ARTS

Indian films

Demons and courtesans

Anatol Lieven urges Westerners to sample the colourful world of Indian popular cinema in a new television series Just as in the subcontinent Indian films have become the standard currency of popular culture, so here too they have done something to bind the different Asian communities together. You can see a video shop on every corner of Asian Britain, and parents encourage their children to watch films to keep up their knowledge of the old languages. To serve this audience, Channel 4 in its various seasons of Indian cinema has concentrated on showing popular clas- sics of the 1950s and 1960s, together with a few more recent smash hits like Sholay. These films are still hugely popular throughout the subcontinent and much of the Third World. Travellers' tales say that You can earn admittance to Nigerian huts and Soviet local party headquarters by whistling their songs.

Channel 4's new Sunday morning series, Movie Mahal, which began this week, consists mainly of excerpts from these films, showing the songs and dances which are so central to Indian popular cinema, together with a certain amount of introduc- tory material and interviews. In this way the directors, Nasreen Munni Kabir and Ian McAuley, hope to attract English viewers as well. I hope S9 too — and hope that anyone who takes my advice to watch won't come looking for me with a hatchet afterwards.

In the first place, timorous reader, these are not full-length films. Your stamina does not have to survive three hours of fiendishly complicated plot, full of long- lost aunts. Each episode is only half an hour long. As the film excerpts are of music and dance, you are spared the switch to realistic action and back which has the most jarring effect on Western audiences and helps to destroy the artistic unity of so much Indian cinema.

The positive case for Westerners in- terested in India to watch some at least of these programmes is that they are often very beautiful, and form a good introduc- tion to an important part of Indian culture. The film music of the 'golden age' of Indian cinema is far more accessible to Westerners than are the pure Indian clas- sical traditions, but it is also both far more rooted in tradition and simply much better than most of the Indian film music of today, which is a proper little cultural bastard if ever there was one. Three of the programmes in Movie Mahal are devoted to Naushad Ali, the most famous writer of film music, and a distinguished composer in his own right. Despite his own frequent adaptations of classical forms, he considers Indian film music to be basically a legiti- mate heir to the folk songs it has largely supplanted. In recent years, however, he

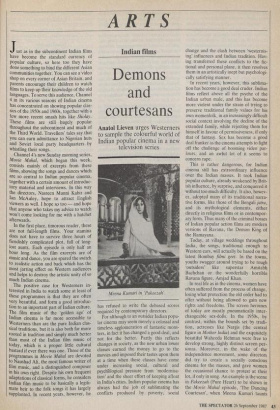

has refused to write the debased scores required by contemporary directors. For although to an outsider Indian popu- lar cinema may seem merely a colossal and timeless agglomeration of fantastic mons- ters, in fact it has changed a good deal, and not for the better. Partly this reflects changes in society, as the new urban lower classes earned the money to go to the movies and imposed their tastes upon them at a time when these classes have come under increasing social, cultural and psychological pressure from 'modernisa- tion' and the sheer effort of keeping afloat in India's cities. Indian popular cinema has always had the job of sublimating the conflicts produced by poverty, social Meena Kumari in `Pakeezah'. change and the clash between 'westernis- ing' influences and Indian tradition. Hav- ing transferred these conflicts to the fic- tional and personal plane, it then resolves them in an artistically inept but psychologi- cally satisfying manner.

In recent years, however, this sublima- tion has become a good deal cruder. Indian films reflect above all the psyche of the Indian urban male, and this has become more violent under the strain of trying to preserve traditional family values for his own womenfolk, in an increasingly difficult social context involving the decline of the extended family, while rejecting them for himself in favour of permissiveness, if only that of fantasy. Sex has become a good deal franker as the cinema attempts to fight off the challenge of booming video par- lours, and an awful lot of it seems to concern rape.

This is rather dangerous, for Indian cinema still has extraordinary influence over the Indian masses. It took Indian popular culture, already weakened by Brit- ish influence, by surprise, and conquered it without too much difficulty. It also, howev- er, adopted many of its traditional narra- tive forms, like those of the Bengali jatra, and its mythological elements, either directly in religious films or in contempor- ary form. Thus many of the criminal bosses of Indian popular action films are modern versions of Ravana, the Demon King of the Ramayana.

Today, at village weddings throughout India, the songs, traditional enough to Western ears, will actually be based on the latest Bombay filmi geet. In the towns, youths swagger around trying to be tough `outsiders' like superstar Amitabh Bachchan or the wonderfully horrible Ravana figure, Amjad Khan.

In real life as in the cinema, women have often suffered from the process of change, • losing what protection the old order had to offer without being allowed to gain new rights and freedoms. The screen heroines of today are mostly pneumatically inter- changeable sex-dolls. In the 1950s, by contrast, within the bounds set by tradi- tion, actresses like Nargis (the central figure in Mother India) and the exquisitely beautiful Waheeda Rehman were free to develop strong, highly distinct screen per- sonas. Moreover, in the wake of the independence movement, some directors did try to create a socially conscious cinema for the masses, and gave women the occasional chance to protest at their lot, if only in song. An example is the scene in Pakeezah (Pure Heart) to be shown in the Movie Mahal episode, 'The Dancing Courtesan', when Meena Kumasi taunts and reproaches her male audience in a song which has become legendary.

Apart from changing social conditions, one main reason for the decline of popular cinema since those days has been the rise of an 'art' or 'parallel' cinema (outnum- bered by about 40 to one), which has attracted directors unwilling to make the artistic and moral compromises necessary to gain a large audience within India. Satyajit Ray has been the great example, but almost as influential for younger direc- tors has been the great Marxist composer of screen epics, Ritwik Ghatak.

Why has Channel 4 not screened more of these films? Partly, the South Asian audi- ences here don't want to watch 'intellec- tual' films any more than do their Western equivalents. But also, by questioning and criticising Indian reality, such films cut straight across the established role of the cinema for the Indian masses, which is to comfort, integrate and affirm. Or, you could say, to act as an opiate. This is especially true for emigrants, who in every age have needed to look back to their homelands as a paradise lost.

However, when Channel 4 has screened Indian 'parallel' films, they have often been neither the great nor even the good ones, but the more barren and didactic productions of a misnamed 'new wave'. Their directors inhabit the same cosy Marxist Olympus as our own Tariq Ali, with its comprehensive arrogance and utter contempt for its audience and the masses it claims to serve. They call upon.the models of Brecht and Ghatak, but their pedantic and chilling formalism contains not an atom of these men's humanity or artistic genius. The result is zombie creations like Tariq's production of Manu's Partition on Channel 4 last month, which discredit Indian parallel cinema for audiences in both East and West.

It would, however, be unfair to end on such a note. Channel 4's Indian seasons have done a fine service to the South Asian communities here, which Movie Mahal continues. The series also deserves a West- ern audience looking for an introduction to a fascinating field. A word of warning, though. Avoid the programme on Pakista- ni films. The music is nice, but the colours would induce snow-blindness in a normally constructed yak.

Previous page

Previous page