. . . AND LONDON

Paul Barker meets

the men who sleep out in London

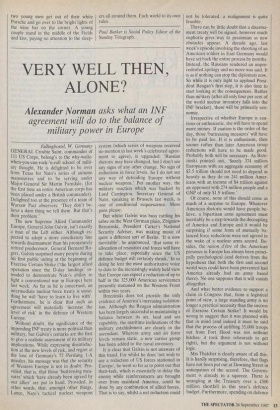

RATSO lives in what he calls, wryly, Tennis Court Boulevard in Lincoln's Inn Fields. He has big eyes and a scarred forehead. He is 36 next birthday. Like all London's sleepers-out, he is a great reader. He questions me about the Telegraph's editorial move to the Isle of Dogs.

The number of 'vagrants — the men (very few women) who sleep out rough — is growing, and they are getting younger. The old wino is no longer the right image,' I was told — though there remain plenty of old winos.

I suspect that many people think of them as an undifferentiated morass of misery. But it isn't so. Just because they have chosen, or been forced, to live unlike the rest of the world, sleepers-out have not abandoned all ideas of rules. They have their own tribal divisions, their pecking order and their own codes of morality.

Many are ex-soldiers, who learnt about rules in their military years, even if they learnt nothing else much, apart from how to prop up the Naafi bar. They are often fiercely independent. That is one reason for preferring Lincoln's Inn Fields, in the middle of London, to a hostel. There's camaraderie, if you want it.. Ratso, how- ever, says he avoids the little schools of drinkers, because they end in punch-ups.

Ratso has been 18 years in London, since he left home in Middlesbrough. He has been in and out of jail. 'I've not been in for two years now: they haven't caught me yet. I'll probably be in again. I was in last time for shoplifting. I was stupid. I got greedy. But the nick's just part of life. If you worried about it, you wouldn't commit the crime in the first place, would you? You just do your time, and think of the £61 you get when you get out.' In one Teesside philosophical side-swipe he thus de- molishes the whole theory of deterrence.

These are the rules Ratso lives by. He has his geographical routine. 'I get up in the morning, about six, and then I wander over to the day centre.' This is in a Victorian building off the Marylebone Road, with a blue plaque to the philan- thropist Emma Cons on the outside. She started it in the 1870s as a Temperance coffee house. Now it is presided over with amiable firmness by Derek White. He breaks off from time to time to don Anglican white damask silk as curate of St Cyprian's, Clarence Gate.

From the day centre, Ratso goes to 'the Dripping Factory', off Holborn. It's a church. 'If you ring the bell, they'll give you a sandwich. It was bread and dripping in the old days. Then I go back to the Fields. In this weather you can't get bedded down before eight or nine be- cause of the tennis.'

Ratso is very chirpy, very knowing. But he will then slide off into a self-protective silence. Derek White banned him from the centre for eight years because he punched him to the ground. All the sleepers-out have a high mental fence round them. They only want other people to come so far. Many were brought up in care. The break-up of a marriage or the loss of a job precipitated them here. 'Forming rela- tionships is the problem for them,' Derek White thinks, and not (say) drink. 'Being loved is something you have to learn — at a very early age. There's no substitute for a family.'

In the evening sunlight, the Fields look idyllic. Lawyers hurry to and fro with late briefs. A dozen young and youngish women play netball. But quickly the Fields are gathering themselves together for night-time.

Men drift into the ungated Fields. Friends joke together in Glasgow or Kerry accents. It is an open-air version of the old-style 'public bar', which pubs almost everywhere have merged into the 'saloon' or turned into a cocktail lounge.

Plastic sheets appear, draped down from sheds. They look like a moth chrysalis. Within each is a sleeping bag and a snore. Huge DIY cardboard double-cubes are balanced on the park benches. If you could not see the tremble of a sleeper inside, you would think it was the tidying-up of corpses after Hiroshima. Over by the tennis courts, some latecomers are still constructing their overnight coffins. They build them punc- tiliously. I am reminded of soldiers squar- ing off their blankets for barrack-room inspection.

At the day centre, a list gives 21 regular sources of free food. 'Nobody starves in London,' Ratso says. 'There's too many handouts. And it's surprising what you can get in a litter bin. Tourists, especially, throw things away. Not bad, is it?' • Surprisingly many sleepers-out have a watch. If you thought that time did not matter, you would be wrong. Many have a radio or a Walkman. Ratso has a little yellow 'wireless'. He likes LBC and Radio Four. Like newspaper-reading, radio- listening is an agreeable cocoon.

`I don't look bad, do I?' Ratso says. And he doesn't. Many sleepers-out -- if you saw them walking about — would look like building labourers going home from work. Shabby, but neat. The catch is that there isn't much labouring work left building sites anywhere, and in central London none.

I didn't see a single black or brown va- grant in my wanderings. There must be some. But generally sleeping-out is for poor whites.

Myths get wrapped around vagrants, as they do about Australian Aboriginals. They are invisible, most of the time, watching us, living by an older set of rules. When we notice them, we think they must have some secret. Are they gents down on their luck? Do they have hoards of gold? Sometimes. But you never know till they are found dead. For most of them, £100 in cash would be extreme wealth. This is less than the average take-home pay for a manual worker.

Fred Thrussell says it is not safe to have even £30 or £40 in your pocket in the Fields. 'They'll come at night and cut it out.' He is sitting on a bench under a hawthorn, trying to mend a radio. He is 57, and his mother is still alive up North at 94. He has stopped trying to spell his unusual name for most purposes. 'I call myself Michael Whitefield and get by like that.' There are a lot of more or less joky aliases among vagrants. When I sat in as recep- tionist at the day centre, I had to write down, unblinkingly, Jack Frost and Eamonn De Valera.

Fred has a friendly, impish face, long hair, and only one visible tooth. He came down to London in 1953. 'There was lots of work then, in the Fifties and Sixties. It was in the Seventies that the recession hit. It wasn't Mrs Thatcher's fault. It's the em- ployers put on the restrictions. I vote Labour. I'm from that class, the labouring class. But I don't know if it's in my interest. I'd like to see the Alliance get a chance.'

He is remarkably unbitter. 'I don't blame the Government. There's lots of opportunities. You can start up a business. I had lots of opportunities when I was young — oh yes.'

He comes from Leith, the port of Edin- burgh. He says he does casual work kitchen portering, furniture removal. He claims unemployment benefit (when he is not working, he tells me carefully) at Mortimer Street. He has been sleeping out for three years.

Many vagrants do not or will not, claim any state benefit at all. Alec is the classic old-timer. He used to sleep on the gratings of the Strand Palace Hotel, opposite an office I used to go to. I must have seen him every day. He has an oily overcoat in all weathers. He says almost nothing. The day centre looks after his old age pension and doles it out to him. Till they persuaded him to draw his pension, he had never claimed. The day centre's success is a mixed blessing. He now drinks more than he did.

Vagrants always know of someone be- low them. They have their own pride. The `ruralists' who live in and around the Fields think themselves a cut above the 'urban- ists' in Cardboard City, who live under the arches of the Charing Cross railway bridge and whose lodging is now at risk from Charing Cross redevelopment. Here, in Embankment Place, the warm smell of chips drifts across from the fish bar. The rattle of the suburban trains overhead is somehow consoling. You can use the huge illuminated clock on the riverside Shell- Mex Building to tell the time.

'Kipling lived round the corner in the 1890s. He would relish the scene now. Piles of garbage and packaging outside the fast-food restaurants give the sleepers their raw material. Up on the Strand, a little old woman stands talking to herself, next to her box for the night. The close-down of mental hospitals has given the street a new flood of recruits.

Jimmy has the cheerful, child-like face of `Our Willie' from the Scottish comic strip. His yellow sweatshirt is labelled 'All American Wrangler'. He has a flat from a nousing association. But he only goes back a couple of nights a week to clean himself up. 'Otherwise I sleep rough.'

He trembles with DTs. 'I'm a very hard drinker. I'll drink anything,' he says, in a serious Dundee voice. 'I was at the old Spike at Camberwell. I had three bottles of aftershave and a bucket. I went out and got some hair lacquer. I put it all in the bucket and I drank it. I was staggering about, bumping into walls. I was in the sick bay for three weeks.

`I don't know why I'm still alive. Lots are dead. There's only two reasons why people are on the street – alcohol and gambling. Alcoholism and perhaps drugs. I'm an alcoholic.

He says he went on the booze when his marriage in Dundee broke up. 'I'd been to college there, training as a chef. I've got two City and Guilds. It's terrible the things you see on the streets. I was in a doorway once on Old Compton Street with two mates. Just us and a lot of cardboard. We'd been drinking. They'd also been taking the tablets for alcohol. You shouldn't do both. In the morning I woke up and lifted the wine bottle and gave them a prod. I looked and they were both brown bread. I went round the corner and was sick. I'd never seen a dead body before. I went to West End Central and came back in the van. The constable was sick, too. He'd just had his breakfast.'

Jimmy sleeps where he collapses. Yogi has his own nest: a garden shelter outside a block of council flats. He looks like his old television cartoon namesake. He is chubby and brisk, with rosy cheeks and a close- cropped grey beard. Like Hemingway in his later years, too.

He has built a barricade of old mattress- es and sofas. An oil drum is a brazier for wet or cold weather. A fluffy white toy poodle is a mock watchdog. On one sofa are a bottle of pink medicine and a packet of pills. A sheet of hardboard is painted with the words, 'DHSS ponces leave me alone.'

He asks me, in broad Yorkshire, if I can see his plastic bag of belongings. I find it for him. 'They steal 'em, you know. You'll see on the bench down there. They come up this way, begging. I see 'em and give 'em summat to remember.'

He gestures behind him. 'These flats arc the worst. I remember them being built. They just take their dog for a walk, morning, dinnertime and night — and they get paid for it. They get their rent paid direct. It's this government's fault. Pay their rent all right. But you don't need to feed them.' Those are Yogi's rules.

He is 'very comfortable here — even Mrs Thatcher can't chase me off. He claims his old-age pension but nothing else.

He was a miner, from Sheffield. He came to London, doing jobs like road sweeping, when he was demobbed from the second world war. Then he put up market stalls. 'I retired from that at 74. I'm 77 now. It's easily worked out: 21 May 1910. My partner on the market stalls died at 55. It's the Special Brew that kills them off.' He makes a tippling motion with his hand, and reels off a list of the dead.

It is dark now in Lincoln's Inn Fields; two young men get out of their white Porsche and go over to the bright lights of the wine bar on the corner. A young couple stand in the middle of the Fields and kiss, paying no attention to the sleep- ers all around them. Each world to its own rules.

Paul Barker is Social Policy Editor of the Sunday Telegraph.

Previous page

Previous page