THE THIRD MAN

Stephen Handelman reports on the

rise of Kazakhstan's president in what some now call the post-Gorbachev era

Alma Ata THERE is ordinarily very little to attract a traveller to the city of Alma Ata, except its name. On a grey spring day even the peaks of the Tien Shan mountains — which might otherwise offer some visual relief to the artlessly wide boulevards and blocks of flats and government buildings out of Soviet planners' copybooks — are hidden in a soupy industrial haze. Lev Trotsky, banished here in the 1920s, hated it too. The city was then just beginning to lose its charter as an exotic colonial outpost of the Tsars on the Great Silk Route to China, and was assuming the burdens of a provin- cial capital for the proletarian revolution in Moscow, 5,000 miles away. Until he con- vinced his secret police guards to let him go on hunting expeditions in the mountains, the Red Warlord, gloomily contemplating the natives who 'sat in the mud at the doorsteps of their shops . . . and searched their bodies for lice,' considered himself at the last outpost of civilisation.

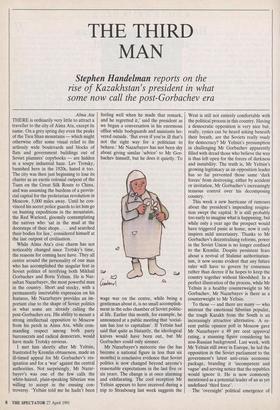

While Alma Ata's civic charm has not noticeably changed since Trotsky's time, the reasons for coming here have. They all centre around the personality of one man who has accomplished the singular feat in Soviet politics of terrifying both Mikhail Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin. He is Nur- sultan Nazarbayev, the most powerful man in the country. Short and stocky, with a permanently inscrutable expression on his features, Mr Nazarbayev provides an im- portant clue to the shape of Soviet politics in what some are already calling the post-Gorbachev era. His ability to mount a strong intellectual opposition to Moscow from his perch in Alma Ata, while com- manding respect among both party bureaucrats and radical democrats, would have made Trotsky envious.

I met him shortly after Mr Yeltsin, frustrated by Kremlin obtuseness, made an ill-timed appeal for Mr Gorbachev's res- ignation and for a 'war' against the central authorities. Not surprisingly, Mr Nazar- bayev's was one of the few calls the white-haired, plain-speaking Siberian was willing to accept in the ensuing con- troversy. `Yeltsin told me he hadn't been feeling well when he made that remark, and he regretted it,' said the president as we began a conversation in his enormous office while bodyguards and assistants ho- vered outside. `But even if you're ill that's not the right way for a politician to behave.' Mr Nazarbayev has not been shy about giving similar 'advice' to Mr Gor- bachev himself, but he does it quietly. To wage war on the centre, while being a gentleman about it, is no small accomplish- ment in the echo chamber of Soviet politic- al life. Earlier this month, for example, he announced at a public meeting that 'social- ism has lost to capitalism'. If Yeltsin had said that quite as blatantly, the ideological knives would have been out, but Mr Gorbachev could only simmer.

Mr Nazarbayev's meteoric rise (he has become a national figure in less than six months) is conclusive evidence that Soviet politics is now changed beyond anyone's reasonable expectations in the last five or six years. The change is at once alarming and exhilarating. The cool reception Mr Yeltsin appears to have received during a trip to Strasbourg last week suggests the West is still not entirely comfortable with the political process in this country. Having a democratic opposition is very nice but, really, cynics can be heard asking beneath their breath, are the Soviets really ready for democracy? Mr Yeltsin's presumption in challenging Mr Gorbachev apparently filled with dread those who believe the way is thus left open for the forces of darkness and instability. The truth is, Mr Yeltsin's growing legitimacy as an opposition leader has so far prevented those same 'dark forces' from destroying, either by accident or invitation, Mr Gorbachev's increasingly tenuous control over his decomposing country.

This week a new hurricane of rumours about the president's impending resigna- tion swept the capital. It is still probably too early to imagine what is happening, but while only a year ago the prospect would have triggered panic at home, now it only inspires mild uncertainty. Thanks to Mr Gorbachev's decentralising reforms, power in the Soviet Union is no longer confined to the Kremlin. Despite persistent fears about a revival of Stalinist authoritarian- ism, it now seems evident that any future ruler will have to govern by consensus rather than decree if he hopes to keep the country together without bloodshed. In a perfect illustration of the process, while Mr Yeltsin is a healthy counterweight to Mr Gorbachev, Mr Nazarbayev is there as a counterweight to Mr Yeltsin.

To those — and there are many — who mistrust the emotional Siberian populist, the tough Kazakh from the South is an increasingly attractive alternative. A re- cent public opinion poll in Moscow gave Mr Nazarbayev a 49 per cent approval rating, a stunning figure considering his non-Russian background. Last week, with Mr Yeltsin still away in Europe, he led the opposition in the Soviet parliament to the government's latest anti-crisis economic package, branding it 'incompetent and vague' and serving notice that the republics would ignore it. He is now commonly mentioned as a potential leader of an as yet undefined 'third force'.

The 'overnight' political emergence of Mr Nazarbayev is actually no more surpris- ing than the rise of Mr Yeltsin. As with others in his class, Mr Nazarbayev has been able to exploit the new ambiguities of power in the country. With the party patronage system of the Kremlin in tatters, the republics have become the principal strongholds of political authority, and Mr Nazarbayev's base is one of the most impressive — if only because of what he has made of it.

The republic of Kazakhstan, nearly half the size of western Europe, was for de- cades a colonial appendage of the super- ministries in Moscow. Its vast stretches of uninhabited steppeland were chosen as the site for expensive and fatal experiments in agriculture, such as the great 'Virgin Lands' scheme of the 1960s which left millions of acres depleted, as well as for more insidious purposes such as prison camps and a place of exile for Tatars, Germans and peoples deemed too subver- sive to remain in their ancestral lands in European Russia. It was also a notorious playground for the Soviet army, for whom it served as the main nuclear weapons testing area until this year. Before peres- troika, Kazakhstan was ruled tightly by a succession of Communist Party satraps who, in return for blind obedience, were given free rein to indulge their private tastes for luxury. Ironically, it was one of Mr Gorbachev's early attempts at public administration reform that finally prop- elled the Kazakhs into revolt.

The appointment of a Russian as party secretary in the republic in December 1986 sparked a riot in Alma Ata which left three dead and more than 1,000 people injured. Several of the student ringleaders were later executed. Moscow claimed at the time that the riot was instigated by the local Kazakh leadership who saw its days of nepotism coming to an end. But this first nationalist outbreak in Mr Gorbachev's Soviet Union contained the seeds of all the troubles to come. The demonstrators were since vindicated by government commis- sions which blamed the uprising on the Kremlin's stubborn refusal to relinquish any control over its far-flung empire. The lesson still has not been learned elsewhere in the country, but they seem to have taken it on board in Kazakhstan. What the rioting students were unable to achieve in 1986 Mr Nazarbayev has now accom- plished; his republic is largely in charge of its own destiny.

A senior member of the republic's gov- ernment at the time of the Alma Ata protests, Mr Nazarbayev skilfully diverted what might have been a nationalist rebel- lion into a non-racialist political one. Appointed the chairman of the Kazakhstan Communist Party in 1989, he began a quiet `perestroika' of his own aimed at giving Kazakhstan increased authority over its natural resources. Subsequently elected president by his reformed republican par- liament, he removed party control over economic management and began making plans for what is in effect the Soviet Union's most radical programme for tran- sition to a market economy. Kazakhstan citizens are among the few in the country who are entitled to buy their own flats; later this month entire sectors of state- owned property will be privatised and, over the next several years, Kazakhstan will gain control over the great mining and oil resources in its territory. Mr Nazar- bayev is no woolly democrat. Although opposition political parties exist in Kazakh- stan, they know their place. 'He says everyone is free to say what they want, but the next moment he is calling everybody into his office and persuading them there is no point in going on demonstrations', said one local politician. 'He lets you know who's boss.' It is somehow not surprising to learn that Mr Nazarbayev's models for economic development are South Korea and Singapore. 'My background is as an economist,' he says. 'I want economics to determine politics, not the other way around. That's what has gone wrong with our country.'

But Mr Nazarbayev's most important achievement has been to ensure that Kazakhstan speaks with a powerful voice in the affairs of the Soviet Union. He raised shivers in Moscow a few months ago when he floated the idea of an alliance between Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine and Byelorussia. With the Russian President Boris Yeltsin as his principal fellow con- spirator, Mr Nazarbayev suggested smoothly that if the centre could not come up with a better formula for sharing powers in a reformed Soviet confederation, then the four republics which together make up 80 per cent of the Soviet land mass would form their own union. 'Then,' Mr Nazar- bayev suggested sardonically, 'we might ask the centre to join us.' Mr Gorbachev quickly came up with a modified treaty that incorporated most of Kazakhstan's ideas for decentralising power.

Why should the Kremlin give in so readily to Kazakhstan, when similar de- mands from Russia and the Baltics bring only snarls and the threat of troops? The answer brings us to the heart of the complicated politics now being practised in the Soviet Union. Mr Nazarbayev's greatest virtue is that that he has not, like so many other radical politicians, broken his ties with the Communist Party and the nomenklatura. There are domestic pragmatic reasons; Kazakhstan along with its neighbouring Central Asian republics is still a heartland for the conservative rural party machine. But Mr Nazarbayev's firm footing inside the party structure gives him a special authority beyond the borders of his own state. Millions of moderate party members around the country, including those in senior positions in the army and the ministries, have been left without a real spokesman on the left or the right, as Mr Gorbachev increasingly retreats behind the Kremlin gates. Despite Mr Yeltsin's strength in central Russia, the Russian leader has frightened away many of those in the middle and lower levels of power who see in his populist appeal a reminder of the personality cults and chauvinism from which Russia has suffered so often in its history. It was no coincidence that Mr Gorbachev privately offered the job of vice-president to Mr Nazarbayev earlier in the year. According to one story, he decided against it after he had conducted his own pre-employment test. 'I said a few critical things just to see what would happen,' he reportedly confided later. 'Mr Gorbachev does not like criticism.'

The most telling reason for the mixture `And it's not just a suit of clothes, Your Majesty; it's a range of perfumes and toiletries as well.' of fear and respect he inspires in both Mr Gorbachev and Mr Yeltsin is the stability of his vast domain. While almost every other republic has been stricken by politic- al or ethnic unrest, Kazakhstan has been strangely quiet since 1986. The Turkic- speaking Kazakhs are now a minority in their ancestral land, making up fewer than eight million of the 16 million inhabitants of the republic. But instead of fighting each other, Kazakhs, Russians, Tatars, Ger- mans and Ukrainians are happy to make common cause against Moscow. One illus- tration of Mr Nazarbayev's unusual (for the Soviet Union) appeal across ethnic lines came this month, when he successful- ly convinced both Russian and Kazakh miners in eastern Kazakhstan to end a political strike begun in solidarity with their militant colleagues elsewhere in the country. 'He told us that it was madness to destroy Kazakhstan's economy just to make a political point in Moscow, especial- ly when he was trying himself to get exactly what we wanted,' said one admiring mine- worker in Karaganda. Yekaterina Kuznet- soya, a campaigning Kazakhstan journalist and a Russian, said simply, 'Mr Nazar- bayev is leading the whole country. That's why we follow him.' The extraordinary result of Mr Nazarbayev's politics is that in tiny, unremarkable Alma Ata one can find the same sort of exhilaration and sense of change in the air as in the Baltic republics — but without the accompanying sense of dread.

At 50, a decade younger than both Mr Gorbachev and Mr Yeltsin, Kazakhstan's president is the right age and the right generation to steer the Soviet Union safely through the 1990s. But for the moment Mr Nazarbayev abjures any national political ambitions other than the role of peacemak- er between the giants. He says he is too busy transforming his own republic. Never- theless, he is now often seen in Moscow as a prominent member of the new Federa- tion Council composed of republic leaders, and his bright corps of aides is making him increasingly available for interviews with Soviet as well as foreign journalists. He is also creating a 'think tank' in Alma Ata that points towards an intriguing future. Leading foreign academics and politicians, as well as some of the country's most impressive economists, such as Gennady Yavlinsky, author of the defeated 500-day market reform programme, have rushed to his side. His ability to maintain a high, but non-combative, profile while the rest of the Soviet Union's politicians are rhetorically gouging and kicking each other owes itself perhaps to his background as a former wrestler, a sport in which physical presence can be as intimidating as the actual use of force. By the time the man from Alma Ata enters the ring, the match may be over on points alone.

Stephen Handelman is Moscow bureau chief of the Toronto Star.

Previous page

Previous page