ARTS

Exhibitions 1

The Art of Ancient Mexico (Hayward Gallery, till 6 December)

A feast for the art parasite

Tanya Harrod

The story is terribly involved and com- plicated even when it is not dubious,' wrote Roger Fry despondently in 1918. He had been trying to master an account of the material culture of pre-Columbian Mexico. The handsome catalogue which accompa- nies the exhibition The Art of Ancient Mex- ico at the Hayward Gallery provokes the same feeling of confusion and inadequacy. Written by a team of Mexican archaeolo- gists, it makes few concessions to the gen- eral public. Reading it is like wading through wet sand. The temptation is to give up on the tangle of Meso-American civili- sations, each with their cloudily recon- structed rituals and protean gods and goddesses.

Roger Fry and Clive Bell dealt with the problem with what now seems like imperi- alist confidence. 'If the forms of a work are significant its provenance is irrelevant,' declared Bell. 'It is the mark of great art that its appeal is universal and eternal.' However discredited this formalist approach now seems, it none the less encapsulates the way in which most of us will respond to the remarkable sculpture and ceramics at the Hayward. Indeed there is something oddly nostalgic about seeing artefacts which so clearly influenced the European avant-garde during the inter-war years. It is like going to one of the grand moment exhibitions of the period — the show of African sculpture at the Chelsea Book Club in 1920 or the remarkable exhi- bition of Chinese art held at the Royal Academy in 1935. The Art of Ancient Mex- ico is a Rolls Royce of a modern experi- ence re-presented at a time when we no longer feel so confident about some aspects of modernity.

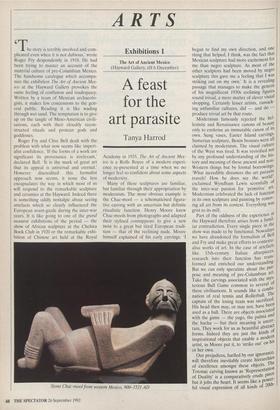

Many of these sculptures are familiar, but familiar through their appropriation by modernism. The most obvious example is the Chac-mool — a schematicised figura- tive carving with an uncertain but definite ritualistic function. Henry Moore knew Chac-mools from photographs and adapted their stylised contrapposto to give a new twist to a great but tired European tradi- tion — that of the reclining nude. Moore himself explained of his early carvings: 'I Stone Chac-mool from western Mexico, 900-1521 AD began to find my own direction, and one thing that helped, I think, was the fact that Mexican sculpture had more excitement for me than negro sculpture. As most of the other sculptors had been moved by negro sculpture this gave me a feeling that I was striking out on my own.' It is a revealing passage that manages to make the genesis of his magnificent 1930s reclining

figures sound trivial, a mere matter of clever visual shopping. Certainly lesser artists, ransack- ing unfamiliar cultures, did — and do — produce trivial art by that route. Modernism famously rejected the hel- lemstic and Renaissance canons of beauty only to enshrine an immutable canon of its own. Sung vases, Easter Island carvings, Sumerian sculpture, Benin bronzes were all claimed by modernism. The visual culture of the West was tired. It was revivified not by any profound understanding of the his- tory and meaning of these ancient and non- Western things but by formal borrowings. 'What incredible distances the art parasite travels! How he does see the world!, exclaimed Wyndham Lewis scornfully of the inter-war passion for 'primitive' art. Modernism celebrated the lack of function in its own sculpture and painting by remov- ing all art from its context. Everything was grist to its mill. Part of the oddness of the experience at the Hayward therefore arises from a famil- iar contradiction. Every single piece in the show was made to be functional. Nowadays we have abandoned the formalism of Bell and Fry and make great efforts to contextu- alise works of art. In the case of artefacts like 15th-century Italian altarpieces. research into their function has trans- formed and enriched our understanding. But we can only speculate about the por" pose and meaning of pre-Columbian art. Take the carvings associated with the mys- terious Ball Game common to several of civilisations. It sounds like a combi- nation of real tennis and Rollerball. The captain of the losing team was sacrificed. His head then may, or may not, have been used as a ball. There are objects associated with the game — the yugo, the palma and the hacha — but their meaning is uncer- tain. They work for us as beautiful abstract forms. Indeed they are just the kinds of inspirational objects that enable a modern artist, as Moore put it, to `strike out on his or her own. Our prejudices, fuelled by our ignorance, will therefore inevitably create hierarchies of excellence amongst these objects. The Totonac carving known as 'Representation of Duality' is a comparatively crude piece but it jolts the heart. It seems like a power- ful visual expression of all kinds of 20tb-

century woes — alienation, loneliness, depression, even schizophrenia. Of course we don't really know what it meant to the Totonac. Ultimately we don't really care. We are art parasites, still going strong, enjoying a quintessentially modern experi- ence.

Previous page

Previous page