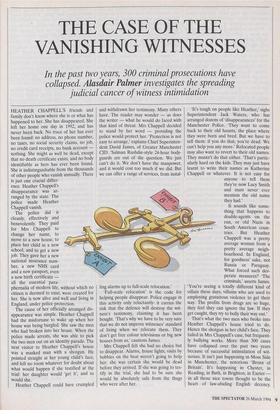

THE CASE OF THE VANISHING WITNESSES

In the past two years, 300 criminal prosecutions have judicial cancer of witness intimidation

HEATHER CHAPPELL'S friends and family don't know where she is or what has happened to her. She has disappeared. She left her home one day in 1992, and has never been back. No trace of her has ever been found: no address, no phone number, no taxes, no social security claims, no job, no credit card receipts, no bank account — nothing. She might as well be dead, except that no death certificate exists, and no body identifiable as hers has ever been found. She is indistinguishable from the thousands of other people who vanish annually. There is just one crucial differ- ence. Heather Chappell's disappearance was ar- ranged by the state. The police made Heather Chappell vanish.

The cause of her officially arranged dis- appearance was simple. Heather Chappell had the misfortune to wake up when her house was being burgled. She saw the men who had broken into her house. When the police made arrests, she was able to pick the two men out on an identity parade. The next visitor to Heather Chappell's house was a masked man with a shotgun. He pointed straight at her young child's face, and left no room whatever for doubt about what would happen if she testified at the trial: her daughter would 'get it', and so would she.

Heather Chappell could have crumpled and withdrawn her testimony. Many others have. The reader may wonder — as does the writer — what he would do faced with that kind of threat. Mrs Chappell decided to stand by her word — providing the police would protect her. 'Protection is not easy to arrange,' explains Chief Superinten- dent David James, of Greater Manchester CID. `Salman Rushdie-style 24-hour body- guards are out of the question. We just can't do it. We don't have the manpower, and it would cost too much if we did. But we can offer a range of services, from instal- ling alarms up to full-scale relocation.'

Tull-scale relocation' is the code for helping people disappear. Police engage in this activity only reluctantly: it carries the risk that the defence will destroy the wit- ness's testimony, claiming it has been bought. 'That's why we have to be very sure that we do not improve witnesses' standard of living when we relocate them. They don't get free colour televisions or big new houses from us,' cautions James.

Mrs Chappell felt she had no choice but to disappear. Alarms, house lights, visits by bobbies on the beat weren't going to help her: she was certain she, would be dead before they arrived. If she was going to tes- tify in the trial, she had to be sure she would be absolutely safe from the thugs who were after her. 'It's tough on people like Heather,' sighs Superintendent Jack Waters, who has arranged dozens of 'disappearances' for the Manchester Police. 'They want to come back to their old haunts, the place where they were born and bred. But we have to tell them: if you do that, you're dead. We can't help you any more.' Relocated people may also want to revert to their old names. They mustn't do that either. 'That's partic- ularly hard on the kids. They may just have learnt to write their names as Katherine Chappell or whatever. It is not easy for anyone to tell them they're now Lucy Smith and must never ever mention the old name they had.'

That's what the two men who broke into Heather Chappell's house tried to do. Hence the shotgun in her child's face. They failed in Mrs Chappell's case, but frequent- ly bullying works. More than 300 cases have collapsed over the past two years because of successful intimidation of wit- nesses. It isn't just happening in Moss Side in Manchester, the notorious 'Bronx of Britain'. It's happening in Chester, in Reading, in Bath, in Brighton, in Exeter — in all those nice towns thought to be the heart of law-abiding English decency. They're all starting to be infiltrated by drug suppliers and drug users. And that means organised crime, organised violence — and witness intimidation.

Witness intimidation is rising because it has been a spectacularly successful tech- nique. Several senior judges have voiced their deep concerns privately to me. 'I have seen a man appear twice within the last six months in the dock on charges of murder and attempted murder,' whispered one. 'Both times he walked free, because the critical witnesses were persuaded not to turn up. Each time, the man in question gave two fingers to the police, then swag- gered out of the court room grinning like a Cheshire cat. When they watch that kind of thing, it is not surprising the police feel frustrated.'

And they often do. Henry McMasters was attacked in Manchester last year by men wielding axes. He very nearly died of his wounds. But he could remember clearly the identity of his attackers, and gave the police statements to that effect. The police thought they had an unanswerable case against his assailants, who were notorious drug barons. But McMasters was persuad- ed to change his testimony. When it came to cross-examination in court, he couldn't remember anything. He even claimed, absurdly, that his wounds had been the result of a car accident. The men accused of the axing walked free.

Then there was the case of John White, who, walking home one night, saw two armed robbers shoot a security guard dead at point-blank range. He was threatened, but he decided to do the decent, responsi- ble, citizenly thing: he stuck to his story. His statement was duly shown to the defence, along with his address. A few days before he was due to testify in court, two men broke into his house in Bolton, broke both his legs and gave him injuries which required more than 20 stitches in his head.

The experience persuaded White that the decent, responsible, citizenly thing to do was not the remotely sensible thing to do. He decided not to testify. He was in any case unable to turn up on the appoint- ed day in court, since he was still in hospi- tal. The defence then suggested that he had failed to turn up because he had been involved in the crime himself. The police could do nothing to counter that argument. If a witness is beaten within an inch of his life, rules governing evidence make it impossible to explain, or even suggest, the real reason why he cannot appear in court. The effect is frequently to persuade the jury that the prosecution's case has collapsed.

It is experiences like that which have convinced Chief Superintendent David James, head of Manchester's CID, that the war on crime is going to be lost unless wit- nesses can be protected. 'There was a case in Liverpool where a cab-driver was shot coming out of a pub. The man led a blame- less life — the villains were after his broth- er, who did not. But they shot him. He survived, and he and a friend who was with him identified the man who fired the shots. But then they were threatened. By the time the case reached court, they were terrified. Both of them refused to give evidence.' The case collapsed, and the man they had earlier identified as the assailant walked free. But the cab-driver and his friend got three months for contempt of court.

It seems a travesty of justice. The guilty man goes free, whilst the victim and the witness are locked up. But the iv gave Judge Mark Potter little choice but to impose a custodial sentence. If witnesses will not testify, then the whole system fails. 'True,' admits James. 'But the law's not sensible on this, is it? Which is better — getting killed or doing three months in jail? Which would you take?' he asks rhetorical- ly. I know which one I'd choose, and it isn't getting killed. 'You've just discovered why witness protection schemes are so impor- tant,' the Chief Superintendent gleefully points out.

He decided Manchester had to have a witness protection scheme because of the scale of intimidation. And if Manchester needs one, you can bet other forces do too. The statistics show that despite the publici- ty Greater Manchester's figures for serious crime are not much different from any other large urban area's.

But surprisingly, and perhaps alarmingly, Manchester's police force is the only one in the country, outside the Met, to have a wit- ness protection programme. There are no plans to introduce a nationally organised, nationally funded scheme for the protec- tion of witnesses. The closest the new Criminal Justice Bill gets to tackling the issue is the creation of a new offence of 'witness intimidation'. Policemen do not think this is going to help. 'You try proving that a man on remand has ordered a cou- ple of his cronies to go and threaten or thrash a witness,' explains David James. 'I don't think anyone's ever gone down for it.'

Though the Home Office won't admit it, the real reason for the lack of a nationally funded scheme is straightforward: cost. Moving people, and sometimes entire fami- lies, is not just difficult, it's expensive. But the economy is a false one. Acc&ding to Superintendent Jack Waters, who runs Manchester's scheme, it may cost £10,000 to move someone. But when a trial collaps- es, the state has to pick up the costs, which frequently exceed a quarter of a million pounds. And it is not difficult to see who benefits when a trial collapses because wit- nesses have been frightened into withdraw- ing or changing their testimony.

'My name is Melvyn, and I'm addicted to group therapy.' Manchester's scheme is certainly better than nothing. But, alone, it cannot consti- tute the answer to witness intimidation. 'How many people are willing to be uproot- ed, to "disappear", to lose contact with friends and family?' asks Father Philip Sumner, a Manchester priest who knows many ordinary citizens who have witnessed crimes and then been threatened. 'You have to be very committed to want to pay that price for giving evidence which may not even lead to a conviction, and few peo- ple are. But unless we can persuade ordi- nary folk to testify, we're going to lose the war on crime.'

What becomes of the 'ordinary witness' who sees a serious crime, makes a state- ment and then finds himself and his family threatened? He can't or won't be relocated. What can the police do for him? 'Nothing,' says Father Sumner grimly. 'They promise safety, but they can't deliver. I've persuad- ed people to testify, only to have them come to me later saying that they're being threatened and the police have told them: tough, now the trial's over there's nothing we can do.' Superintendent Waters respect- fully disagrees. 'We tell them the truth: we can provide them with various levels of help, up to and including complete reloca- tion.' Sumner maintains that a 'significant proportion' of witnesses feel badly let down by the police over protection which they think was promised but never materialises. 'I've just been with a family whose reaction to helping the police is: never again. It's not worth it. They've had their house van- dalised, their kids attacked, and their own lives have been threatened. You can see their point, can't you?' Relocation is not and cannot be the solu- tion for many ordinary citizens who are wit- ness to crimes. The police favour allowing key witnesses who face intimidation to tes- tify with total anonymity. That's anathema to defence lawyers, and not too popular with judges, sympathetic though they are to witnesses' needs. It is a basic principle of English criminal law that the accused must be able to know the identity of his accusers. Without that, the ability to present an effective defence will be seriously dam- aged. According to Judge Mark Potter, 'Witnesses protected by anonymity could invent all kinds of tales. It is especially dan- gerous where identification is in question. They might have grudges against the accused which would easily be exposed if he knew who they were.' There is a fundamental issue at stake here. The right of the accused to all infor- mation which might help him establish his innocence is essential to our conception both of a fair trial and of a free society. Anonymous accusations and unidentified witnesses summon up the apparition of a totalitarian state, of show trials. If provid- ing information to the defence on the iden- tity of the witness merely ensures that the law is impotent, how can it be consistent with fairness or with freedom?

Anonymous witnesses are, of course, accepted in Northern Ireland as the only way of prosecuting terrorists successfully. The ominous question raised by the grow- ing frequency of witness intimidation on the mainland is: will the routine use of anonymity soon become the only way to deal with the terror generated by organised crime here? Many policemen, and some judges, believe the answer is yes. As drug barons extend their control further and fur- ther, intimidating more and more people, the only way to preserve the rule of law is going to be to change our views about what a fair trial involves.

It has not yet come to that. The police tell me that while threats against witnesses are often made, they are only rarely carried out. But I'm not sure I would like to have to test the truth of that proposition. To be witness to a serious crime still sounds a dis- tinctly unappealing prospect. I hope it doesn't happen to me. I want to see justice done, but don't feel ready to disappear — at least not yet.

Previous page

Previous page