant, who conducted his case in a man- ner which I think highly creditable to him, and with great talent, discretion, and good feeling." (Dec. 24.)

Previous page

Previous page