THE SURRENDER OF HONG KONG

Brian Eads finds China's 'News Agency'

rapidly taking power and Britain rapidly abdicating

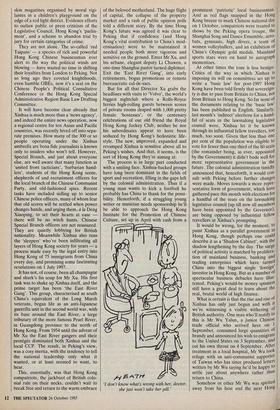

Hong Kong JUST across the road from the Royal Hong Kong Jockey Club's Happy Valley race track, about as far as a capitalist roader could throw a redundant copy of Mao Zedong's Little Red Book, stands the 24-storey, glass-fronted headquarters of Xinhua, the New China News Agency. Last season some two thousand million pounds' worth of punters' money passed through the Jockey Club's immaculately manicured hands: roughly the value of foreign loans and investments that went in through China's Open Door last year. Once upon a time, perhaps before Mrs Thatcher agreed to return the crown col- ony to Peking sovereignty in 1997, China's official representatives here might have been awed by the wealth and power of this most British of colonial institutions. Not any longer.

It isn't that the comrades are assessing the revenue possibilities of the 'double quinella', 'six up', or the 'tierce': even wily Deng Xiaoping couldn't sell that to the geriatric generals on the Central Commit- tee. It's rather that in the 12 months since the signing of the Sino-British accord on the future of Hong Kong Xinhua has transformed itself from a shadowy, some- what sinister oddity on the local scene into a major power centre on a par with not only the Jockey Club, but also the Hong- kong and Shanghai Bank, and even the governor's mansion.

Since Xinhua's director, Xu Jiatun, climbed off the train at Hung Hom railway station a little over two years ago, the previously little known first secretary of Jiangsu province has been a busy man.

To a Hong Kong that still entertained hopes of a British administrative presence beyond the expiration of the Qing dynasty lease, he looked like the familiar party cadre — ill-fitting clothes, knife and fork haircut and the vaguely menacing darkly tinted spectacles. A few weeks later, when he went walkabout in the infamous 'walled city', smouldering apprehensions caught fire. The point about the 'walled city' is that when the British Empire wrested permission to inhabit Hong Kong from the Manchus, the small enclave of salt traders was excluded: it remained autonomous and answerable only to China. Over the years it became a safe haven for lawlessness and vice — child prostitution, gambling, dope addicts, gangsters all prospered there. Not- withstanding the squalid living conditions, the message from Mr Xu was that here were Hong Kong Chinese people doing very nicely thank you without British administration and therein lay the future for Hong Kong.

At the time it seemed scarcely believable that the highest ranking Peking official ever posted to Hong Kong, a Central Committee member no less, could be so insensitive and inept. As things turned out, Mr Xu was right on the money, and Hong Kong post-1997 will be minus the British and answerable to Peking, for all that it is to be designated a 'special administrative region', with wide-ranging powers of self- rule.

The message has not been lost on the huge majority of the population who wish, or will be obliged, to stay. A visitor from Mars, Manchuria or Macclesfield even, could be forgiven for believing that Mr Xu, and not the short, softly spoken Welshman Sir Edward Youde, is governor of the colony. Supplicants nowadays head for Xinhua rather than the government secre- tariat.

And be it a smart cocktail party, a groaning banquet table, the ground- breaking ceremony for a new architectural monstrosity, or the most mundane airport farewell, it's at Mr Xu that cameras flash and the microphones lunge. Seldom a day goes by that he's not pictured fondling babies, gladhanding 'patriotic' business tycoons or offering some grinning pro- nouncement on the state of culture, bank- ing or women's rights in the territory.

For all that Mr Xu retired from the Central Committee during the recent house-cleaning Communist Party confer- ence in Peking (a move Hong Kong is told will diminish neither his status nor his influence), the hottest game in town these days is trying to second guess the 69-year- old Comrade Director. Colonial officials will deny it, but everyone else in Hong Kong believes that rather than seeking to preserve 'freedoms' the British administra- tion is attempting to reshape the place to Peking's taste. Evidence a crackdown on `pornography', which included a bonfire of skin magazines organised by moral vigi- lantes in a children's playground on the edge of a red light district. Evidence efforts to outlaw public or press criticism of the Legislative Council, Hong Kong's 'parlia- ment', and a scheme to abandon trial by jury for certain categories of crime.

• They are not alone. The so-called 'red Taipans' — a species of rich and powerful Hong Kong Chinese businessman ever alert to the way the political winds are blowing — have wasted no time in shifting their loyalties from London to Peking. Not so long ago they coveted knighthoods, even humble OBEs, now it's a seat on the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference or the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Basic Law Drafting Committee.

It will have become clear already that Xinhua is much more than a 'news agency', and indeed the entire news operation, now a regional centre for ten Asian and Pacific countries, was recently hived off into sepa- rate premises. How many of the 300 or so people operating under the Xinhua umbrella are bona fide journalists is known only to insiders who won't tell. However, Special Branch, and just about everyone else, are well aware that many function as `united front tacticians', 'barbarian hand- lers', students of the Hong Kong scene, shepherds of and recruitment officers for the local branch of the Chinese Communist Party, and old-fashioned spies. Recent tasks have included sidling up to senior Chinese police officers, many of whom fear that old scores will be settled when power changes hands, and urging them, a la Deng Xiaoping, to set their hearts at ease there will be no witch hunts. Chinese Special Branch officers are not reassured. They are quietly lobbying for British nationality. Meanwhile Xinhua also runs the 'sleepers' who've been infiltrating all layers of Hong Kong society for years — a process made easy by the legal entry into Hong Kong of 75 immigrants from China every day, and promising some fascinating revelations on 1 July 1997.

It has not, of course, been all champagne and shark's fin soup for Mr Xu. His first task was to shake up Xinhua itself, and the prime target has been 'the East River Gang'. This group, characterised as south China's equivalent of the Long March veterans, began life as an anti-Japanese guerrilla unit in the second world war, with its base around the East River, a large tributary of the more famous Pearl River, in Guangdong province to the north of Hong Kong. From 1954 until the advent of Mr Xu the East River gangers and their protégés dominated both Xinhua and the local CCP. The result, in Peking's view, was a cosy inertia, with the tendency to tell the national leadership only what it wanted, or at least seemed to want, to hear.

This, essentially, was that Hong Kong compatriots, the jackboot of British colo- nial rule on their necks, couldn't wait to break free and return to the warm embrace of the beloved motherland. The huge flight of capital, the collapse of the property market and a rash of public opinion polls told a different story. By the time Hong Kong's future was agreed it was clear to Peking that if confidence (and Hong Kong's vital contribution to China's mod- ernisation) were to be maintained it needed people both more vigorous and sensitive on the ground. Enter Mr Xu, and his urbane, elegant deputy Li Chuwen, a one-time Shanghai pastor turned diplomat. Exit the 'East River Gang', into early retirements, bogus promotions or remote bureaucratic cul-de-sacs.

But for all that Director Xu grabs the headlines with visits to 'Volvo', the world's biggest nightclub where a Rolls-Royce ferries high-rolling guests between scores of private rooms draped with 1,000 pretty female 'hostesses', or the centenary celebrations of our old friend the Royal Hong Kong Jockey Club, neither he nor his subordinates appear to have been seduced by Hong Kong's hedonistic life- style. The new, iiiiproved, expanded and revamped Xinhua is sensitive above all to Peking's wishes. And that, it seems, is the sort of Hong Kong they're aiming at.

The process is in large part conducted with a smiling face. Xinhua-backed groups have long been dominant in the fields of sport and recreation, filling in the gaps left by the colonial administration. Thus if a young man wants to kick a football he probably has China to thank for the yossi- bility. Henceforth, if a struggling young writer or musician needs sponsorship he'll be able to approach the Hong Kong Institute for the Promotion of Chinese Culture, set up in April with cash from a I don't know what's wrong with her, doctor, she just won't take her pill.' prominent 'patriotic' local businessman. And as red flags snapped in the Hong Kong breeze to mark Chinese national day on 1 October, compatriots were treated to shows by the Peking opera troupe, the Shanghai Song and Dance Ensemble,acro- bats, gymnasts, high divers, a team of women volleyballers, and an exhibition of China's Olympic gold medals. Mainland sports stars were on hand to autograph mementoes.

At other times the tone is less benign. Critics of the way in which Xinhua is imposing its will on committees set up to write a 'basic law' for post-1997 Hong Kong have been told firmly that sovereign- ty is due to pass from Britain to China, not from Britain to Hong Kong. So far none of the documents relating to the 'basic law' has been published in English. Similarly, last month's 'indirect' elections for a hand- ful of seats in the lawmaking legislative council were, Xinhua let it be known through its influential fellow travellers, too much, too soon. Given that less than one per cent of the population was eligible to vote for fewer than one third of the 80 seats (the remainder being, as ever, appointed by the Government) it didn't bode well for more representative government in the future. The colonial administration timidly announced that, henceforth, it would con- sult with Peking before further changes were made. Moves towards a more repre- sentative form of government, which have gathered pace this month with elections for a handful of the seats on the lawmaking legislative council (up till now all members have been appointed by the Governor), are being opposed by influential fellow travellers at Xinhua's prompting. It would be wrong, for the moment, to paint Xinhua as a parallel government in Hong Kong, though perhaps one could describe it as a 'Shadow Cabinet', with the shadow lengthening by the day. The surge of political activity is matched by prolifera- tion of mainland business, banking and trading enterprises which have turned, China into the biggest single `foreign' investor in Hong Kong. But as a number of spectacular business debacles have illus- trated, Peking's would-be money spinners still have a great deal to learn about the real, brutal world of high finance. What is certain is that the rise and rise of Xinhua has only just begun and with it we're witnessing a visible withering of British authority. One man who'll testify to this is Mr Wu Yalun, a junior Chinese trade official who arrived here on 1 September, consumed large quantities of brandy and announced his wish to emigrate to the United States on 3 September, and cut his own throat on 4 September. After treatment in a local hospital, Mr Wu took refuge with an anti-communist supporter of Taiwan who has since produced letters written by Mr Wu saying he'd be happy n:31 settle just about anywhere rather than return to China.

Somehow or other Mr Wu was spirited away from his host and the next Hong Kong knew he was installed at Xinhua headquarters and telling a hastily called press conference: 'I am going back home, I regret what I have done.' All the while from the Hong Kong government came a deafening silence. Mainland Chinese seek- ing asylum had best forget Hong Kong as a safe haven.

Certainly Hong Kong will have to get used to the fact that in 12 years' time China will be in the driving seat. But to more than a few people the British appear to be abdicating their responsibilities with an indecent haste, and the question is being voiced as to whether the Sino-British dec- laration on five and a half million people's future, with its solemn guarantees on maintaining the social, cultural and econo- mic freedoms until the year 2047, is really worth the paper it's printed on.

Previous page

Previous page