ARTS

Fantasies

Peter ALkroyd

City of Women ('X', selected cinemas) Frederico Fellini doesn't have ideas, he has sensations instead. He finds extravagant or colourful images to match those sensations but, since they are so extravagant, he finds it difficult to arrange them in an interesting or appropriate order. He just goes on, it seems, until the film runs out; which, in this case, it doesn't for two-and-a-half hours.

There is even an interval, for those who find Fellini's Italianate bravura just a little hard to stomach.

City of Women opens with a train entering a tunnel; from then on, the symbols gather momentum and it's uphill all the way. Marcello Mastroianni, known as Mr Italy in the trade, plays a middle-aged businessman, Snaporaza. We see him sit ting on the train opposite a young woman. He makes a pass at her, feeling her flesh as though it were a favourite gun-dog: 'Where are you taking that ass?' He leaves the train, and follows her to an ornate hotel, established in the middle of a dark wood, only to find it filled with women. They are shouting anti-male slogans and holding impromptu theatrical events about the enslavement of housewives. At this stage, we are puzzled but not necessarily dismayed.

But what is, in fact, going on? Snaporaza is the key. Among these female libera tionists, he is portrayed as an eccentric and somewhat endearing figure, the absentminded chauvinist, stumbling around, los ing his glasses, grabbing at the air. All around him the women are shouting 'Castration!' and 'Masturbation!'. They are giving lectures to each other about phallic power and the nature of the vagina. Fellini loves moments like these, when his prurient Italian sexuality can be given a new gloss and conventional fantasies can be transmitted in a novel shape — like a pornographer coming across the literature of some new perversion.

But something else is going on, too. These women are portrayed as either ab surd or extraordinary — in other words, they lack reality. They are obviously harridans of the worst kind and, when one of them sings out: 'All women are young! All women are beautiful!', they are flying in the face of facts as well. It's clear that Fellini does not like, or does not understand, what is going on. He treats these women and their ideology as sheer theatre; as a result, they become as impersonal as puppets.

It looks, however, as if Snaporaza is going to be killed or castrated any minute — but, whenever reality intrudes too closely, Fellini always turns to fantasy as a way ot camouflaging the problems he is having with his material. And so Snaporaza Is almost raped by an old and revolting peasant woman, in a scene straight out of opera bouffe, finds himself threatened by lesbian terrorists, and attends the party of a roue celebrating his 10,000th conquest. I think at this point Fellini introduces his 10,000th character but I'm not sure. The mood of the film has changed from satire to farce and then to pantomime; the sets are clearly artificial, the melodrama contrived. As long as we willingly accept the illusion, the film drifts by happily, albeit haphazardly, enough. Fellini is, after all, at his best when he takes images from dreams or from fantasies, and lends them a claustrophobic reality — the corridors leading nowhere, the winding stairways, the fearful shadows upon walls.

But Fellini does not want to be seen merely as the technician of illusions; he has insisted that City of Women be taken seriously as a commentary upon contemporary life. It is a film about the nature and nurture of women. But it's difficult to know where to start, the women are so bewildering and various. Some of them adopt male roles; others become idealised images, like the marble bust of his mother which the roue kisses every night; others are just nymphomaniacs. In one intriguing although perhaps familiar sequence, Snaporaza regresses through the stages of his infancy and sees again the women of his boyhood — those women whose images he has both loved and betrayed, who are both too close and too far away. He talks continually in broken syllables, like a child. The shock, which comes close to destroying him, lies in his encounter with 'radical' or 'liberated' women who puncture those infantile images which he has retained. The point here, I think, is that these infantile dreams of women both misrepresent and injure real women — they are both less and more than the images which men have created. But, on the other hand, when real women fight back, they in their turn destroy the men who have for so long clung to the stereotype.

So far, so good. And yet analysing a film by Fellini is like scrutinising a series of fairground booths for some hidden significance. City of Women is primarily a film to look at rather than look through, since his major talent lies in the presentation of the grotesque or the surreal. The trouble is that he has never stopped indulging that talent. His technique worked very well with subjects which required very little elucidation — the fashionable world of La Doke Vita and the homosexual world of Satyricon. But the staleness of his devices becomes all too evident when he deals with a theme so immediate, and still in some quarters so important, as that of sexual politics. He runs the risk here of appearing trivial, and even decadent.

Watching Fellini is, in this sense, like leafing through the latest edition of L'Uomo. It has the same attention to style — but, more importantly, the same belief that only style is important. But stylists are only interesting when they consciously choose to forego substance. Fellini can't make that choice. And, when he tries to be serious, he succeeds only in becoming meretricious. His period was really the Sixties, when his slick vision matched the image of the age. Now, I'm afraid, he seems only like an Italian Ken Russell — and, sometimes, not even as good as that.

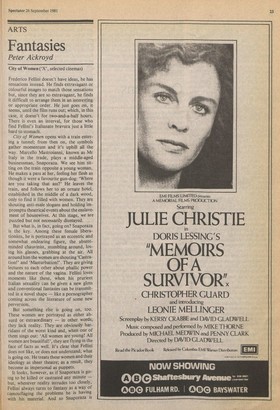

Previous page

Previous page