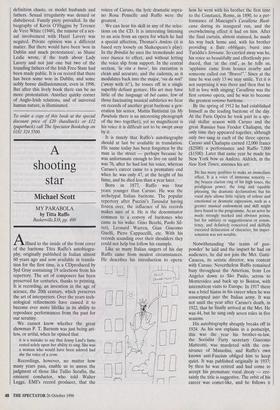

A shooting star

Michael Scott

MY PARABOLA by Titta Ruffo Baskerville,$38, pp. 490 Affixed to the inside of the front cover of the baritone Titta Ruffo's autobiogra- phy, originally published in Italian almost 60 years ago and now available in transla- tion for the first time, is a CDproduced by Syd Gray containing 19 selections from his repertory. The art of composers has been preserved for centuries, thanks to printing. It is recording, an invention in the age of science, the 20th century, which preserves the art of interpreters. Over the years tech- nological refinements have caused it to become ever more lifelike in its ability to reproduce performances from the past for our scrutiny.

We cannot know whether the great showman P. T. Barnum was just being art- less, or artful, when he opined that it is a mistake to say that Jenny Lind's fame rested solely upon her ability to sing. She was a woman who would have been adored had she the voice of a crow.

Recordings, however, no matter how many years pass, enable us to assess the judgment of those like Tullio Serafin, the eminent conductor, who told Walter Legge, EMI's record producer, that the voices of Caruso, the lyric dramatic sopra- no Rosa Ponselle and Ruffo were the greatest.

We can hear his skill in any of the selec- tions on the CD. It is interesting listening to an aria from an opera for which he had a special affection, Thomas's Amleto (it is based very loosely on Shakespeare's play). In the Brindisi he uses the tremolando and voce bianca to effect, and without letting the voice slip from support. In the central section, `la vita e breve', his execution is clean and accurate, and the cadenza, as it modulates back into the major, 'via da noi!' (`away with it!'), he tosses off in a single superbly defiant gesture. His art may have little of the language of bel canto, few of those fascinating musical subtleties we hear on records of another great baritone a gen- eration his senior, Mattia Battistini (in My Parabola there is an interesting photograph of the two together), yet so magnificent is his voice it is difficult not to be swept away by it.

It is timely that Ruffo's autobiography should at last be available in translation. His name today has been forgotten by the man in the street — perhaps because he was unfortunate enough to live on until he was 76, after he had lost his voice, whereas Caruso's career came to a premature end when he was only 47, at the height of his fame, and he died less than a year later.

Born in 1877, Ruffo was four years younger than Caruso. He was the archetypal Italian baritone. The popular repertory after Puccini's Turandot having frozen over, the influence of his records makes sure of it. He is the denominator common to a convoy of baritones who came in his wake: Gino Becchi, Paolo Sil- veri, Leonard Warren, Gian Giacomo Guelfi, Piero Cappuccilli, etc. With his records sounding over their shoulders they could not help but follow his example.

Like so many Italian singers of his day Ruffo came from modest circumstances. He describes his introduction to opera: how he went with his brother the first time to the Constanzi, Rome, in 1890, to a per- formance of Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusti- cana during its inaugural run, and the overwhelming effect it had on him. After the final curtain, almost stunned, he made his way back home and, with his brother providing a flute obbligato, burst into Turiddu's Serenata. So carried away was he, his voice so beautifully and effortlessly pro- duced, that 'at the end', as he tells us, `applause came from houses nearby and someone called out "Bravo!".' Since at the time he was only 13 we may smile. Yet it is not surprising it was there and then that he fell in love with singing; Cavalleria was the first verismo opera, and he was to become the greatest verismo baritone.

By the spring of 1912 he had established himself as the leading baritone of the day. At the Paris Opera he took part in a spe- cial stellar season with Caruso and the great Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin, the only time they appeared together, although only two sang in each of the three operas. Caruso and Chaliapin earned 12,000 francs ($2500) a performance and Ruffo 7,000 ($1500). Later that same year he made his New York bow as Amleto. Aldrich, in the New York Times, assesses his art:

He has many qualities to make an immediate effect. It is a voice of immense sonority the brazen clarion ring of his high tones, the prodigious power, the long and equable phrasing, the dramatic declamation; but his vocal style allows little variety of colour and emotional or dramatic expression, such as a greater musical endowment and skill might have found in the programme. As an actor he made strongly marked and obvious points; but for subtlety or suggestiveness or consis- tency, and definitely conceived and skilfully executed delineation of character, his imper- sonation was not notable.

Notwithstanding 'the trains of gun- powder' he laid and the impact he had on audiences, he did not join the Met. Gatti- Casazza, its artistic director, was content with Caruso. Nevertheless Ruffo remained busy throughout the Americas, from Los Angeles down to Sao Paulo, across to Montevideo and back up to Boston, with intermittent visits to Europe. In 1917 there was a brief hiatus in his career when he was conscripted into the Italian army. It was not until the year after Caruso's death, in 1922, that he finally arrived at the Met. He was 44, but he sang only seven roles in five seasons.

His autobiography abruptly breaks off in 1924. As his son explains in a postscript, this was the year his brother-in-law, the Socialist Party secretary Giacomo Matteotti, was murdered with the con- nivance of Mussolini, and Ruffo's own known anti-Fascism obliged him to keep quiet. It was published originally in 1937; by then he was retired and had come to accept his premature vocal decay — cer- tainly the title is suggestive. The orbit of his career was comet-like, and he follows it

Previous page

Previous page