SHEEP MAY SAFELY GRAZE

But, as William Dalrymple

describes, the future of the Borders' hill farmers is less certain

Kelso, the Borders THEY closed the local school a few years back. Now the bus takes them away doon to the Big School.'

Alastair Murray shook his head as solemnly as if he was describing a hanging or a court-martial.

`Aye. The Big School. That's where they get a taste of the in-by — the wild life. Places like Hexham.'

We were sitting facing each other over a blue formica table-top; a battery of sauce bottles stood lined up between us. Beside Mr Murray, his face half hidden by an outsized flat cap, sat his friend, Mr Matth- ew Wood. Mr Wood was a small, lean man with fascinating fingers: bony and knotted like old olive branches. When he talked, he drummed his fingertips on the formica. The young ones like Hexham,' said Wood, a look of infinite suspicion clouding the visible portion of his face. 'They come back up here and it's all restaurant-this and disco-that. But there's nae discos in the Cheviots.'

:Aye,' said Murray. 'Away oot on the hills there's nae discos and nae much else either — 'cept yowes [ewes]. Nae shortage of them.'

`Aye. Nae shortage of them.'

That much I could vouch for. That morning I had set off from Hexham (Population: 10,000 and about as wild as a sleeping lamb) and had hitched up to the Bellingham Fair through some of the most desolate sheep country I had ever seen: a barren scape of open moorland bare but for the cold-looking flocks of Swaledales and Blue-faced Leicesters.

Bellingham is a very remote place. Coming up from Hexham the soil grows thinner and the vegetation more scraggy. The farms — smaller now, thicker-walled

stand exposed on the slopes. The road rises up, fences and hedgerows disappear, and the sheep stray onto the road. The hills close in around you; the moss is boggy, fetlock-deep. The place names on the map reflect the wildness of the landscape: the Borderers seem to enjoy naming their farms and villages after murders and atrocities: what horrors could have produced names like

Deadforcauld or Foulbogskye, Blackhaggs or Scabcleuch, Drowning Dubbs, Bitch- craig or Bloody Bush?

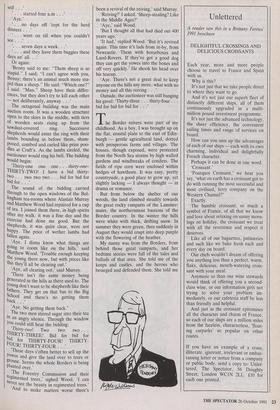

The moors up here are an unlikely place for a gathering, yet the Bellingham Fair has for more than a century been the main meeting place for the Border shepherds. These herdsmen are still — as they have always been — a breed apart, preferring the certainties of the sheep tracts to the changing ways of the 'in-by' (the areas close to the towns). They emerge only to do their shopping, perhaps once a fort- night. They mix little, unless it be with other shepherds; and that intercourse they save for two occasions in the year — the Alwinton show in the spring and the Bellingham show in early autumn.

Since my childhood I had always heard about the shows — they were the great events of the rural Borders' calendar and of the craggy old shepherds who made the journey from the most remote shielings to attend. Now as hill farming becomes an even more precarious activity, squeezed by low prices and diminishing subsidies, the shepherds of the Borders are becoming fewer: there survives perhaps a tenth of the number there were in 1945. I wanted to see the fairs before they followed the working horses and ballad singers and dry-stone- wailers into extinction.

It was late afternoon by the time I finally came over the crest of a hill and saw the low stone houses of Bellingham stretched out below me. Besieging the village on all sides was an army of huge stock lorries. At the centre of the siege was an octagonal building surrounded by a maze of sheep pens. Flat-capped and tweed-suited figures stood around as if escaped from a Thomas Hardy novel: they gossipped, whistled at their collies, and poked their sheep with long ash crooks. There was a great deal of sage shaking of heads and scratching of brows. As you drew near, you could hear fragments of conversation waft over the pickets: `Aye, I remember when we used to get a pound a week to keep my dog and my- self . .

. . . started four a.m .

`Aye.'

. . .no days off 'cept for the herd dinners . .

. . . went on till when you couldn't see .

. . seven days a week. .

. . . and they have them buggies these days an' all. .

Or again: `Benny said to me: "Them sheep is so stupid." I said: "I can't agree with you, Benny; there's an animal much more stu- pid than a sheep." He said: "Which one?" I said: "Man." Sheep have their differ- ences, but they don't try to kill each other — not deliberately, anyway . .

The octagonal building was the main auction room. It was a wooden structure open to the skies in the middle, with tiers of wooden seats rising up from the sawdust-covered ring. Successive shepherds would enter the ring with their lambs bounding in before them, sham- pooed, combed and curled like prize poo- dles at Cruft's. As the lambs circled, the auctioneer would ring his bell. The bidding would begin: Thirty-one one one . . . thirty-one- THIRTY-TWO! I have a bid thirty- two . . . two two two . . . bid for bid for bid for . • •' The sound of the bidding carried through to the open windows of the Bel- lingham tea-rooms where Alastair Murray and Matthew Wood had repaired for a cup of tea. I joined them there, in high spirits after my walk: it was a fine day and the exercise had done me good. But the shepherds, it was quite clear, were not happy. The price of wether lambs had fallen again. `Aye. I dinna know what things are going to coom like on the hills,' said Matthew Wood. 'Trouble enough keeping the young there now, but with prices like this they'll all be clearing out.' Aye, all clearing oot,' said Murray. `There isn't the same money being generated in the hills as there used to. The young don't want to be shepherds like their fathers. They get on that bus to the Big School and there's no getting them back . .

`Aye. No getting them back.' The two men stirred sugar into their tea in an angry silence. Through the window You could still hear the bidding: Thirty-two! Two two two . . . THIRTY-THREE! Bid for bid for bid for THIRTY-FOUR! THIRTY- FOUR! THIRTY-FOUR . . `These days s'often better to sell up the Yowes and give the land over to trees or grouse. Seems the whole Borders is being Planted over.'

`The Forestry Commission and their regimented trees,' sighed Wood. 'I can never see the beauty in regimented trees.' And to make matters worse there's been a revival of the reiving,' said Murray. 'Raving?' I asked. 'Sheep-stealing? Like in the Middle Ages?'

`Aye,' said Wood.

'But I thought all that had died out 400 years ago.'

`It had,' replied Wood. 'But it's revived again. This time it's lads from in-by, from Newcastle. Them with horseboxes and Land-Rovers. If they've got a good dog they can get the yowes into the boxes and off very quickly.' He shook his head over his teacup.

`Aye. There's not a great deal to keep anyone on the hills any more, what with no money and all this reiving . . Outside, the auctioneer was still banging his gavel: `Thirty-three . . . thirty-four . . . bid for bid for bid for . .

The Border reivers were part of my childhood. As a boy, I was brought up on the flat, coastal plain to the east of Edin- burgh — gentle agricultural land, dotted with prosperous farms and villages. The houses, though exposed, were protected from the North Sea storms by high walled gardens and windbreaks of conifers. The fields of ripe corn were enclosed within hedges of hawthorn. It was easy, pretty countryside, a good place to grow up, yet slightly lacking — I always thought — in drama or romance.

But from below the shelter of our woods, the land climbed steadily towards the great rocky ramparts of the Lammer- muirs, the northernmost bastions of the Border country. In the winter the hills were white with thick, drifting snow. In summer they were green, then suddenly in August they would erupt into deep purple with the flowering of the heather.

My nanny was from the Borders, from behind those great ramparts, and her bedtime stories were full of the tales and ballads of that area. She told me of the keeps and castles, and the heroes who besieged and defended them. She told me of the English — according to her they were cruel, unprincipled invaders — who would periodically erupt from their south- ern plains in vast numbers, intent on burning our abbeys and towns. Best of all, she told me of the reivers, fearless Border guerrillas, who would sneak south and revenge themselves on the English by stealing their cattle and driving the beasts back to Jedburgh.

The reivers, gods among men, had wonderful names — Kinmont Willie, Neb- less Clemmie, Jock of the Park — and at night they would charge through my bed- room with their great rumbling herds of stolen steers. Sometimes I would go with them on their reives, and with them would fight the English.

Then, aged seven, my parents sent me to boarding school in England. There I gra- dually became anglicised, but I never forgot the reivers. When I was old enough I used to read about them: the stories of Archie Fire-the-Braes and the springing of Kinmont Willie from the dungeon of Car- lisle castle; of wee Jock Elliot and how he boiled alive the wicked warlock, Lord Soulis of Hermitage; of Jamie Telfer of the Fair Dodhead, and how he had caught the moss-troopers red-handed, removing his herds over the Borders back to England.

Years later, when I had disentangled the reivers from myth, they were still impress- ive figures. During June and July 1581, for example, one minor Scottish reiving clan, the Elliots of Liddesdale, raided western England and stole 274 cattle and 12 horses; they ransacked nine houses and wounded and maimed three men. Over the following eight years, the same family increased their takings to 3,000 beasts and more than £1,000 worth of goods; they destroyed 66 buildings, murdered 14 men and took 146 prisoner.

At the height of their activities, the reivers reduced the Borders to a Lebanon- like anarchy: it was said that a 16th-century resident of Redesdale would wake in the morning and first raise his fingers to his throat to ensure that it had not been slit in the night. The current revival of reiving is still on a much smaller scale. Yet wherever I went in the Borders this year, the shepherds were full of tales of raids on the most remote shielings, with the new reivers carrying off sheep and the herding buggies which shepherds use to bring their flocks in: the bikes were said to be souped up and sold off for joy-riding on the sand dunes of the Tyneside coast.

There were other tales, too, of escaped sheep wandering around the traffic islands of central Newcastle. In Cumbria, it was said, things had reached such a pass that police and farmers had co-operated in setting up a scheme called Farm Watch.

'They took the sheep and my border terrier,' I was told by Donald Dickson who runs his sheep at Johnscleuch near Dunbar in the Lammermuirs. 'They even took my 64 prize canaries.' Sheep-stealing may have driven some of them into the bankruptcy courts, but there are usually more prosaic reasons for them failing to make ends meet.

The figures are as simple as they are depressing. For hill farmers income is low; expenditure and rent are high. EEC grants, which have kept many shepherds in business for years, are now being capped. It is no longer a profitable business; and those few shepherds who remain must look after ever larger flocks of sheep.

Nor is it difficult to see why few of the shepherds' children are taking on the work. The minimum wage for shepherds this year is only £120 a week — £6,334 a year. For this the shepherd must work a seven-day week, getting only four or five hours' sleep a night during lambing time late spring — when most people are thinking of a holiday.

Moreover, the generation of shepherds' sons who headed into the towns during the Sixties have done well for themselves. In 1924, Bill Rutherford Turner left school at 141/2 and went to work as assistant shepherd at the Rookin near Otterburn; he got up at 4.30 every day and earned £20 a year. His son, a senior chartered accoun- tant in Newcastle, now earns more than that per hour. The young flee the hills and head south; the old men are left trying to make the figures balance.

And all too often the profit and loss columns simply do not work out. In- creasingly, small shepherds sell up and the land is given over to forestry. Large landowners sack the shepherds and bring in contract workers. In the old days the Scottish Borderers used to raid English I think it's time I had a company carpet.' farms. Nowadays it is the English who are evicting the Borderers.

'Aye, it's those bastard Sassenachs,' said Donald Dickson. 'There used to be hun- dreds of us shepherds up here. Then the bloody English came and now there's just the contract boys. They get the job done and take the money. There's no love in it, just cash. But that's the way the whole world is going, I suppose. Everything doing double pace, no pride in a job well done any more . .

Back at Bellingham, his gloom was echoed by Matthew Wood and Alastair Murray.

'If the children of the shepherds don't take on the work no one else can,' said Murray. 'Pay them what you like, a stock- man is born not bred. You get the odd one from the towns that understands the yowes — but it's better to have it in the blood. To do the job properly, to be able to care for the sheep, you've got to be a good kenner — to know each sheep individually, to tell one from another. And you learn that from being brought up on the hills and watching your father. You can't pick it up with book-learning.'

'It's just the old men who are left now,' said Wood, surveying the line of sauce bottles. 'Once we've gone it'll all be over.'

'Aye, all over,' echoed Murray.

- Outside the tea-room, in the ring, a new shepherd was parading his lambs in front of the auctioneer: 'Thirty thirty thirty . . . thirty-one! one one one . . . THIRTY-TWO!"

Previous page

Previous page