CLASS APART

Simon Blow recalls a strange meeting

with the novelist whom television has just made newly famous

SATURDAY'S superb BBC 2 dramatisa- tion of Henry Green's novel, Loving, took me back to my brief friendship with this melancholy and witty author shortly before his death. I first met him when I wrote a profile of him for the Guardian. But by then Henry Green (1905-74) was a recluse, never leaving his refuge in Wilton Place. He disliked being photographed and interviewed, but I guessed — correctly — that he was probably immensely flat- tered by the attention of a much younger person.

After some conversation — during which my credentials were established he agreed to the interview and photo- graph. He was intrigued by the fact that he had known my grandmother — a particu- larly fast lady who had had three husbands and five children: in brief, a bolter. He kept returning to her during the interview: she was a cousin of his. But despite his curiosity about other people, he was deter- mined that the real man, Henry Yorke, should never be known. Green lived as Henry Yorke — his true name — when he stopped writing and was anxious to keep his writing personality of Henry Green and his private personality of Henry Yorke separate. I, however, interviewed him as Henry Green or, as it turned out, he inter- viewed himself.

Yorke had a double identity because he believed a writer should be anonymous. He put this well in his autobiography, Pack My Bag:• 'Prose should be a long intimacy between strangers with no direct appeal to what both may have known. It should slow- ly appeal to feelings unexpressed, it should in the end draw tears out of the stone.' Even when writing of himself, he tried his best to remain invisible. He suggested that he play both interviewer and interviewee, and that I should take down this interview with himself. I sat in the drawing-room of his house in Wilton Place, pen at the ready, as he began to dictate.

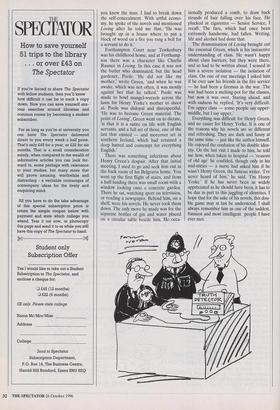

In appearance, Henry Yorke was elegantly dishevelled. He wore a double-breasted busi- ness suit that was frayed and, instead of pol- ished black shoes, a pair of floppy bedroom slippers. Instead of a shirt he wore a polo- neck sweater. As to grooming, he was unshaven and several of his teeth had dropped out. Later, his wife told me that lie quite seriously refused to go out anywhere — hence the dental decay. Nonetheless, this Knightsbridge hermit was immensely civilised and very much a gentleman.

The interview was filled with Green understatement, enigma and irony. It was done with the comedy of one of his novels. Part of the understatement was because he had dried up, and — although he did not put it like that, but rather as 'a man must stop somehow' — he was distressed that nobody, he claimed, except the Japanese, was reading him. As the interviewee, he went on to say 'that talking to someone of my generation was very hard for him to do, because after having been through two world wars, it was rather like talking to the man on the moon'. He was doubtful that books could survive, because of the vast difference between generations. He stressed that for a writer the differences were acute, and that the link between gen- erations was something that has never been properly explained, only that both had to eat, sleep, make love and, of course, die.

I wove fragments of the Green-com- posed interview into my Guardian profile. Sections, I feared, wouldn't work unless you knew the man. I had to break down the self-concealment. With artful econo- my, he spoke of the novels and mentioned Loving after he told me that, 'He was brought up in a house where to put a block of wood on a fire you rang a bell for a servant to do it.'

Forthampton Court near Tewkesbury was his childhood home, and at Forthamp- ton there was a character like Charlie Raunce in Loving. In this case it was not the butler who dominated, but the head gardener, Poole. 'He did not like my mother,' wrote Green, 'and when he was awake, which was not often, it was mostly against her that he talked.' Poole was made to bowl mangel-wurzels across the lawn for Henry Yorke's mother to shoot at. Poole was disloyal and disrespectful. `He was to become Green material. The point of Loving', Green went on to dictate, `is that it is a satire on life with English servants, and a full set of those, one of the last that existed — and moreover set in southern Ireland, which had retained a deep hatred and contempt for everything English.'

There was something infectious about Henry Green's despair. After that initial meeting, I used to go and seek him out in the back room of his Belgravia home. You went up the first flight of stairs, and from a half-landing there was small room with a window looking onto a concrete garden. There he sat, watching sport on television, or reading a newspaper. Behind him, on a shelf, were his novels. He never took them down. The only move he made was for the separate bottles of gin and water placed on a circular table beside him. He occa- sionally produced a comb, to draw back strands of hair falling over his face. He plucked at cigarettes — Senior Service, I recall. The face, which had once been extremely handsome, had fallen. Writing, life and alcohol had done that.

The dramatisation of Loving brought out the essential Green, which is his instinctive understanding of class. He wasn't happy about class barriers, but they were there, and so had to be written about. I sensed in him a severe isolation — the isolation of class. On one of our meetings I asked him if he ever saw his friends in the fire service — he had been a fireman in the war. The war had been a melting-pot for the classes, but now it was over. Staring ahead, and with sadness he replied, 'It's very difficult. I'm upper class — some people say upper- middle, but I say upper.'

Everything was difficult for Henry Green, and no easier for Henry Yorke. It is one of the reasons why his novels are so different and refreshing. They are dark and funny at the same time — just like the author himself. He enjoyed the confusion of his double iden- tity. On the last visit I made to him, he told me how, when taken to hospital — 'reasons of old age' he confided, though only in his mid-sixties — a nurse had asked him if he wasn't Henry Green, the famous writer. 'I've never heard of him,' he said. 'I'm Henry Yorke.' If he has never been as widely apprtciated as he should have been, it has to be due in part to this juggling of identities. I hope that for the sake of his novels, this dou- ble game may at last be understood. I shall always remember him as one of the saddest, funniest and most intelligent people I have ever met.

Previous page

Previous page