The mechanics of love in the Nineties

Tom Hiney

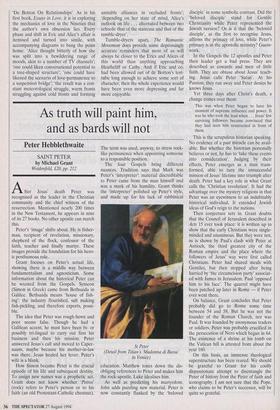

THE ROMANTIC MOVEMENT by Alain de Botton Macmillan, £14.99, pp. 326 It seems that we have more to thank Douglas Coupland for than we first imag- ined. Not only did he give us the now com- pletely redundant expression 'Generation X', but also a new format for the post-Post- modernist novel. Characterised by short chapters, regular digressions from the 'plot' and lots of ironic cartoons, `Novelisation X' eschews any story line or character-drawing in favour of presenting the author as a sociological raconteur. All of which can be fun; when Alain de Botton hits the target, The Romantic Movement is a delight to read. But when he's bad, he's awful.

Dc Botton's speciality is love and relationships, and in The Romantic Movement he gives himself what he considers an archetypal contemporary relationship to play with. Alice is 24 and in advertising. Eric is 31 and in banking. They meet at a party, go out with each other for about 12 months and then split up. They're not particularly beautiful, nor amusing, nor temperamental; in his meticulous efforts to present an 'ordinary' relationship, de Botton gets perilously close to writing a dull book. Alice and Eric operate like face- less crosses on a soccer coach's blackboard, and it is the arrows, squiggles and set-play movements between the two that interest the author.

When we meet 'Philip' (the man whom Alice will eventually turn her affections to) we get an even more thinly sketched char- acter than those we already had. On page 247, where Eric unsuspectingly introduces the couple to each other, he tells Alice that

Matt's got this friend of his, Philip. He works as a sound engineer on classical recordings. He's really nice and I remember he likes antiques, so maybe you should get along with him.

Twenty pages later, Philip is telling his friend Peter about this nice girl he's met `through Matt's flatmate Suzy'. But Suzy lives in a two-bedroomed flat with Alice; Eric has no flatmate and Matt is never heard of again.

None of this is criminal in itself, but it does help dismantle the idea that The Romantic Movement is anything other than De Botton On Relationships'. As in his first book, Essays in Love, it is in exploring the mechanics of love in the Nineties that the author's own obsession lies. Every phase and shift in Eric and Alice's affair is itemised and turned into simile, with accompanying diagrams to bang the point home: 'Alice thought bitterly of how she was split into a bewildering range of moods, akin to a number of TV channels'; `one could liken conversational potential to a tree-shaped structure'; 'one could have likened the scenario of love-permanence to a suspension bridge'; 'the result was a con- stant meteorological struggle, warm fronts struggling against cold fronts and forming

unstable alliances in occluded fronts'; `depending on her state of mind, Alice's outlook on life . . . alternated between two schools: that of the staircase and that of the tumble-dryer'.

Tumble-dryers apart, The Romantic Movement does provide some depressingly accurate reminders that most of us will always be closer to the Erics and Alices of this world than anything approaching Heathcliff or Cathy. And if Eric and co. had been allowed out of de Botton's test- tube long enough to achieve some sort of character, then the whole experience would have been even more depressing and far more enjoyable.

Previous page

Previous page