Profile

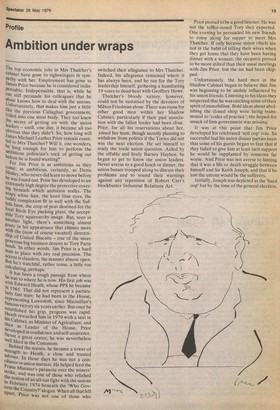

Ambition under wraps

The top economic jobs in Mrs Thatcher's cabinet have gone to rightwingers in sympathy with her. Employment has gone to James Prior because he is considered indispensable. Indispensable, that is, while he can still persuade his colleagues that he alone knows how to deal with the unions. Unfortunately, that makes him just a little like the previous Callaghan government, rolled into one stout body. They too knew the secret of getting on with the union leaders — until, one day, it became all too Obvious that they didn't. So, how long will James Michael Leathes Prior remain essen tial to Mrs Thatcher? Will it, one wonders, be long enough for him to perform the ambitious politician's trick of getting out before he is found wanting? For Jim Prior is as ambitious as they come: as ambitious, certainly, as Denis „Healey, who never did learn to move before ne was found out. Prior has developed to an extremely high degree the protective covering beneath which ambition stalks. The Wispy white hair, the keen blue eyes, the ruddy complexion fit in well with the Suffolk farm, the crop of peas destined for the local Birds Eye packing plant, the acceptable Tory squirearchy image. But, seen in another light, there's something almost goitty in his appearnace that chimes more With the (now of course vacated) directorship of United Biscuits — one of the more generous big business donors to Tory Party funds. In other words, Jim Prior is a hard Irian to place with any real precision. The accent is classless, the manner almost open. But he's watchful, rather tense, a little too calculating, perhaps. It has been a tough passage from where he was to where he is now. His first job was With Edward Heath, whose PPS he became in 1965. That did not represent a particularly fast start: he had been in the House, representing Lowestoft, since Macmillan's famous victory six years earlier. But once he established his grip, progress was rapid. Heath rewarded him in 1970 with a seat in his Cabinet, as Minister of Agriculture, and then as Leader of the House. Prior developed in confidence and self-assurance. Never a great orator, he was nevertheless vvell liked in the Commons. Behind the scenes, he became a tower of strength to Heath, a close and trusted adviser. In those days he was not a conciliator in union matters. He helped feed the Minister's paranoia over the miners' strike, and was one of those who relished the notion of an all-out fight with the unions in February 1974 beneath the 'Who Governs the Country?' slogan. When all that fell apart, Prior was not one of those who switched their allegiance to Mrs Thatcher. Indeed, his allegiance remained where it has always been, and he ran for the Tory leadership himself, gathering a humiliating 19 votes to dead-heat with Geoffrey Howe.

Thatcher's bloody victory, however, could not be sustained by the devotees of Milton Friedman alone. There was room for other good men within her Shadow Cabinet, particularly if their past association with the fallen leader had been close. Prior, for all his reservations about her, joined her team, though secretly planning to withdraw from politics if the Tories did not win the next election. He set himself to study the trade union question. Aided by the affable and lively Barney Hayhoe, he began to get to know the union leaders. Never averse to a good lunch or dinner, the union bosses trooped along to discuss their problems and to sound their warnings against any repetition of Robert Carr's blockbuster Industrial Relations Act. Prior proved to be a good listener. He was not the toffee-nosed Tory they expected. One evening he persuaded his new friends to come along for supper to meet Mrs Thatcher. If only because union chiefs are not in the habit of telling their wives when they get home that they have been having dinner with a woman, the occasion proved to be more stilted than their usual meetings with Jim Prior, but the ice had been chipped. Unfortunately, the hard men in the Shadow Cabinet began to believe that Jim was beginning to be unduly influenced by his union friends. Listening to his ideas they suspected that he was catching some of their spirit of immobil ism. Bold ideas about abolishing the closed shop were being transmuted to 'codes of practice'; the hoped-for smack of firm government was missing.

It was at this point that Jim Prior developed his celebrated `soft cop' role. So successful had his union dinner parties been that some of his guests began to fear that if they failed to give him at least tacit support he would be supplanted by someone far worse. And Prior was not averse to hinting that it was a life or death struggle between himself and Sir Keith Joseph, and that if he lost the unions would be the sufferers.

Initially, Joseph was depicted as the 'hard cop' but by the time of the general election, Mrs Thatcher herself seemed to have been given that role. But by then it was no longer a charade, for there is no doubt that the union excesses of last winter, as well as undoing Labour, forced Jim Prior to put far more teeth into his plans for the unions than he had originally intended.

The Prior package still fell a very long way short of the Tories' 1971 Act. Codes of practice had disappeared, however, in favour of the law. Conveniently choosing from the list of shortcomings the unions themselves had thoughtfully provided in their last-ditch Concordat with the Labour government, Prior promised legislation to compensate the victims of closed shops (but not to get rid of the closed shop itself); to outlaw secondary picketing, and perhaps secondary action of any kind; to provide state funds for strike ballots and union elections (but not to insist on such ballots being held); and, just to show who's boss, or to provide a bargaining counter that can be jettisoned, to force the unions rather than social security to pay at least some of the expenses of strikers' dependants.

It is not an easy package for the unions to swallow. It is somewhat tougher than Prior would have wished, but he can (and does) argue that they brought it upon themselves. At the same time, it is not quite so bad as it might have been. It is all ideal territory for the Prior style of ambiguity to operate in, and he has offered lots and lots of time for discussion and consultation.

Strange to say, despite all his efforts, Jim Prior is still not really trusted by the union men. Perhaps they cannot quite fathom what he is up to: one expressed his bafflement by describing the new Secretary for Employment as 'enigmatic'. And it is here that the questions begin to intrude. He will have to administer the Tory medicine, although he will sugar it with the maximum of delay. But the game, to some extent, has changed. The unions will huff and puff, but they can readily learn to live with some version of legal restraint, at least until it can be reversed by a Labour government.

But that is not really where their thoughts now lie. They feel their job is to protect their members against the economic policies of a Conservative government. Their preoccupation over the next few months will be not so much with what Jim Prior is planning, but with what Sir Keith Joseph is doing. They are ready to fight, for example, against de-nationalisation, and to match their pay claims to rises in indirect taxation.

If Prior really has an insider position with the union leaders, they will expect him to channel their views and their protests to the Cabinet. If he cannot intercede for them there, what earthly use is he to them? The `soft cop' game will soon be over.

Previous page

Previous page