THE SCOTTISH ANNUAL.

OUR last week's gratulation as to the probability of having looked our last upon the Annuals, was premature. The ink of our lo triumphe was not dry (for most probably the types had not been

imprinted) ere another of the family was placed upon our table; differing, however, from the generality of its class in several and

obvious points. It is produced in another kingdom ; it repudiates• all attempts to found an extrinsic claim by the assistance of the engraver,—relying "more on the reader's sense than the gazers eye;" and its writers, with some few exceptions, are names unknown to Annual fame. A circumstance that gives a not unfavourable character to its literature; which has more freshness, ;natter, and reality about it, than many of its grander London rivals ; at the same time that it wants that formal kind of merit which springs• from a mechanical imitation of patterns. The most curious thing in the volume is a letter from Miss EDGEWORTH to WALTER SCOTT—" act Scotus out Diabolus," as the letter commences—on the first publication of Waverley. It is not only singular as showing how quickly the penetrating female divined the author—good for its criticism upon the work, and interesting for its description of the impression made by the novel upon the family-eirele of tl.e EDGEWORTHS—but it derives a naive kind of charm from its account of the manner in which the complimentary " Postscript that should have been a Preface " happened to be read at all. The editor's paper, entitled " Con- fessions of a Novel-reader," has point and humour; though the subject is overlaid by the minuteness of its treatment. his story of" The Tinker " is a good exhibition of character, and presents a slight but graphic picture of Scottish life at the commencement of the last century ; but an undue admiration of Professor WiLsole's rhapsodical style of description, has induced Mr. WEIR to en- cumber the opening of the tale with "passages that lead to nothing." "My Grand-Uncle's Bequest," is apparently by GALT : at all events, it is in the style of GA vr's best days,—full of humour, character, incident, and satire, not only on the inhabitants of a Scottish town, but on no less a matter than the Roxburgh Club. " The Knout" is a plain but distinct account of the manner of in- flicting this horrible punishment; and there are several other amusing mis: ellaneous papers, both in prose and verse. In say ing that the Scottish Annual disclaimed the assistance of the engraver, the meaning must be limited to what are called pic- tures. The autograph illustrations not only give a character to, but form a feature of the work. The author of this department, when at Paris, attended Dr. GALL'S lectures : it was the habit of the Founder of Phrenology to make a subject of any of his auditors, pointing out a person who was largely gifted with the particular

organ he was discussing : our friend was favourably noticed for his "Causality :" after the lecture he introduced himself to Dr.

GALL, and was invited to dinner ; and the owner of this well-de- veloped philosophical organ bad the honour of meeting SPURZ- HEIM, DUPUYTREN, and CUVIER. After dinner, they discussed

the point of "how far the character of a man's mind can be sur- mised by any other physical signs than those which phrenology furnishes :" and the sages decided, that three other modes, though

not infallible ones, existed,—physiognomy ; pathognomy, meaning

"natural language," or, in other words, gait and bearing • and autographology, or the art of diviuing characters by the Land-

writing. " The conversation noe;'11Arned upon this theme ;" the

present writer was made acquainted t6ith the rationale of the sub- ject; he took to collecting autographs, and has furnished the cream of his selection for the use of the Scottish Annual. These speci-

mens are numerous and various, extending from Madame VESTRIS up to GEORGE WASHINGTON : they consist not of mere signatures, but generally of entire letters; and to each of them are appended scientific disquisitions,—sometimes, oonfining the exposition of character to the handwriting only,, sometimes making the auto- graph a mere cue to speak fully of the person. We subjoin a specimen of each sort.

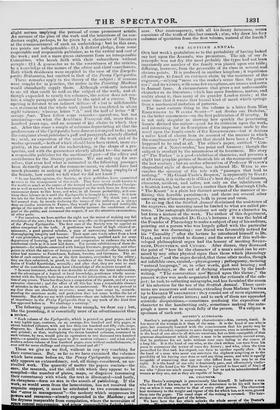

SOUTH EY'S AUTOGRAPH.

Southey's autograph is eminently characteristic—fine, correct, timid. It has more of the woman in it than of the man. It is the hand of one who is pure, but constantly haunted with the consciousness that his purity may be sullied, and therefore repulsive to more daring natures, even to intolerance. It is the hand of one alive to all delicate emotions, but so little susceptible of that generous abandonment which allows a man to be momentarily carried away, that he performs his set tasks without ever once failing in the course of a long life. It is the hand of one who, as the clock strikes, can turn from his poem to commence the review of suite dry history ; and who, when the time prescribed for that task has elapsed, can turn to another equally alien. It is the band of a man who never can entertain the slightest misgiving as to the possibility of his having ever done or said any thing amiss, and who is equally incapable of conceiving that any one who differs from him may be in the right. It is the hand of one who is femininely pure, and effeminately vindic- tive. It is the hand (as Sir Walter Scott is reported to have said of him) of one who "lives too much among women." Let us not be misunderstood—Of women as they are, not as they are capable of being.

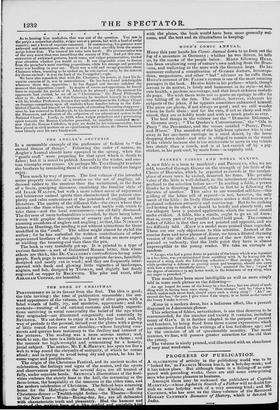

DR. C ',MERL

The Doctor's autograph is preeminently like himself. It indicates a man who has a will of his own, and is never so determined to let his will have its way as when it runs counter to that of every other person. The characters bear testimony to the weight and vigour of the fist which has, as it were, graved them into the paper. The usual slope of the writing is reversed. The hair- strokes are the thickest part of the letters. •

We have here the key which unlocks the whole secret of the Doctor's As to hearing him unshaken, that was out of the question. VOL( taw in the pulpit a somewhat shabby, vulgar sort of a person, but with a head of awful capacity, and a brow of supreme command. In commencing, his gestures were awkward and monotonous, the more so that he read slavishly from the manu- script before him. The tones of his voice were harsh. His pronunciation was of the very worst that ever issued from the county of Fife. And yet this con- catenation of awkward gestures, harsh tones, and vulgar pronunciation, riveted your attention whether you would or no. It was impossible even to dissent from the preacher's most startling propositions, while his strange and powerful voice was knelling in your ear. 'I here was a wild and savage grandeur about Chalmers when, warming as he rushed on, he was carried away by the interest dais theme excited : it was the bark of the Evangelist's eagle.

We have also remarked, that with Dr. Chalmers, his power, at least his fa- vourite exercise of it, was in contradiction. lie has been found indefatigable wherever there was opposition : he has flagged and become indolent the moment that opposition ceased. In despite of sneers and opposition, be forced leave to organize his parish of St. John's as he pleased ; and the moment his opponents had yielded, he set off to " Christianize " the Moral Philosophy chair in St. Andrew's. At that University he involved himself in a dispute with his brother Professors, because they made attendance in the College Chapel on Sundays compulsory upon all students whose families belong to the Esta- blished Church, and himself set the example of attending Dissenting clergymen : since he has removed to Edinburgh, he has become a most vehement assailant of the Dissenters, and advocate of the subjection of our educational system to the National Church. Lastly, in 1819, when vulgar prejudices and a persecuting spirit towards the Roman Catholics prevailed, he manfully combated them : now that the Roman Catholics, in part no doubt by his instrumentality, have been placed in civil matters on an equal footing with others, the Doctor laments .most placed over his own haudywork.

Previous page

Previous page