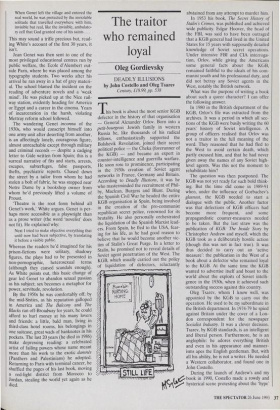

The traitor who remained loyal

Oleg Gordievsky

DEADLY ILLUSIONS by John Costello and Oleg Tsarev Century, ┬Ż18.99, pp. 538 This book is about the most senior KGB defector in the history of that organisation ŌĆö General Alexander Orlov. Born into a petit-bourgeois Jewish family in western Russia he, like thousands of his radical fellows, enthusiastically supported the Bolshevik Revolution, joined their secret political police ŌĆö the Cheka (forerunner of the KGB) ŌĆö and became an expert in counter-intelligence and guerrilla warfare. He soon rose to prominence, participating in the 1930s creation of Soviet agent networks in France, Germany and Britain. According to Deadly Illusions, it was he who masterminded the recruitment of Phil- by, Maclean, Burgess and Blunt. During the Spanish Civil War he headed the entire KGB organisation in Spain, being involved in the creation of the pro-communist republican secret police, renowned for its brutality. He also personally orchestrated the liquidation of the Spanish Marxist lead- ers. From Spain, he fled to the USA, fear- ing for his life, as he had good reason to believe that he would become another vic- tim of Stalin's Great Purge. In a letter to Stalin, he promised not to reveal details of Soviet agent penetration of the West. The KGB, which usually carried out the policy of liquidation of defectors, reluctantly

abstained from any attempt to murder him.

In 1953 his book, The Secret History of Stalin's Crimes, was published and achieved wide publicity. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, was said to have been outraged that a KGB general had lived in the United States for 15 years with supposedly detailed knowledge of Soviet secret operations. Under intensive FBI and CIA interroga- tion, Orlov, while giving the Americans some general facts about the KGB, remained faithful to the ideals of his com- munist youth and his professional duty, and did not betray any Soviet agents in the West, notably the British network.

What was the purpose of writing a book about such a queer character? I can offer the following answer.

In 1980 in the British department of the KGB, Orlov's file was extracted from the archives. It was a period in which all sec- tions of the KGB were busily writing the 60 years' history of Soviet intelligence. A group of officers realised that Orlov was not a traitor in the full meaning of the word. They reasoned that he had fled to the West to avoid certain death, which partly excused him, and that he had never given away the names of any Soviet high- level agents. Was this not the moment to rehabilitate him?

The question was then postponed. The KGB was not yet ready for such bold think- ing. But the time did come in 1989-91 when, under the influence of Gorbachev's glasnost, the KGB needed to start a dialogue with the public. Another factor was that defections of KGB officers had become more frequent, and some propagandistic counter-measures needed to be taken. But the last straw was the publication of KGB: The Inside Story by Christopher Andrew and myself, which the KGB took as a deliberately hostile action (though this was not in fact true). It was thus decided to carry out an 'active measure': the publication in the West of a book about a defector who remained loyal to the KGB. At the same time the KGB wanted to advertise itself and boast to the world about the exploits of Soviet intelli- gence in the 1930s, when it achieved such outstanding success against this country.

Oleg Tsarev, whom I know well, was appointed by the KGB to carry out the operation. He used to be my subordinate in the British department. In 1974-79 he spied against Britain under the cover of a Lon- don correspondent for the newspaper Socialist Industry. It was a clever decision. Tsarev, by KGB standards, is an intelligent and liberal person. Furthermore, he is an anglophile: he adores everything British and even in his appearance and manner- isms apes the English gentleman. But, with all his ability, he is not a writer. He needed a Western collaborator, and found one in John Costello.

During the launch of Andrew's and my book in 1990, Costello made a rowdy and hysterical scene protesting about the 'hype'

connected with it. According to some rumours, Costello behaved in this manner to attract the attention of the KGB, whose people were present. It worked. Shortly afterwards the KGB offered him the col- laboration with Tsarev, which he gladly accepted.

The product of this symbiosis clearly carries the stamp of the not entirely coinciding interests of Costello and the KGB (apart from a mutual desire to embarrass the American and British gov- ernments). Costello, trying to satisfy Moscow, tells the long and often dreary story of Orlov's adventures. Deluging his readers with insignificant detail, he appears at times to be writing not for the general public but for the handful of those espi- onage freaks in Europe and America who watch each other's work with burning jeal- ousy. The chapters about operations in Germany and France look like attempts to popularise the book in those countries. But when he is free from such promotional and financial dictates, his ability as an enthusi- astic historian prevails, and his narrative is vivid and captivating.

Costello cleverly exploited the KGB's desire to find channels to the international publishing world, extracting, with Tsarev as his medium, document after document from the KGB files. With their help, he compiled by far the best version hitherto of the history of the recruitment and the first four to five years of activity of Philby, Maclean and Burgess. There are fascinat- ing details here, such as how much the three agents were paid compared with KGB officers themselves (in 1935 Philby was paid ┬Ż11 monthly, Maclean, ┬Ż10, and Burgess, because of his extravagant lifestyle, ┬Ż12. 10s. Orlov's salary was ┬Ż120); exactly which British secrets they passed to Moscow (Costello alleges that Maclean, apart from being the first British source on the development of nuclear weapons, sent the KGB instructions issued by the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, as well as information helping the Soviets to decrypt the British cipher systems); and that Burgess was used as a homosexual lure to compromise MI6 officers.

Doubtless under pressure from Tsarev, Costello seems to overstress the role of Orlov, who was briefly posted to Britain in the mid-Thirties, in the recruitment of the Cambridge spies. But it clearly emerges from his text that the men who laid the foundation of the Soviet network in Britain in the 1930s were three brilliant Soviet agents: the Austrian Marxist intellectual, Arnold Deutsch; a former Catholic Hun- garian priest turned communist, Theodor Maly; and the industrious Russian acting head of the KGB station in London at that time, Ignaty Reif. Cosmopolitan, eloquent and driven by idealism, these three left an indelible impression on their recruits, turn- ing them into Soviet spies for life. But, as correctly perceived by Costello, they were not really representative of what Soviet communism came to be. He continues:

All the spymasters, with the exception of Deutsch [who died during the second world war], were soon to he liquidated, imprisoned or forced to flee like Orlov from a totalitari- an tyrant's mindless and self-aggrandising brutality.

The next-generation KGB officers were mostly narrow-minded, cynical, cowardly and uncouth, but the Cambridge and other British traitors had to put up with them.

The effect of this book is equivocal. The KGB had wanted to project the image of Orlov as a dedicated intelligence officer who remained faithful to his Chekist obli- gations under difficult conditions ŌĆö an unusual kind of hero. But we ourselves see an obnoxious character, who started tortur- ing and killing in Poland in 1920 and con- tinued to do so in Spain in 1937-38 (one of his direct victims was head of POUM Andres Nin), corrupting Western society with espionage, deceiving the American and British governments for 20 years, thus continuing to damage Western nations.

The KGB wanted to tell us about their outstanding achievements. In fact, we read an interminable story of deception, corrup- tion, secret denunciation, assassination and perfidy ŌĆö all features of the Soviet system, and particularly of its main product, the KGB.

John Costello's and Oleg Tsarev's clear objective was to annoy the American and British governments. (The promoters of the book even make the absurd claim that 'British diplomats in Moscow have appealed to the Russian Intelligence Ser- vice . . to curtail its co-operation with Costello'.) In fact there is absolutely noth- ing in the book which can seriously disturb the peace of mind of anyone on either side of the Atlantic. Any embarrassment has turned out to be an illusion, though not a deadly one.

'Heil Honey, I'm home.'

Previous page

Previous page